The UK is to raise its ambition on climate change by setting a legally binding target to cut its greenhouse gas emissions to “net-zero” by 2050, prime minister Theresa May has announced today.

The 2050 net-zero goal was recommended by the government’s official adviser, the Committee on Climate Change (CCC), last month. The CCC’s advice was requested following the 2015 Paris Agreement, which raised global ambition with a target to limit warming since the pre-industrial period to “well below” 2C and to make efforts to stay below 1.5C.

In a letter confirming the decision, May says: “Ending our contribution to global warming by 2050 can be the defining decision of this generation in fulfilling our responsibility to the next.” The UK would be the first member of the G7 group of major economies to legislate for net-zero. It joins others having set net-zero targets, including Sweden, New Zealand and Japan.

May’s announcement diverges from the CCC advice on some details, including the use of international “offsets”. It does not explicitly mention emissions from international aviation and shipping, but responding to questions from Carbon Brief the prime minister’s office says: “This is a whole economy target…and we intend for it to apply to international aviation and shipping.”

Draft legislation implementing the new goal must now be approved by both houses of parliament, in a process that could be finalised in a matter of days. The government says it will review the target within five years “to confirm that other countries are taking similarly ambitious action”.

- Why is the UK setting a net-zero target for 2050?

- How does the UK target compare internationally?

- What are the costs and benefits of going net-zero?

- Is the UK on track to reach net-zero emissions?

- Does the target include international aviation and shipping?

- What about emissions embedded in imports?

- What happens next?

Why is the UK setting a net-zero target for 2050?

The UK’s 2008 Climate Change Act includes a legally binding target to cut greenhouse gas emissions to 80% below 1990 levels by 2050. This was set in the context of international ambition to limit warming to no more than 2C above pre-industrial temperatures.

In 2015, the Paris Agreement changed the rules of the game by raising global ambition to “well below” 2C and adding an aspirational goal of limiting warming to 1.5C. The Paris deal also commits signatories to “balance” greenhouse gas emissions and sinks “in the second half of this century”.

This wording, widely taken to mean net-zero emissions, was reinforced by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in its special report on 1.5C published in October last year. This said global greenhouse gas emissions should reach net-zero by 2070 to limit warming to 1.5C, with CO2 at net-zero by 2050.

After the IPCC report, the government asked the CCC for advice on when the UK should reach net-zero emissions, in the new context of the Paris Agreement.

The CCC recommended net-zero greenhouse gas emissions be reached by 2050, excluding the use of international offsets and including the UK’s share of international aviation and shipping. It said the UK should reach net-zero faster than the global average because it is wealthy, has large historical emissions and has a “significant carbon footprint” in attached to imported products.

Animation: The countries with the largest cumulative CO2 emissions since 1750

Ranking as of the start of 2019:

1) US – 397GtCO2

2) CN – 214Gt

3) fmr USSR – 180

4) DE – 90

5) UK – 77

6) JP – 58

7) IN – 51

8) FR – 37

9) CA – 32

10) PL – 27 pic.twitter.com/cKRNKO4O0b— Carbon Brief (@CarbonBrief) April 23, 2019

Today’s announcement means the government has accepted the 2050 net-zero target recommended by the CCC. It has tabled legislation that will amend the Climate Change Act by replacing the “80%” headline goal for 2050 with “100%”. This means the UK target will officially be to cut emissions by “at least 100%” below 1990 levels by 2050.

The CCC also recommended separate targets of a 100% cut in emissions by 2045 for Scotland and a 95% cut by 2050 for Wales. The Welsh government wants to go further, targeting net-zero by 2050. Legislation for a net-zero by 2045 goal is moving through the Scottish parliament.

The CCC’s advice was criticised as too weak by some NGOs and academics, who called for the UK to reach net-zero well before 2050. The CCC said it had been deliberately conservative in its assessment of what was feasible and that net-zero by 2050 was “the earliest to be credibly deliverable alongside other government objectives”.

How does the UK target compare internationally?

Some smaller nations have already fixed net-zero goals in law or have signalled an intention to do so, including Norway (2030), Finland (2035), Sweden (2045), France (2050), Denmark (2050) and New Zealand (2050), while Japan has set a net-zero target for the second half of the century. A European Commission proposal for net-zero by 2050 has yet to be formally adopted.

