In 1979, celebrated author Joan Didion began her essay collection The White Album with the famously potent line: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.”

Forty years later, this elusive human truth might well be the most important sentence for ensuring the future of humanity in an every-warming world.

“All the world’s main scientists are lined up,” says climate psychologist George Marshall. “We have this amazing amount of material, we can see with our own eyes and experiences that something weird is happening out there. People accept the problem.

“And yet they don’t believe in it. It doesn’t seem to affect them in any way.”

The antidote, he wrote in his 2014 book Don’t Even Think About it: Why Our Brains are Wired to Ignore Climate Change, is not more research, facts and dire outlooks. Rather, what the world needs is narrative. Communication. Stories about the future that cast each listener as a protagonist, whose values and most cherished parts of life are put up to the ball of fire in the sky to be illuminated in full – and burn, if kept there unprotected.

The facts about climate change have never been bleaker. In the past year, hundreds of scientists worldwide have pooled their research to tell that 1 million species are at risk of extinction. If global warming isn’t limited to 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2040, then 99 percent of coral reefs could die, and 50 percent of people could be living under water stress. Globally, a Belgium-sized area of primary forest was lost in 2018, and carbon dioxide emissions rose by 3.4 percent in the U.S., the world’s second-highest emitter.

And yet, what widespread changes have occurred beyond trendy campaigns around Meatless Mondays and plastic straws? While climate strikes and Extinction Rebellion demonstrations cry out in streets, what masses are mobilizing in offices of power?

In London, young people take to the streets for climate strikes, March 2019. Roy, Flickr

Any action on climate change is better than none. But there remains a deep and terrifyingly dark chasm between the magnitude of effort to slow the changes we incur and the gravity of the destruction toward which we’re surely headed.

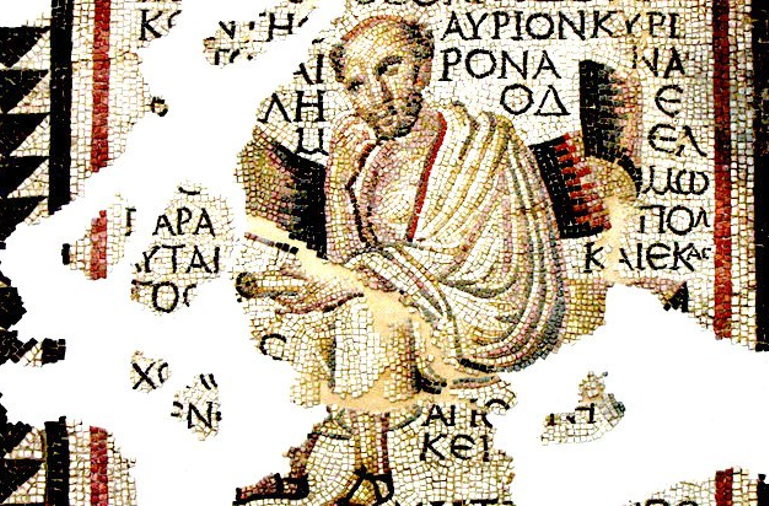

The power of narrative to affect human action has long been known. Gods are worshipped, wars are fought, leaders are elected and fortunes are spent because of what they represent. Socrates, in Plato’s The Republic, proclaimed stories as the most powerful way to educate. Aristotle penned an entire work, Poetics, on the power and components of a story. “The plot, then, is the first principle, and, as it were, the soul of a tragedy; Character holds the second place,” he wrote.

But if narratives around climate change are going to be effective, it is just as important that their creation be founded in fact as for the climate science they convey – which is to say, Aristotle got it wrong. Last September, researchers from McMaster University ran fMRI scans on the brains of subjects while feeding them short news headlines and asking the subjects to construct stories around the bytes. What they found was that the main network of the brain activated was the ‘theory-of-the-mind’ network, which focuses on characters. The plot came secondary – a result of the motivations, emotions and intentions of the people involved.

“Our brain results show that people approach narrative in a strongly character-centered and psychological manner, focused on the mental states of the protagonist of the story,” said Steven Brown, the study’s lead author.

A figure of brain scans of participants involved in the McMaster study on cognitive storytelling processes. Courtesy of McMaster University

Marshall has long claimed the same in regard to forming narratives around climate change.

“It’s a big mistake to think it’s about finding a killer message; it’s not. It’s about finding a process where people are participating in a storyline. It’s also how and where you’re hearing it, and who is doing the telling. But above all, they have to see themselves in it.”

“We are rational, but our drivers are many times emotional and social, and we have to know how to tap into that,” echoes Paula Caballero, a managing director at Rare, an organization that uses behavioral science to boost environmental conservation in communities around the world.

Biologically, what she’s saying is that a strong story must engage both hemispheres of the brain. The right, analytical side needs the literal input, the clear sequence of events and the facts for why they happened as such. The left, interpretive side of the brain will take this information and extrapolate meaning and feeling, contextualizing it within the listener’s life.

In branding speak, this translates into “logic” and “magic” – or, so have been the ingredients for the success of London-based global change agency Futerra, which works with brands and organizations to create narratives that will sell their “products,” whether that product be a Lancôme luxury perfume whose profits fund women’s literacy or boosting the Forest Stewardship Council’s logo to a requisite symbol consumers demand to see.

