This article is the first in a four-part series on equity in public spaces. Read part two, which focuses on programming, and part three, which focuses on design.

When New York’s High Line opened in 2009, it was hailed as both a landmark in landscape architecture and a grassroots success story. The project began in 1999, when two strangers sitting next to one another at a community meeting, Joshua David and Robert Hammond, began lamenting the planned destruction of a privately-owned elevated railway in Manhattan. They mounted a successful five-year campaign to save it, and then started the design competition that would later transform it into one of the country’s most visited parks.

Crowds on the High Line. Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

But the story doesn’t end there. In the decade since it opened, prices in the neighborhood around the High Line have soared. “Starchitect” buildings sprung up along the disused rail tracks, and most recently, its northern end has been capped by the ludicrously luxurious and critically panned Hudson Yards development. Magnified by the virality of the High Line concept in other cities, the struggles of the new public space were thrust into the spotlight, prompting its creators to launch a website aimed at preventing gentrification around similar projects. New processes and programs at the High Line itself have also aimed to rectify the inequalities spurred by its popularity, but all of these efforts would without a doubt have been more effective if they were baked in from the beginning.

The High Line is only an extreme example of a common issue. What the founders hadn’t accounted for were what economists call the “externalities” of a public space. Because the places we share are so intertwined with our daily lives and with our broader urban systems, altering them can impose unforeseen costs and benefits on the community that often mirror or even exacerbate existing inequalities. Some cutting-edge public space projects, like Broadway Corridor in Portland, OR, which we have had the privilege to provide placemaking services for, or 11th Street Bridge Park in Washington, DC, have been working out new models to account for housing, workforce, educational, and social goals by combining placemaking, equitable development, and community agreements. But these projects are still few and far between.

Because these externalities are often complex and unpredictable, we at Project for Public Spaces believe that a placemaking process is the best way to address them—one that starts with broad public input and pursues implementation through a feedback loop of experimentation, evaluation, and evolution. This flexible, incremental, community-driven approach can help ensure that public space designers and managers discover and address issues of equity as they arise. But who is “the community” anyways? How do we ensure that community voices not only get heard once, but continue to be felt in a public space as it evolves? And what do we do when some voices overpower or conflict with others?

The work of making our public spaces more open and fair is hard, and you should never trust someone who claims to have all the answers to these questions. We certainly don’t, and recently we have been working hard to up our game. When it comes to equity and inclusion, we as placemakers should always strive to keep learning, both from the many skilled people who already work with local communities that are left out of traditional planning processes, and from best practices and examples around the world. Only you can do the former, but we can help with the latter.

That’s why we collaborated with Emily Manz of EMI Strategy to create a playbook for putting inclusion into action in our own work, based on recent research in the field, and now we want to share it with you. Over the next few weeks we will release it in four parts. This first week is all about broadening and deepening the community engagement process and in the next three installments, we will focus on programming, design, and management and governance.

We hope you will consider these ideas a start, not an end, in exploring how we can broaden the benefits and mitigate the costs of placemaking. Unlike theory, practice is never perfect. But in every placemaking project, we can always push to include more people, to listen more closely, to share more power, and to follow through more fully.

A COMMUNITY-POWERED PROCESS

“Effective engagement of community tops the list of crucial characteristics of successful placemaking.” —Places in the Making, MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning

At Project for Public Spaces, we often say, “The community is the expert.” In other words, ordinary people often know a great deal about what their needs are, how their public spaces work—or don’t work—and what ideas might do well in those spaces. An effective placemaking process engages these experts at the very beginning to set the priorities and vision for the project, and keeps them involved throughout implementation and beyond.

But when we are aiming to make public spaces that are truly for and by the public at large, simply turning the traditional planning process on its head is not enough. Starting with community engagement will not ensure that everyone knows about the project, let alone that they get to weigh in as much as they would like to. These four strategies can help placemakers reach out more broadly and dig more deeply with the full diversity of communities affected by a public space.