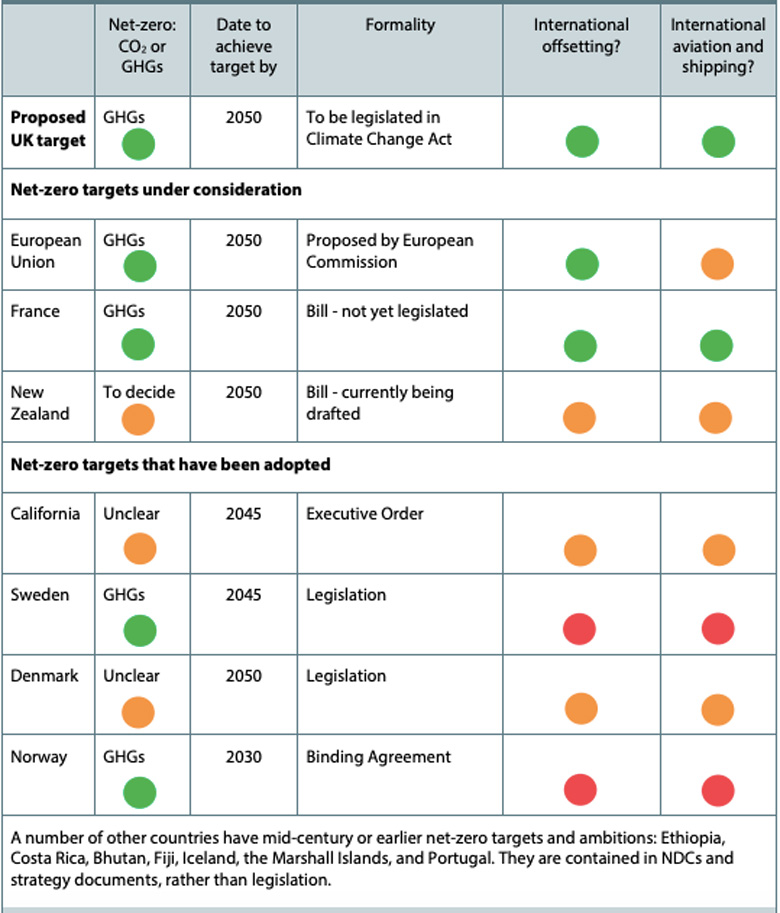

Emerging net-zero commitments in other countries. The columns show which greenhouse gases are covered, the net-zero year and the current status of the plan, as well as the approach to offsets and international aviation and shipping. Green indicates that all GHGs are covered, and marks an explicit aim to meet the target without using credits and to incorporate international aviation and shipping. Red indicates an explicit allowance for offsetting, or excluding aviation and shipping from the commitment. Amber indicates a lack of certainty. Source: graphic produced for the CCC’s May advice on net-zero.

The relative strength of these targets depends not only on the date and nature of the commitment – whether set in legislation or stated as government policy – but, crucially, also on the coverage of the goal. This makes international comparisons difficult.

In its advice, the CCC said the UK should include emissions from international aviation and shipping while excluding international emissions offsets. CCC chief executive Chris Stark said that this would put the UK “at the top of the pile” relative to other pledges.

The government has not explicitly agreed to the recommendation on aviation and shipping, while it has rejected the advice on offsets, as explained in more detail below.

What are the costs and benefits of going net-zero?

The costs and benefits of cutting emissions are a regular battleground for those that oppose – or support – action to tackle climate change. One common tactic is to highlight the costs without mentioning the benefits, or to add up cumulative costs over time to reach a larger number.

Ahead of today’s announcement, a letter from chancellor Philip Hammond was leaked to the Financial Times, which covered its contents under the headline: “UK net-zero emissions target will ‘cost more than £1tn’.” This figure is an estimate of the cumulative investment needed to 2050 and amounts to £50-70bn each year, the equivalent of 1-2% of UK GDP.

Hammond’s letter to May, page 1 pic.twitter.com/eQPVX4l6Gx

— Jim Pickard (@PickardJE) June 6, 2019

In its advice, the CCC points out that the estimated 1-2% of GDP that will need to be invested to reach the net-zero target is the same as was expected when parliament adopted the 80% by 2050 target. It also points to the “large benefits” – which it does not put a monetary value against – that will flow from reaching net-zero.

More importantly, the size of the UK economy could actually increase overall under a net-zero target, despite significant investments in meeting it. An independent expert committee for the CCC concluded: “[The] GDP costs of a net-zero target are likely to be small and could even be positive.”

Dimitri Zenghelis, who is a visiting research fellow at the LSE Grantham Institute, member of the CCC’s expert committee and a former head of economic forecasting at the Treasury, has written a blog arguing that the chancellor’s letter was “simply incorrect” to say net-zero would cost £1tn.

