LOS ANGELES — Can a big city be truly sustainable in the age of climate change? Los Angeles is trying to find out.

The United States’ second-largest city has big green plans. In April Mayor Eric Garcetti announced a goal to get 80 percent of the city’s electricity from renewable sources by 2036 and make sure 80 percent of the vehicles on the road then are carbon-emissions free.

This is part of L.A.’s version of a Green New Deal, the grand plan for decarbonization being kicked around Washington, D.C. and other localities.

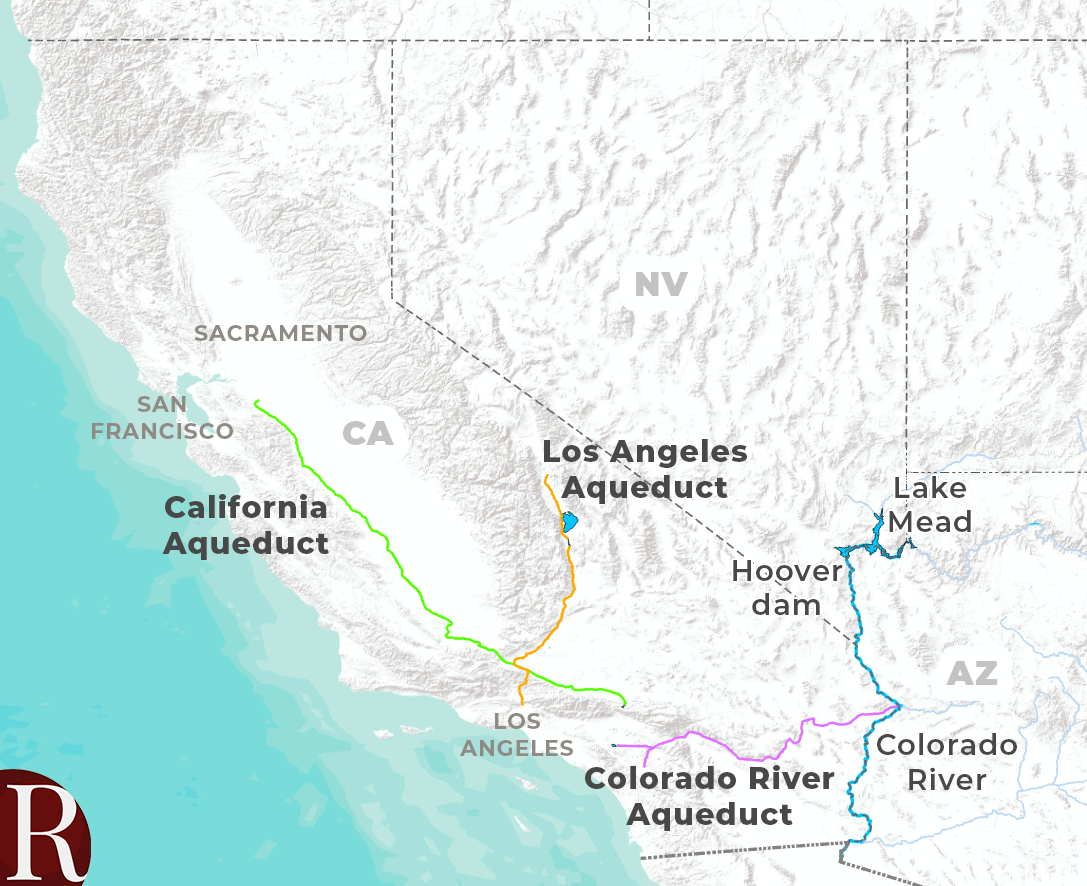

But the city’s aspirations don’t stop at clean energy. For L.A. to truly boost its climate resilience it also needs to address its water — 86 percent of which comes from three sources located hundreds of miles away. Climate change, earthquakes and other environmental pressures threaten to disrupt that supply and increase prices. With those threats in mind, the city plans to source 70 percent of its water locally by 2035 to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and build its water resilience.

“Water is our most precious resource,” says Garcetti. “Creating a more resilient, self-reliant Los Angeles means increasing the amount of water sourced locally so we can better withstand inevitable droughts and record-breaking storms — and that work starts with utilizing more innovative and sustainable water-management strategies.”

To hit its goal L.A. will need to boost captured rainwater, recycled wastewater and conservation. But the lynchpin is groundwater.

“When we talk about climate resilience and water resilience, the groundwater piece is critical,” says Cindy Montañez, chief executive officer of the nonprofit TreePeople, which works on environmental and water issues in the area. “L.A. will not be able to achieve its goal of a more local water supply and we will not be able to be a resilient city unless we look at groundwater cleanup.”