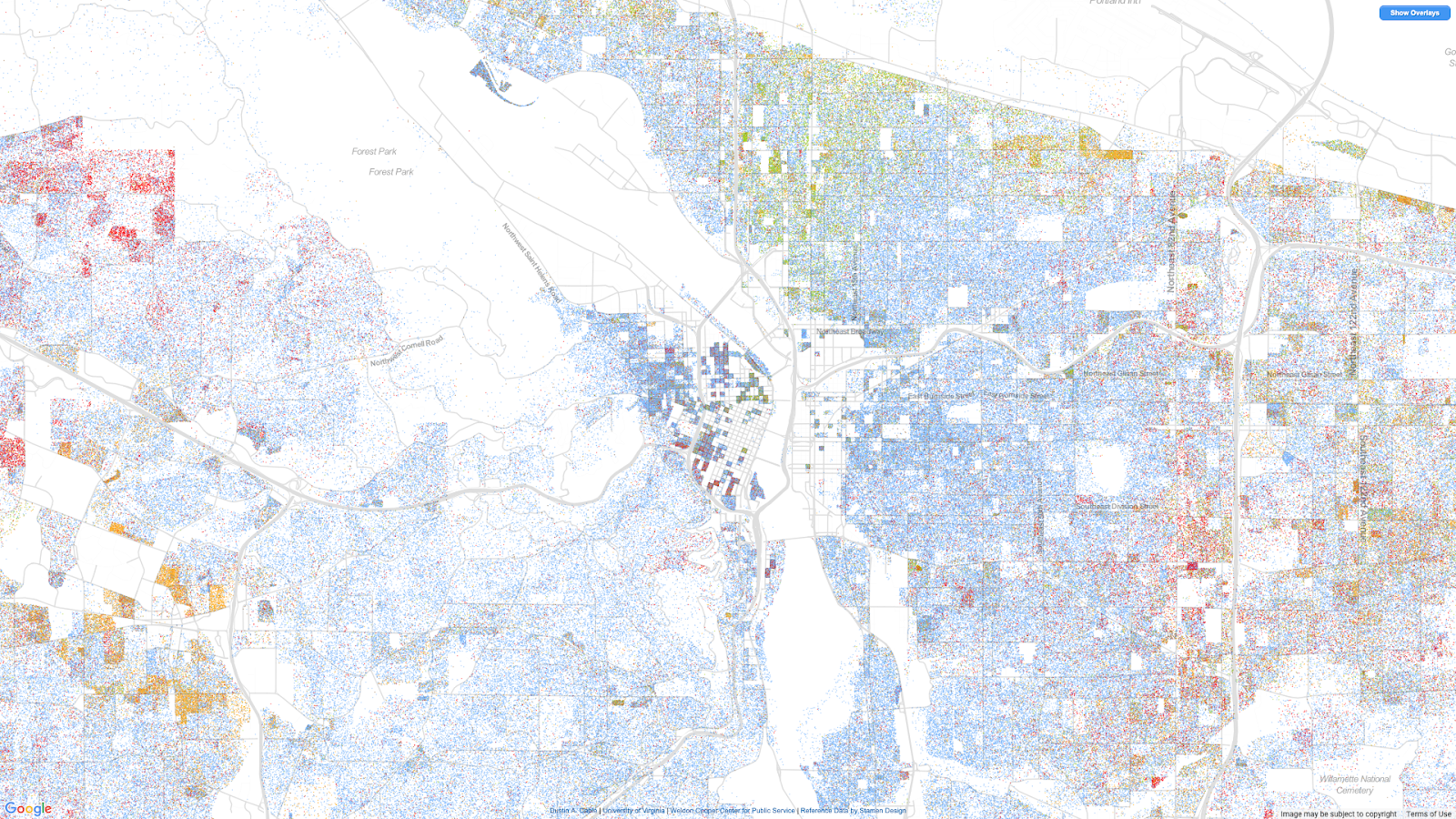

Demographic data is important context for any project. This mapping tool, which creates a visual display of Census Block data, shows White respondents as blue dots, Black respondents as green dots, Asian respondents as red dots, and Hispanic respondents as orange dots. Credit: Dustin A. Cable, University of Virginia

1. CULTIVATE CULTURAL COMPETENCY.

Cultural competency, as outlined by Julian Agyeman and Jennifer Sien Erickson, must be the basis of an equitable placemaking project. Placemaking can only ensure equitable participation if the process operates with an adequate understanding of the community: factors like age, class, and gender; issues and concerns of nearby cultural groups; language and communication; and existing power dynamics. This type of “deep knowledge” is enhanced through observation, ethnographic research, and above all, listening.

