“In general, I support the Christchurch shooter and his manifesto.”

That’s how the man accused of shooting at least 20 people in a Walmart in El Paso, Texas, began the document he posted on 8chan.

The atrocity comes in the wake of a murderous attack on the Chabad of Poway synagogue in California on 27 April. The man detained for that crime also posted a manifesto to 8chan and also described the Christchurch shooter as a catalyst, saying: “‘He showed me that it could be done.”

What might induce people to imitate the Christchurch massacre, an atrocity in which a self-identified fascist allegedly murdered 51 innocents in cold blood?

To answer that question, we must grasp the historical evolution of fascism in the 21st century.

The ongoing War on Terror normalised an anti-Muslim rhetoric that replicated, almost exactly, all the traditional tropes of antisemitism.

Yet, in the English-speaking world, the main beneficiaries of the new racism were not fascists but rightwing populists.

A new generation of politicians, parties and media personalities openly embraced xenophobia and Islamophobia but, for the most part, they eschewed the culture of violence associated with genuine fascists.

Racist populists denounced the “elite” for facilitating immigration. They didn’t, however, call for that elite to be executed, nor did they build paramilitary forces to physically attack those they deemed “traitors”.

Fascism grew online rather than in the real world, with neo-Nazis and white supremacists finding an audience on sites like 4chan (and later 8chan). The distinctive online troll culture allowed rants about Hitler, gas chambers and death squads to circulate widely disguised as edgy “humour”.

The election of Donald Trump, a man associated with racist populism, encouraged some fascists to move from online propaganda to real-world activism. In the United States, their efforts culminated in the Unite the Right Rally in Charlottesville in 2017, the event at which the anti-racist activist Heather Heyer was murdered.

After Charlottesville, however, most of the fascist organisations fell apart: in part because of scrutiny from authorities and the media, but mostly because of the consistent counter-protests by anti-fascists.

The Christchurch perpetrator planned his attack as a response to that defeat, and the similar decline of the Australian fascist grouplets he admired.

That’s crucial to understanding both his massacre and the killings inspired by it.

He embraced terrorism precisely because terror attacks could be launched by isolated individuals, people without organisational backing or any real political support.

Anti-fascists might prevent white supremacists from holding marches or meetings. But it was much harder to stop an unknown terrorist from opening fire in a public place.

The Christchurch killer made clear in his manifesto that his decision to murder Muslims was entirely tactical. He regarded all non-whites as “invaders” and chose Muslims simply because Islamophobia made them unpopular.

In a sense, violence was an end in itself, a way to distinguish himself from racist populists who talked but didn’t act.

It was on that basis that an Islamophobic attack could inspire the Poway shooter to shoot up a synagogue and the El Paso killer to target Hispanics, as one form of racism blended into another.

“My whole life I have been preparing for a future that currently doesn’t exist,” complains the alleged perpetrator of the Walmart massacre.

The bleakness of his manifesto, a lament about the supposed consequences of immigration and automation, echoed the grim vision presented by the Christchurch shooter, who advocated a doctrine that he called “accelerationism”.

Precisely because he didn’t believe the organised fascist right could grow in the short term, the perpetrator thought society doomed – and saw mass murder as a way of speeding up a destruction that was already coming.

His manifesto was addressed not to the public as a whole but to readers of fascist-inflected sites like 8chan. That was why he studded his manifesto with memes – even including some on the livestream of the actual murders, so that online fascists would feel a sense of ownership for the killing.

In that way he hoped to make his actions a source of fascination for damaged people whose obsession with race theory cloaked a prevailing sense of their own inadequacy and failure.

In America in particular, gun massacres have become a cultural phenomenon by which men vent all kinds of frustrations – the subsequent shooting in Ohio marked the 252nd such killing in the US in 2019 alone.

The Christchurch killer sought to politicise the familiar script associated with such events.