Zenghelis says that the costs of meeting the 80% goal were overestimated and that similar cost reductions would follow on the path to net-zero. He adds:

“Retraining and retooling programmes, energy efficiency measures and compensation schemes for low-income and otherwise vulnerable people will need to be implemented to help people and businesses adjust to the decline of some sectors as others are growing to take their place…[But] ambitious and early action, targeting net-zero emissions by mid-century, is the surest way to secure a thriving, productive and competitive UK economy in a low-carbon future.”

The government release announcing today’s news also stresses the benefits of going net-zero, which it says include “significant benefits to public health and savings to the NHS from better air quality and less noise pollution, as well as improved biodiversity”.

Writing in the Independent, climate minister Claire Perry says:

“No one says this will be easy and of course there will be costs. But what is the cost to our health and environment if we do not avert the breakdown of our climate, and with it the ecosystems that support the way of life of billions around the world?

“Climate experts estimate the benefits, including health and environmental, could almost fully offset the costs of moving to a net-zero emissions economy – and that doesn’t account for the huge economic opportunity of leading the global shift to greener, cleaner economy which is at the heart of the UK’s modern industrial strategy.”

However, the government is not publishing an “impact assessment” of the net-zero goal. Instead, it says departments will carry out their usual formal appraisals of the costs and benefits of each policy brought forward to meet the overall net-zero target.

In line with CCC advice, the Treasury is also set to carry out a review of the costs of reaching net-zero, including an assessment of the sectors and communities likely to be most affected.

Is the UK on track to reach net-zero emissions?

The ambition to cut the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions to net-zero by 2050 will need to be matched by policies commensurate with rising to the challenge. In his letter on the net-zero target, chancellor Philip Hammond makes this clear, writing:

“[W]e are currently off track to meet our existing carbon budgets…so the government would need to enact an ambitious policy response in this parliament for any new target to have credibility.”

In its advice, the CCC also emphasised the need for more ambitious policy to match the net-zero target, saying:

“Our advice is offered with the proviso that net-zero is only credible if policies are introduced to match…Current policy is insufficient for even the existing targets…A UK net-zero GHG target in 2050 is feasible, but will only be deliverable with a major strengthening and acceleration of policy effort.”

The CCC has previously highlighted the fact that almost all progress in cutting UK emissions has come from the power sector, whereas little headway has been made with heating and transport. This means the UK is set to miss its fourth and fifth carbon budgets for 2023-2032 by increasing margins, as shown in the chart, below. The scale of the challenge is magnified by today’s net-zero pledge.

Historical UK greenhouse gas emissions (dark blue line and shaded area, millions of tonnes of CO2 equivalent) and government projections to 2032 (light blue). These are set against the first five carbon budgets (red steps) and a net-zero target for 2050 (red line), as well as the current 80% by 2050 target (dashed yellow). Note that emissions since 2008 and the projections to 2032 show the UK’s “net carbon account”. The 80% by 2050 target shown here includes the CCC’s 40MtCO2 allowance for international aviation and shipping, which are not currently included in the carbon budgets. This effectively entails an 85% cut for the rest of the economy. Source: Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy emissions data and projections, plus Carbon Brief analysis. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

Under Section 17 of the Climate Change Act, the UK can use “flexibilities” to transfer under- or overachievement from one five-yearly carbon budget to another.

In February, the CCC gave “unequivocal advice” saying such flexibility should not be used in respect of “overachievement” during the second carbon budget period of 2013-2017. It said any surplus was due to external factors, including the recession, and not government policy. Using this surplus to help meet future budgets would “undermine” UK ambition, it warned.

Nevertheless, the government has confirmed in a statement to Carbon Brief that it will carry forward 88m tonnes of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e) from the second to the third carbon budget, effectively weakening that target, which the UK is already on track to beat.

Despite the decision to increase the third carbon budget by this amount, the government says it “has no intention of using this overperformance to meet Carbon Budget 3”. Instead, it hopes to “release” the 88MtCO2e at a later date.

The government is concerned that technical changes in the way the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions are counted – principally relating to peatland – might make it harder to meet legislated targets. It says it hopes to “release” the surplus after taking CCC on the impact of these changes.

However, there does not appear to be a legal mechanism for this “release” to take place.

The CCC is likely to consider this situation next year – as well as the implications of the new net-zero target – when it recommends the level of the sixth carbon budget for 2033-2027. It has also reserved the right to recommend tightening the goals for the fourth and fifth budgets.