In addition to understanding how best to interact and communicate with your stakeholders, understanding the demographics of a public space’s potential catchment area can help you set benchmarks to assess whether your public process has reached an accurate cross-section of the community.

Participants in PPS’s Making It Happen training demonstrate inclusive meeting techniques, like small group conversations. Photo credit: Katherine Peinhardt/PPS

Participants in PPS’s Making It Happen training demonstrate inclusive meeting techniques, like small group conversations. Photo credit: Katherine Peinhardt/PPS

2. FACILITATE MORE INCLUSIVE MEETINGS.

Making space for everyone to contribute starts with inclusive meeting strategies, such as providing childcare, gender-neutral restrooms, interpretation and translation services, nursing rooms, and wheelchair-accessible entrances, among other considerations. And when it comes to how the meeting runs, professional facilitation and small meeting sizes can ensure more equal participation among attendees.

But even with all these considerations, simply “inviting in” diversity to a meeting does not make it inclusive. As writer and meditation guide Kelsey Blackwell writes in “Why People of Color Need Spaces Without White People,” sometimes it takes more than one meeting, by more than one group, to have all voices be heard. One common pitfall of workshops-as-usual is tokenism, where an attendee is unfairly subjected to pressure to speak for their entire community. To combat this, the placemaking process can incorporate the practice of “caucusing,” where communities of color and other frequently tokenized groups are invited to hold their own spaces before the broader group convenes.

Young people can be encouraged to lead and participate in the process of community outreach, like at this PPS workshop in Englewood, New Jersey. Photo credit: Katherine Peinhardt/PPS

3. RECOGNIZE WHEN WORKSHOPS ARE NOT ENOUGH.

Beyond workshops, outreach methods should focus on meeting community members where they are. New voices can be brought into the mix when design ideas are discussed outside of meeting rooms and made visible in everyday spaces and at cultural events. Whether that’s with an idea-gathering “lemonade stand,” or with sticker-based visual surveys posted on the side of a school bus, it is crucial to find new and creative ways to engage locals in the spaces where they feel most comfortable.

For example, transportation agencies in New Jersey have reached out to millennials using Set the Table! Civic Dinner Parties. Providing hosts with a “meeting in a box” kit designed by the Alan M. Voorhees Transportation Center Public Outreach and Engagement Team (POET), the agencies were able to gather feedback on local transportation infrastructure projects. In this case, meeting millennials in a comfortable home setting and allowing for self-directed conversations elicited new ideas that might otherwise have slipped through the cracks.

Young people can be a part of Lighter, Quicker, Cheaper public space activations, like spray-chalk bike/walk lanes. Photo credit: Katherine Peinhardt/PPS

4. FOLLOW THROUGH.

Keeping promises is one of the most powerful tools at a placemaker’s disposal to build trust with communities that have been historically wronged by urban planners, designers, developers, and policy-makers. According to a 2013 publication from MIT called Places in the Making: How placemaking builds places, “the projects that are most successful at engaging their communities are the ones that treat this engagement as an ongoing process, rather than a single required step of input or feedback.” By testing out crowdsourced ideas through Lighter, Quicker, Cheaper (LQC) experimentation, placemakers can demonstrate that they listened in good faith, keep early stakeholders involved through volunteer opportunities, and generate community buy-in as the stakes get higher throughout the project.

GET STARTED!

A public space is only as community-driven as its process. It follows that public spaces can only exist for everyone if the conversations in which they are envisioned include everyone. If we are going to do better than a status quo that reinforces existing inequalities in public space, placemaking must become a process of broad listening and deep learning—from the first workshop, through programming, design, and management.

Stay tuned for the next installment in our Playbook for Inclusive Placemaking series on programming.