After a lull in posting, this a piece I wrote recently for the new series I’m editing over at Dark Mountain online edition. The series looks at the changing fate of the world’s oceans and how we can respond as artists, writers and feeling human beings. During the last month we’ve been exploring the beauty and the crises of the sea through fiction, art, photography, poetry and memoir. Here is my introduction from the edge of the North Sea.

‘But we love the sea!’ the woman in the back row cried. We are in the Museum of East Anglian Life at a Transition event called, What if … the sea keeps rising? I want to put my hand up and ask about the rivers. Why did the government withdraw its funds for the river defences of the Ore, the Deben, the Alde, the Blyth? But the question does not happen. There are a lot of official words going on. The woman from the Environment Agency in London is staring into her computer and talking about plans and scenarios and how some moves are less controversial than others, as we all gaze at the aerial shot of the sinuous and green waterlands of coastal Suffolk that we call home.

We love the sea. But here is climate change at our backs, warming the oceans, spoiling all our plans. Here is the tide coming in, erasing our castles in the sand. The houses that are falling down the cliffs at Easton Bavents, the disappearing cod we always took for granted with their stomachs full of microbeads, their livers full of mercury. I know, like everyone else, that something wasn’t quite right about this seaside holiday, this get-what-you-want, go-where-you-please, eat-cake-every-day holiday that lasted for a hundred years. It wasn’t all fun. It rained, you got bored and read too many books. The family quarrelled. The show on the pier was a shabby affair. And sometimes as you stood looking at the horizon, blueness all around, you felt something vital was missing.

Now in 2012, the holiday is over. I am no longer eating fish down at the harbour; I no longer cook raie au beurre noir in my frying pan, or lay wild fennel fronds underneath the flatfish from the sandbars of Sole Bay. I know too much about the boats that scour the coastlines of the world. I know why oil tankers string across the horizon like a neon necklace at night. I’ve stood with protesting communities on Walberswick beach after the floods and the threat of nuclear expansion at Sizewell. I know a lot of facts but I don’t know what to do with them.

Dragnet

In 2019, as the cruise and container ships of the pleasuredome steam ever homeward, that missing information rises like a tsunami and overwhelms us: ocean acidification, ocean current disruption, melting ice, dead zones, increasing oil spills. The bleaching of 90% of the world’s coral reefs, the disappearance of 90% of large fish, the poisoning of mangroves by shrimp farms, the destruction of sea beds for shellfish; jellyfish blooms, algae blooms, mussels cooking in their shells in California, orcas starving in Canada, seabird populations crashing in the Hebrides, whales washing up in their hundreds in New Zealand: mutilated sharks, massacred dolphins, diseased wild salmon, the last vaquita caught in a illegal net in the Bay of Cortez, bycatch of Chinese medicine makers in search of the swimbladder of the endangered totoaba. A delicacy and cure, they say, for depleted sexual potency in men.

The facts pile up as the consequences of our voracious appetites are thrown up like rotten seaweed on the shore. The bones of drowned migrants gather on the Mediterranean seabed. The lost forms of albatross chicks litter the beach in a remote island in the Pacific. People peer under the surface through television goggles, watch starfish bloom on Arctic seabeds and sharks hunt among the kelp forests of Africa. We gasp. The rainbow watery world is beautiful, savage and remote. The presence of plastic in the deep blue shocks us momentarily – but everything we touch in our terrestrial lives is covered in it. Every action in our houses, each machine we use, each product we buy from sandwich to shoe, each child that is produced, pours more toxins, more refuse, more sewage into the blue. We are tangled up in this predatory culture, like a turtle in a dragnet. Inside we flail hopelessly.

Where do we go from here?

Dark ocean

At night when the wind is in the east I can hear the North Sea heaving and sighing on the shingle, and sometimes there is a tang of salt that drifts across the marshes. It’s not a clear brochure-blue sea, it’s mostly a gunmetal grey, whose silvery shine can take you by surprise on a winter’s day. But it holds mysteries beneath its workaday exterior. The sanderlings at its edge are not a fixed territory like the country of limestone, chalk or clay.

In 1992 the writer, W.G. Sebald famously walked along this shoreline from Lowestoft to Dunwich. I sometimes sit in the Sailor’s Reading room where he once wrote, in the cold months, watched over by long-gone fishermen in sepia photographs, the model boats they crafted preserved behind glass, the clock ticking behind me. We are in a sandy place, where time shifts and unmoors you, and you can glimpse the past and future of things.

Sebald was reminded of the horrors of history as he walked along the crumbling cliffs and heathland of coastal Suffolk, the Yazidi circle we are all stuck in, doomed to repeat the cruelty of Empires. He gazed out across the German Ocean (as he called it) from Gun Hill and watched the warships of Britain and Spain battle for Sole Bay. He was always looking backwards; we are always looking forwards, equally in horror.

A fret creeps over the fields and covers the land, a lone curlew calls. Undersea, a country called Doggerland is tugging at our dreams. The men look at you with seaglass eyes out of the photographs, the men singing in the back room at the Eel’s Foot, mending the nets down at Blackshore. Without realising it, you forget which century you are in.

Long shore drift

Maybe the sea is a mood, in the way mountains are an attitude of mind, or the forest an encounter. You climb towards the summit, you slip among the trees and disappear; by the sea you let go, expand yourself to the horizon. You enter the waves and the feeling of everything changes. You emerge a different person, no longer invisible.