L.A. actually has lots of groundwater, but in many areas it’s simply too polluted to drink — and it has been for decades. A migrating plume of toxins in the groundwater is making more and more of the city’s wells undrinkable. Even years of remediation by Environmental Protection Agency-led Superfund projects haven’t solved the problem.

So, as the specter of climate change looms over the region, L.A. has embarked on a mission to battle the ghosts of industry past and clean up “legacy pollution” in one of the region’s main groundwater basins under the San Fernando Valley — but can it be done safely, affordably and quickly enough to help propel the city to the resilient future it seeks?

A Legacy of Hidden Wartime Pollution

The most well-known piece of L.A.’s water infrastructure is undoubtedly the concrete channel of the L.A. River, which has appeared in countless Hollywood movies and TV shows — the b-roll equivalent of the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco.

But a critical piece of the area’s water system — its groundwater — has no movie credits. For most people, it’s out of sight and out of mind.

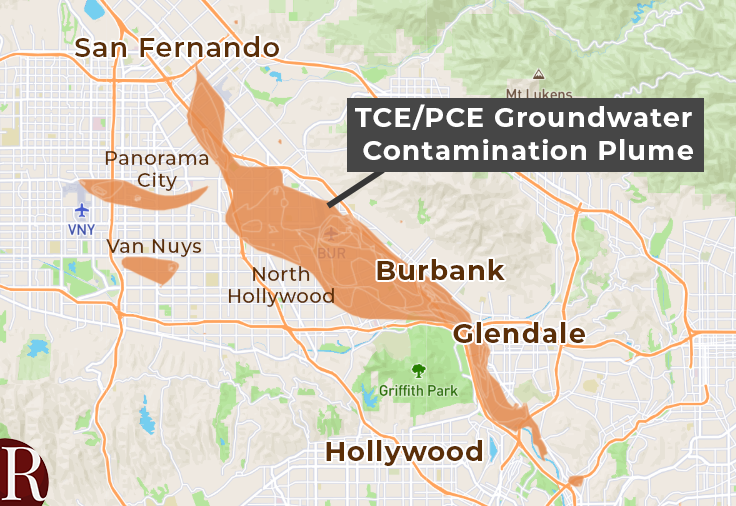

Underlying the San Fernando Valley is a large groundwater basin that could provide water for 800,000 Angelenos, but 80 percent of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power’s groundwater wells there have been impacted by contamination.

LADWP has rights to tap five groundwater basins in the region — but the vast majority of that is in the San Fernando Basin.

L.A. isn’t the only one affected. Water agencies for the neighboring cities of Burbank and Glendale also share groundwater rights to the basin, in addition to the impacts of its pollution.

Burbank today is known for its entertainment companies. It’s home to hundreds, including giants like Warner Bros and Walt Disney. Inside the walls of their studios, production companies create imaginary worlds. But back in the 1940s the city itself was a kind of set, although for a much more serious enterprise.

Disguised beneath a giant tarp, camouflaged with painted trees, homes and even fire hydrants hid a Lockheed factory. This massive facility, the size of an airport, manufactured P-38 fighter jets and other aircraft that became potent weapons in World War II. During the war years, when the factory was disguised from potential airborne spies, Lockheed and its subsidiaries in Burbank employed 80,000 people.

The war effort and the continued presence of defense companies, along with other industrial activities in the valley in the following decades, left their mark. In the 1980s volatile organic compounds such as trichloroethylene (TCE) and perchloroethylene (PCE) were found in the groundwater in concentrations that exceeded California’s safety standards.

“We have got a major problem here, and it’s got to be corrected,” Burbank mayor Michael Hastings told the Los Angeles Times in 1987. More than 30 years later, the compounds still pose problems.

Both TCE and PCE can be dangerous to human health. Exposure to TCE can cause kidney or liver cancer and can harm the central nervous system, respiratory and immune systems. It’s been linked to several cancer clusters. PCE has been classified as “likely” to be carcinogenic in humans based on tests on animals, and can also harm the central nervous, renal and digestive systems.

Once the toxins entered the groundwater, they didn’t stay put. Like food coloring dropped into a pool, a chemical plume grew under parts of Burbank, Glendale and North Hollywood.

The EPA stepped in, using the Superfund program to build groundwater-treatment systems, starting with the North Hollywood Operable Unit in Los Angeles in 1989. The Burbank Operable Unit followed in 1996, and then the Glendale Operable Unit in 2000.

Caleb Shaffer, a section chief at the EPA, calls the treatment systems successful. “They’ve treated more than 110 billion gallons of contaminated water and removed more than 175,000 pounds of contaminants from that groundwater,” he says.