First, the logic: in order to successfully cause change, there must be a fact-based strategy, a step-by-step roadmap followed by rigorous accountability for those involved to make good on their commitments.

Then, the magic: a powerful, emotionally engaging story. “If you have really strong logic but no magic, that great sustainability plan is never going to see light of day,” says Hilary Tam, Futerra’s strategy director. “Because sustainability is so complex, abstract and far away, anything to make it less complicated or more relatable without being overly cliché will help. So we look at visuals and language to simplify it.”

A manifestation of the two put together is Futerra’s Good Life Goals (GLGs) – a set of 17 actions people can take to support the U.N.’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), each paired with a representative emoji. For example, GLG 3 is “stay well,” with five tasks such as exercising regularly and valuing mental health, depicted by a green emoji with a sweatband, to correspond with SDG 3, “good health and well-being.”

“I went to an MBA career day at Oxford University,” says Tam, “and all we had were the Good Life Goals emojis spread across our table. And you could see people gravitating toward us and the pretty colors not even knowing what we were there for.”

But while communication tools like emojis might cut across languages and cultures, Tam also hails technology for helping hyper-target narratives – think Netflix reformatting its options for each particular subscriber, or targeted ads on Instagram.

“We need to make a diverse audience tick, and technology enables us to be more diverse and inclusive without overwhelming or diluting the efforts,” she says. “If people don’t see themselves, nothing works.”

Sometimes, however, the obvious narrative for a particular audience isn’t the one that catches. Some 10 years ago, Rare launched a campaign to protect Siberian tigers in northern China and parts of the Mekong Delta. Now, the endangered species is multiplying with no help of conservation agencies on the ground, and only the work of local communities – yet the initial campaign hardly focused on tigers at all.

“Villagers were sick of hearing about tigers,” says Ann-Kathrin Neureuther, a senior manager at Rare, describing how an unthreatened deer was made the centerpiece of the campaign instead. Villagers were encouraged to reduce the use of the deer traps that the tigers would also walk into, and educated in the benefits that would come from conserving the ecosystem as a whole. “There’s a balance to strike between going big and making narratives small and contextual.”

But let’s return to the emojis – those round little faces that New York magazine described, around the time of their inception, as “a secret code language made up of symbols that everyone already intuitively understands” – love, giddiness, sadness, uncontrollable sadness, uncontrollable laughter, skepticism, a calm content.

One step back from this emotional DNA we all share will land you in the sphere of values. You might feel joyful after a wedding of a close friend. You might feel fear if that friend gets into a surf accident on the honeymoon. When our values, the parts of our lives that carry the most worth, are in play, the scorecard is marked with our emotions.

“I’ve argued for long time that climate change should not be thought of as environmental issue,” says Marshall. “The environment thing only works if it’s a sacred value, and for a lot of people, it’s not. But their identity, community, family or sense of country might be.”

The beautiful ring of “sacred value” comes in fact from the psycho-social academic lexicon, which has been defined by psychologists as a value that possesses “infinite or transcendental significance that precludes comparisons, trade-offs, or indeed any other mingling with bounded or secular values.” Would you accept USD 1 billion in exchange for one of your children? Marshall says he would not, because his children are beyond price.

“If climate change isn’t in this space of sacred values, then you get into financial conversations,” he says. “How do we show the things we have are threatened? This is the only way we have to break out of the cost-benefit cycle.”

In other words, making business cases for better behavior around climate change won’t evoke the amount of change needed; but engaging people’s sacred values first – and then showing that there might be resulting economic benefits – will. Making your home energy-efficient to save on bills might not resonate; investing in green living to have a safe, healthy, inviting space for your friends and family perhaps will. Plus, you’ll save some money.

Celebrity street artist Banksy comments on social and political issues through his public illustrations, such as this work in Los Angeles. Francisco Huguenin Uhlfelder, Flickr

Or, you won’t, and increasingly, that seems to be okay too. Tam says that consumers are waking up to the fact that their dollars are votes and choosing how to spend them more carefully, because their values are changing. Statistics are showing that millennials in particular are willing to pay a premium for brands that support social or environmental causes, she says.

“We always talk about this value-action gap. Once you ask someone to pay for it – buying organic – do they carry through? We’re actually seeing that gap close, and yes, they do.”

This is positive news for consumer markets, but it is still difficult to break out of funding-based conversations in the development world, says Caballero. Donor and electorate cycles allot certain amounts of money for certain periods of time, often demanding results be produced quickly rather than encouraging investment in long-term, more sustainable change.

Personalizing this in the context of her own country, Colombia, she says that if she were president, she would ban the use of the term baldío. Baldío is used to describe pristine reserves of the Amazon, palm-filled floodplains, “the most vibrant, biodiverse parts of the country,” she says. But baldío means “wasteland,” because these landscapes are not productive in the traditional, profit-driven societal sense.

From the standpoint of natural beauty and personal meaning, Colombians will also refer to these landscapes as the riches of the country, points of pride. But little is done to protect them, Caballero says, because of the prevailing narrative of their lack of productivity.

“Unless you’re able to change mindset of Colombians on what baldío means, you can’t shift the huge deforestation rates,” she says.

“We must work with essential critical mass that we have, which is the human mind.”