The sea’s mood pulls you, body and soul, into times of happiness. You can see it the way the women lie like elephant seals on the shingle, in giant nests of windbreak and thermos. In the breaking waves, the children play like sea otters. Out beyond the groynes, an old man trawls the choppy water, and emerges shaggy and dripping, invisible trident in hand. Inside we are all happy, in a way it is hard to define. Here in the great salty commons, in our half-naked creaturehood, we find ourselves level. In the streets behind the promenade, our heads are bowed, we are on a mission with shopping lists in our hands, each of us tightly defined by class and property. Here we are a colony of seals, a pod of dolphins on a hot day, calling to each other in a delight.

from ‘Triptych for Whalebone & Crabshell’ by Sharon Chin

from ‘Triptych for Whalebone & Crabshell’ by Sharon Chin

Once I dreamed that I crossed the line of death. I covered my face in ashes to fool the border guards. I saw a blue star surrounded by gold and wanted to go there – but before I left I felt myself pulled back into the deep, deep blue of the ocean and a giant crab embraced me, and it was the most powerful experience of love I have ever felt. And then she opened her claws and let me go. It was the Earth saying goodbye.

Sometimes in these summer mornings when I swim out, when I feel I cannot face the people in the streets, or any of these facts that you and I know, I let old Mother Carey embrace me, I float like a starfish on the edge of this island of rock and sand and wave. I feel the sound of the shore, the birds wheeling and clouds above me, breeze on my face. The world opens, and suddenly I am in all oceans, in all time…

So maybe this is a praise song, a shanty prose, to lull us back into a place we can share, in all oceans, in all time. We love the sea, and on a good day, a hot blue day like today, the sea loves us swimming in her, with our finny legs and our laughter.

Ultramarine

We’re always in search of a new story, of moving forward, of getting there. But what if the story we need is one we have always known but just need to remember? Not a linear narrative but a state of being, where we can hold the dark ocean as well as the light that plays on its surface, where we can weather the tsunami and still love the elements that give us life? What if what the world needs is not more facts but people with their salty bodies and souls intact, their eyes and imaginations wide open?

When you face the future there needs to be space for what the great plant metaphysician, Dale Pendell, calls a Ground State Calibration.You need to find the existential basis for all your actions that lie deep inside your being. If we don’t want a future dominated by the same feudal forces, catalogued in The Rings of Saturn, there have to be different coordinates in our ordinary lives. We have to locate another star by which to navigate, and find real kinship with this blue planet. We have to know what kind of creatures we are and what is being asked from us in return.

What if we started again here, by the sea, where the memory of our physical happiness comes to us on a summer’s day? I always thought ground state meant you needed to have your feet planted on terra firma – but what if it means being at home in another state entirely? Something more shifting and fluid. A state where we can remember our creaturehood, our place in the pod, the feeling we are beloved by the life that surrounds and holds us, its beauty and complexity?

Over the next few weeks we will be looking at our relationship with the sea and its capacity to change us, through the lens of storytellers, artists, poets and a marine biologist. We will travel from the Atlantic to the Pacific, stand on the deck of a boat, on the rocky shoreline, glide over coral and eelgrass meadows. But first, a song by Antony and the Johnsons, made for the film Chasing Extinction, and a glimpse into the lives of plankton, the miraculous lifeform that is the basis for all life in the sea and sky.

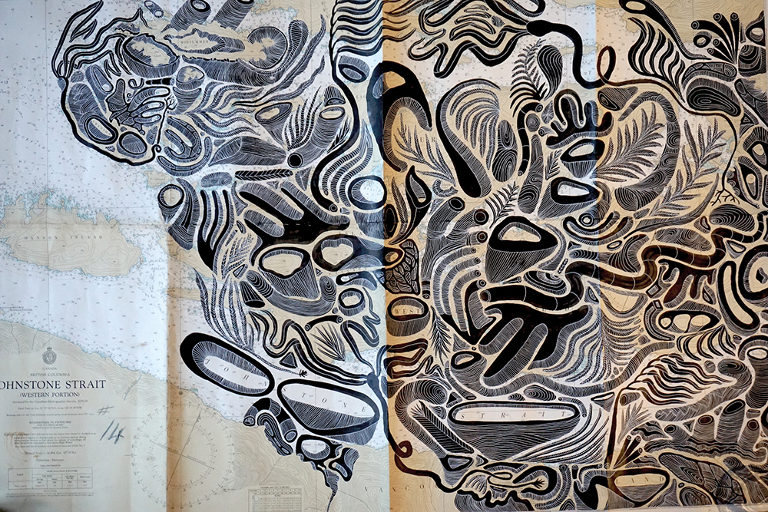

MAIN IMAGE: ‘In the Calm / In the Surge / Somewhere between Paradise and Desolation’ by Leya Tess, Ink on Nautical Chart, from the exhibition ‘We Built a Home Out of the Things We Gathered’ OR Gallery, Vancouver (Photo by Dennis Ha). Colonial place names on a nautical chart are not always very accurate. Calm Channel is anything but calm in a northwesterly. Surge Narrows can be as still as a mirror at slack tide. Published as one of the maps in Dark Mountain: Issue 14.

Leya Tess works as an artist and sea kayak expedition guide on the islands off the coast of British Columbia. Her drawing practice considers the assumed power of colonial perspectives and the fluidity of ecological cycles. leyatess.com

SECOND IMAGE: from ‘Triptych for Whalebone and Crabshell’ by Sharon Chin Watercolour and ink on paper. Illustration for a story by Zedeck Siew prompted by the plight of Rohingya people fleeing from Burma in boats in 2015. In Malay myth, the Pusat Tasek, a massive hole at the bottom of the ocean inhabited by a giant crab. When it leaves it home, it causes the rise and fall of tides. (from Dark Mountain: Issue 9).

Sharon Chin is a writer and artist working living in Port Dickson, Malaysia, She is working on a series of illustrated journalism pieces about water issues in Malaysia. sharonchin.com