Vanity Fair may not be the best source for reliable scientific information, but this cover is typical of an idea that’s becoming popular in the memesphere: that the Roman Empire fell because of climate change. Alas, this means stretching the data more than a bit and surprisingly, the opposite may be true: the climate changed because the Empire fell. Read on! (image source)

We have a problem with history: we often try to frame the past as if it were the same as the present. And that means projecting on the ancient our own troubles and fears. Add to this the difficulties we have in dealing with complex systems, the kind of systems that normally behave the way they damn please, and the results are often a complete mess.

The fall of the Roman Empire is a case in point. Maybe you know that in 1984 the German historian Demandt listed 210 (!!) causes proposed for the fall. It is fun to read how people just transferred to the Roman society whatever they were afraid of, from Communism to Culinary Excess.

In more recent times, we started being worried about things that weren’t well known in the 1980s. One is the decline of the energy return on energy invested (EROI), which is a true problem for our fossil-based society. It is much less obvious that it was a problem the ancient Romans and I wasn’t impressed by the attempts of Thomas Homer-Dixon to paint the Roman collapse as the result of an EROI decline. No data, no proof, just vague analogies.

Nowadays, our worries have shifted to Climate Change and, as you might have expected, the idea that Climate Change can destroy civilization has been projected to the fall of the Roman Empire. You can read a popularized version of the idea on “Vanity Fair” (see above), but also serious researchers seem to have bought into it. For instance, Kyle Harper, professor at the University of Oklahoma, titles his 2017 article “Climate Change Helped Destroy the Roman Empire.”

The kind of climate change that’s supposed to have destroyed the Roman Empire is different than the current version: we are affected by global warming, in ancient times the problem seems to have been global cooling. Lower temperatures negatively affected agriculture, that caused famines and pestilences, and that reduced the population. Then, bang! The Empire collapsed. The problem with this idea is that the dates, simply, don’t match.

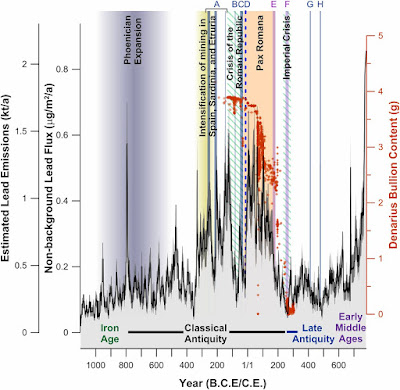

I already discussed this matter in a brief post in 2016, but let me go back to the story with more details. The Western Roman Empire officially disappeared during the 5th century, but the real collapse was much earlier. Here are data on lead and silver pollution in Roman times from a 2017 paper by McConnell et al. Likely, these data are a good proxy for the whole Roman economy.

You see how the decline of the Empire started around 100 CE and the collapse was complete around 250 CE, a true Seneca Collapse, faster than the growth that preceded it. That corresponds to what we know from the historians of the time.

Now, how about climate? Do we see something happening during the economic collapse? Here, the data are much less certain, but a “proxy” of temperature can be obtained from measurements on tree rings. Here is a data set published in 2011. More recent data substantially confirm these results.

First of all, note the uncertainty in the data: variations under ca. 0.5 °C are probably not significant. Also note how two different sets of data, marked with the black line and the red line, do not match exactly. But some “dips” seem to indicate significant temperature drops — here, too, we may have a kind of “Seneca Collapse” of the temperature. The most intense drop occurred in mid 6th century CE with, it seems, a full 2 °C temperature decline.

Now, compare with the data of the previous figure on the Roman economy. Clearly, there was no significant cooling during the economic crash of the 3rd century AD. Temperatures started falling, badly, after the crash. And when temperatures reached their minimum – around the year 600 CE, the Western Roman Empire was only a memory. Of course, if you want to say that “A” caused “B,” at least it should be that A precedes B!

Besides, you can see that other correlations just don’t work the way they should if you want to blame climate change for something bad that happened to the Roman Empire. Consider the decrease of temperature in mid 1st century BCE. It is marked in the figure as “Roman Conquest,” correctly so because Caesar’s military campaign in Gallia was in full swing at that time: the Roman Empire was probably at its peak power. If cold is supposed to be able to cause the fall of an empire, it surely didn’t do that at that time!

So, we can conclude that, no, the Roman Empire didn’t fall because of climate change. It is one more of those “explanations” that don’t explain anything and that will become part of Demandt’s list, together with “Tiredness of life” and “Escapism.”

But let’s consider the data a little more in depth. It looks like they are telling something to us. Could it be that the opposite conclusion holds? That is, it could it be that the climate changed because the Empire fell?

Let’s follow this line of thought. We know that the Roman collapse was accompanied by a considerable decline in population. It is extremely difficult to have reliable data on this point, but it may be that the maximum European population in Roman times was of some 35 million people at the peak, then it shrunk to only 18 million inhabitants in 650 CE.

Depopulation is both cause and effect of the decline of agriculture and, with less agricultural land, forests can regrow. And, of course, forests tend to absorb CO2 from the atmosphere, that affects climate by lowering temperatures. According to a hypothesis put forward by Victor Gorshkov and Anastassia Makarieva, the effects of forests on climate may be even larger because of the biotic pump mechanism. It is a complicated story: it mainly affects rainfall, but it also cools the land.

If we look at the figure above with forest extents in mind, we see that some things start clicking together. Consider the temperature drop when Caesar conquered Gallia. We have no data on how many people his troops killed, but you can read a chronicle of the war written by Caesar himself, the De Bello Gallico, and you can see that it was no gentleman’s war. Caesar’s troop not only devastated Gallia but surely also brought back to Rome large numbers of Gauls as slaves. A depopulated Gallia may well have seen its forests regrow. Something similar may have taken place earlier on, during the 3rd century BCE, when the Celts expanded all over Europe.

So, things seem to make sense: depopulation and reforestation may really cool the Earth. But, also, a lot of caution is necessary: the matter is complicated and the data are scant and uncertain. Things become even more complicated with the “Little Ice Age” which also appears in the graph above, starting approximately with the 15th century CE. In this case, in contrast with the previous cases, the cooling occurs in correspondence with strong growth of the European population, although punctuated by various disasters in the form of plagues and famines. Maybe it was the depopulation of the North American continent that caused extensive reforestation and hence cooling. But the data are uncertain at best, with some interpretations explicitly denying this effect and proposing that the cooling may have been related largely to volcanic activity.

As you see, this story both uncertain and fascinating. It will take a lot more work before we’ll be able to disentangle the various factors that affected climate in historical times. I don’t claim here to have said anything new on these matters, but I was impressed to find so much work pointing at the strong interaction between human beings and climate — even before fossil hydrocarbons started to be called “fuels”.

The Earth’s ecosystem is a typical complex system. It reacts to perturbations, even minor ones, sometimes very strongly. Don’t expect it to remain stable just because it has been stable up to a certain moment. Remember that a pebble can cause an avalanche and don’t forget the straw that broke the camel’s back. Then, think of how large is the forcing generated in our times by the combustion of fossil fuels, maybe orders of magnitude larger than anything our ancestors could do. We are moving toward interesting times (as in the ancient Chinese malediction).

(h/t Steve Kurtz, Franco Miglietta, Stefano Caserini, Paolo Gabrielli)