To the young men on 8chan, he presented gun massacre both as a political tactic and as a form of personal redemption – a way for socially awkward misfits to transform themselves into fascist supermen.

As many commentators noted, the video of the Christchurch massacre looked like a computer game. The message for other online fascists who watched the awful footage was that, by opening fire on perceived enemies, they too could become the main player and not an non-player character – even if only for a moment.

That perception was accentuated by the culture on 8chan, where self-identified Nazis discussed each new gun massacre like connoisseurs, debating the weapons tactics used and tallying up “scores” of victims.

“It’s safe to say he is ‘our guy’,” said one poster in the hours after the El Paso killings.

“Things ARE accelerating,” wrote another, “and attack are happening with increasing frequency. Hail our martyrs! Hail our heroes!”

We can only prevent future massacres if we understand the threat we face. To that end, we need an open discussion – without euphemisms and evasions – about what fascism is and how it works.

We need to distinguish genuine fascism, an ideology of violence centred on the extermination of opponents, from the rightwing populism of Trump and Fox News and Pauline Hanson.

But we also need to recognise that the normalisation of racism – by populists and others – makes the work of fascists easier.

When, for instance, Andrew Bolt says that “immigration is becoming colonisation”, his discussion of the proportion of Muslims in Lakemba and the number of Jews in North Caulfield doesn’t culminate in a call for immigrants to be killed.

Bolt is not a fascist, but his work does help popularise the “Great Replacement” theory associated with all the recent fascist terrorists, as well as providing a context in which violence against supposed “colonisers” can seem necessary.

With Donald Trump demonising American anti-fascists, it’s also important to recognise the importance of the protests that, after 2017, did so much to drive fascists off the streets.

We need more of that sentiment, not less – and we need to take it online, so as to confront the radicalisation taking place on the internet.

Most of all, we need, as a matter of urgency, to develop a positive political vision for the future.

In their manifestoes, both the Christchurch killer and the man arrested in El Paso wrote about climate change, blaming immigrants for environmental destruction.

At one level, the doctrine that the Christchurch perpetrator called “ecofascism” is obviously ridiculous. Global warming is, as the name suggests, a planetary problem: it can’t be solved by borders.

But the widespread despair about a seemingly unstoppable environmental catastrophe allows fascist accelerationism to get a hearing. If the world’s fated to burn, the notion of fanning the flames – or, indeed, becoming the fire yourself – will always find adherents.

That’s why, to counter fascist violence, we need to offer a better future, not simply more of the status quo. Confronted with the politics of hate, it’s all the more necessary to set a course on hope.

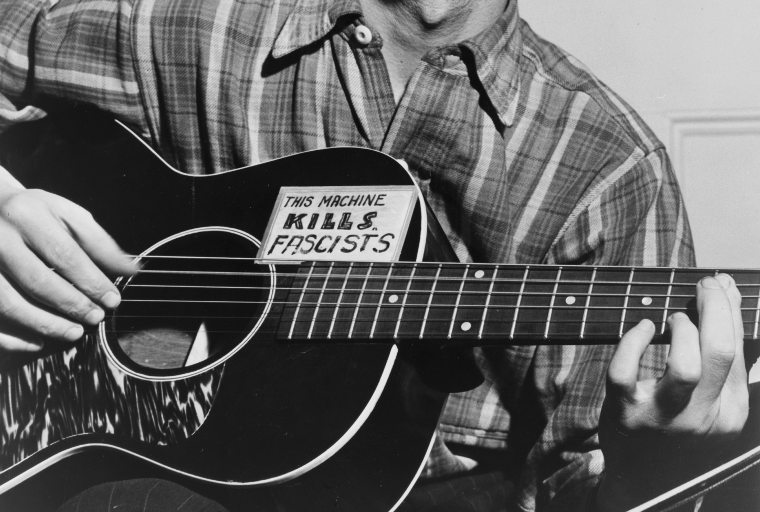

Teaser photo credit: Woody Guthrie’s guitar Public Domain