But that should come with some caveats. The first is that additional industrial pollutants were detected years later, including 1,4-dioxane and cancer-causing hexavalent chromium (the latter made famous by environmental health advocate Erin Brockovich just 120 miles from L.A.).

The second is that the plume wasn’t fully contained. It’s been slowly migrating in a southeasterly direction in the groundwater basin — and that’s been bad news for LADWP.

“There’s been a number of remediation efforts over the years in the San Fernando Basin and what we found is that it simply wasn’t enough,” says William VanWagoner, who until June served as assistant director of LADWP’s water engineering and technical services division. “We were continuing to lose more and more of our wells.”

The agency started out with 115 reliable groundwater wells in the basin, but that number fell to 23 by 2018. The loss of the wells has reduced groundwater pumping by 30,000 acre-feet (about 9.7 billion gallons) a year — enough water to supply 89,000 homes.

Concerned that the number of reliable wells would continue to fall and pumping would be further diminished, LADWP took matters into its own hands.

A Plan in the Works

Shovels hit the dirt in a celebratory groundbreaking in January 2018 in the first tangible evidence of a plan to address these problems — the construction of a facility called the North Hollywood West Groundwater Treatment Project. A year later, passersby would hardly know something game-changing in the city was afoot here.

The facility is set back from the road, sandwiched between ballfields in a working-class neighborhood in North Hollywood, 18 miles from downtown L.A. This was previously known as the North Hollywood West well field, which had been taken offline years ago because of contamination. The wells are now being replumbed and two buildings are under construction that will house equipment to treat the water and manage the wells.

LADWP expects this to be one of four state-of-the-art treatment facilities that will pump contaminated groundwater, clean it up with a combination of treatment technologies and then send it into its water supply system.

North Hollywood West is planned to be operational in early 2020. Two more facilities, North Hollywood Central and Tujunga Central, have been approved by the agency’s board but neither have broken ground yet. A fourth facility, the Pollock treatment project, is still in the planning phases, but all are hoped to be completed by 2022.

“These four projects are so that we can restore our historic ability to use those well fields, while doing massive remediation at the same time,” VanWagoner told The Revelator before leaving LADWP. “We want to put them back in service and not have to wait and potentially lose even more wells in the future.”

It will likely take decades for the amount of contamination in the basin to be fully remediated, but LADWP’s plan would allow it to continue to use the water along the way. And that’s ensured by a multistep treatment process.

After sand and small particles are removed, the water is injected with hydrogen peroxide and then passed through ultraviolet reactors, which remove contaminants like 1,4-dioxane. That’s followed by granular activated carbon, which quenches the remaining hydrogen peroxide and also removes volatile organic compounds. After that, it’s ready to be added directly to the water supply.

Although granular activated carbon and UV advanced oxidation processes are commonly used for water treatment, they’re not often done at the same time.

“This is new and unique,” says Karl Linden, a professor in the environmental engineering program at the University of Colorado, Boulder and an expert in water-treatment technology. “With these two processes in combination, the system will be able to degrade all kinds of organic contaminants, including pharmaceuticals, endocrine-disrupting compounds and volatile organic contaminants,” he says.

By being able to use more of its groundwater again, the remediation facility will help to augment LADWP’s supply of local water while cutting greenhouse gas emissions — the city reports that imported water uses 3 to 4 times the energy of local water sources. It would also reduce some environmental pressure on faraway mountain sources that already face environmental pressures limiting supply and are expected to get worse. Californians rely on the Sierra Nevada’s winter accumulation for most their water supply, Angelenos included. But climate change could reduce average springtime snowpack in the Sierra by up to 64 percent by the end of the century, according to research from UCLA. L.A. also relies on Colorado River water and that basin has been mired in a two-decade-long drought.

But this new treatment technology also serves another important function — the groundwater basin acts as underground storage reservoir. “By doing the remediation and making these basins healthy and usable, that provides storage necessary for future development of stormwater and recycled water projects,” says VanWagoner.

The city has big ambitions to boost both of those sources to meet its local water supply goals, including recycling 100 percent of wastewater by 2035.

Under this new plan recycled water, which currently only amounts to 2 percent of the water supply, would make up a third of the city’s drinkable water supply in the future and some of that would be used to recharge groundwater. L.A. also plans to boost stormwater capture and is expanding the Tujunga Spreading Grounds, which infiltrates water back into the aquifer. This storage capability hinges on the construction of these new groundwater treatment facilities to ensure the water can be clean enough for drinking after being pumped back out.

Finding the Money

Local environmental groups have lent their backing to LADWP’s plan. Charming Evelyn, chair of the water committee for the Sierra Club’s Angeles Chapter, says the organization supports the groundwater cleanup effort and hopes more money can be found to complete the remediation, while local residents continue to work on conservation efforts, too.

LADWP’s groundwater remediation plans won’t come cheaply. If all four projects come to fruition, construction costs are estimated to be $573 million. However, says VanWagoner, the cost of building the new treatment facilities will be less expensive than continuing to rely on imported water from Metropolitan Water District. And the added resiliency it gives the water agency is a hidden value. “There’s a lot of really compelling reasons to do this.”

The agency has been working on different funding streams, but VanWagoner says all of these projects are in LADWP’s budget.

Evelyn isn’t concerned about the burden falling to ratepayers, though. “It’s the ratepayers that are going to benefit in the long run from it,” she says. “Having more local water will be cheaper than bringing in imported water.”

And she’s happy that it would boost local water supply without requiring L.A. to turn to ocean desalination plants, which have large greenhouse gas footprints and other environmental consequences, as other coastal areas of California have already done.

On top of that, she adds, residents are eager to see money spent on new water projects.

In 2014, while California was parched with drought, the state’s voters passed Proposition 1, a $7.5 billion water bond to help fund everything from new water storage projects to water pollution cleanup.

LADWP has tapped into that source. According to VanWagoner, the agency was trying to offset ratepayer fees with state and federal funding. After the first round of allocations from Proposition 1 were distributed, LADWP received $44.5 million to implement the North Hollywood West facility — half the money they needed for that project. Three of the agency’s other projects each received $2 million planning grants.

Meghan Tosney, an engineer in the financial assistance division of the State Water Resources Control Board, says the allocation for North Hollywood West is the board’s largest so far. “The project is definitely huge for them as far as water supply and it’s a contamination issue the region has been struggling with for a long time,” she says.

The well’s not dry there yet, either. The State Water Resources Control Board will make a decision this summer on the second round of funds allocated through Proposition 1 and a third round could take place in 2020, says Tosney. LADWP is vying for nearly $260 million to help build the Tujunga Central and North Hollywood Central treatment facilities.

The Responsible Parties?

The allocation process for bond money is a bit slow-going, but it’s not nearly as long a process as one of the other avenues LADWP has been following in tandem — using its legal team to chase down “potentially responsible parties” — the initial culprits of pollution.

LADWP’s legal team “has been pursuing potentially responsible parties with the hope that going to court or through legal settlements, we can offset some of the costs from those who were responsible for the contamination in the first place,” says VanWagoner.

The process for finding potentially responsible parties is both complex and frustrating, he says. There are thousands of potential polluters who operated during decades of lax environmental regulations. It can take years of research into historic records, including finding out who purchased and used different chemicals, to begin to identify those responsible.

“There are a few large parties still out there,” he says. “Unfortunately, there were many, many small businesses that have come and gone over the decades. A lot of these places no longer exist — there’s simply no one to go after anymore.”

The EPA has already been at it for decades.

The agency has investigated 4,000 different businesses that operated in the valley and may have been responsible for groundwater pollution — everything from large defense companies and auto mechanics to landfills and small dry cleaners. An initial settlement with 37 parties resulted in the first round of treatment plants through the Superfund program. Last year’s settlements with Lockheed Martin Corporation and Honeywell International, Inc., both also part of the earlier settlement, will fund $21 million to expand groundwater-treatment facilities and conduct additional studies in the parts of the North Hollywood Operable Unit.

A Regional Solution, a Federal Responsibility

The engineering and logistics of L.A.’s vast water system that serves 4 million people — the thousands of miles of aqueducts, canal and pipelines, the hundreds of groundwater wells, the treatment plants, reservoirs and spreading grounds — may not be common knowledge to most local residents, but water consciousness still permeates.

Recurring droughts and a modest 15 inches of rainfall a year help shape those attitudes.

The state’s last drought, from 2012 to 2016, spurred a 20 percent decrease in per capita water consumption in L.A. People care about having enough water, especially clean water, says TreePeople’s Montañez, who grew up in the San Fernando Valley and was the former mayor the city of San Fernando.

But when it comes to ensuring a long-term resilient and local supply, the region will need more than just the efforts of local residents — state and federal agencies have a role to play, too, she says.

“The valley contributed so much to the development of the country — the United States was so strong in defense, in agriculture and in other industries that came from here,” she says. “The pollution happened because environmental regulations weren’t that strong and people weren’t holding the polluters accountable. So, now we have a problem, but the technology exists to fix it.”

Cleaning up the groundwater should be one of the region’s biggest priorities, she adds. “Everyone should care about this — the groundwater basin in the valley is one of the most important aquifers in the West.”

This story was supported by a grant from the Society of Environmental Journalists’ Fund for Environmental Journalism.