Ultimately, the government says it will “retain the ability” to make up any shortfall against the UK’s legal targets by buying international offsets – in effect, paying for emissions reductions to take place overseas. This would be allowed under the Climate Change Act, but runs counter to the CCC’s advice, which says the UK should prioritise global action by excluding offsets.

The CCC does say that offsets “could provide contingency”, if policies to cut emissions at home end up falling short. It says it would give advice on the “acceptable level” of such offsets closer to the time they might be used and that this “should not be planned for”.

Does the target include international aviation and shipping?

The UK’s progress towards its legally binding climate goals is measured at the end of each five-year carbon budget on the basis of the UK’s “net carbon account”. This does not include emissions from the UK’s share of international aviation and shipping.

A decision by the end of 2012 on whether to formally change this position was built into Section 30 of the Climate Change Act. Despite CCC advice that these sectors should be included, the government of the day decided not to do so.

Nevertheless, the CCC has recommended each carbon budget on the basis that international aviation and shipping should be taken into account. It has done this by setting aside “headroom” for aviation and shipping, which effectively reduces the carbon budget for the rest of the economy so as to leave space for these sectors within the UK’s overall emissions pathway.

The CCC’s latest progress report explains the situation as follows:

“Emissions from international aviation and shipping (IAS) are, at present, formally excluded from carbon budgets but taken into account when budgets are set (i.e. the budgets are set to be on track to a 2050 target which includes IAS emissions.)”

The government has so far accepted this compromise arrangement. But the relative scale – and prominence – of the issue is set to rapidly increase, as aviation and shipping emissions continue to attract public scrutiny and as emissions from the rest of the economy decline.

Whereas aviation and shipping currently account for a relatively small share of UK emissions, air travel would be by far the largest remaining sector under the CCC’s proposed pathway to net-zero by 2050. Its residual emissions would have to be offset by removals – for example, through afforestation or bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS).

In a draft “explanatory memorandum” alongside the net-zero legislation, the government says:

“The government recognises that international aviation and shipping have a crucial role to play in reaching net-zero emissions globally. However, there is a need for further analysis and international engagement through the appropriate frameworks.

For now, therefore, we will continue to leave headroom for emissions from international aviation and shipping in carbon budgets to ensure that emissions reduction strategies for international aviation and shipping can be developed within International Maritime Organisation and International Civil Aviation Organisation frameworks at the appropriate pace, and so that the UK can remain on the right trajectory for net-zero greenhouse gas emissions across the whole economy.”

This suggests it would like the current compromise to continue for now. In a statement to Carbon Brief, however, the prime minister’s office implies this might eventually change, saying:

“This is a whole economy target…and we intend for it to apply to international aviation and shipping.”

The CCC is due to publish separate advice on aviation emissions in the coming weeks. It has already said that international aviation and shipping should be formally included within UK targets, starting with the sixth carbon budget for 2033-2037.

Carbon Brief understands that such a move might require primary legislation, whereas the net-zero target is being implemented via secondary legislation, which can be passed more quickly.

If international aviation and shipping are to remain outside the UK’s legal goals, then the CCC could recommend budgets for the rest of the economy that go below zero, so that the UK would still reach net-zero on balance.

The 2050 target is phrased as a cut of “at least” 100% below 1990 levels, effectively allowing for such a move, as Mike Thompson, the CCC’s head of carbon budgets, explains in the tweet below:

The “at least” was originally there to cover for possible exclusion of aviation (as rest of economy would need to do more). Same applies for #netzero: if ✈ outside then rest may need to be net negative

— Mike Thompson (@Mike_Thommo) June 12, 2019

What about emissions embedded in imports?

The UK’s carbon targets do not cover the significant carbon footprint associated with the goods and services it consumes that are produced overseas and imported into the country.

The level of these emissions embedded in imports increased steadily through the 1990s and early 2000s, but has stalled since the global financial crisis in 2008. In 2016, imports accounted for around 20% of the UK’s overall CO2 output, including embedded emissions.

The total amount of imported CO2 has barely changed in recent years, recent analysis for Carbon Brief shows. Measured on a consumption basis including imports, the UK’s carbon footprint has been falling in recent years and is at its lowest level in two decades.

The CCC rejects the idea that UK targets should be amended to include imports, arguing that the country does not control emissions in other countries and that these emissions will fall if global efforts to cut carbon are successful. However, its net-zero advice says:

“In pursuing a net-zero emissions target, it is important that the actions to reduce UK territorial emissions do not simply offshore these emissions to other parts of the world. Furthermore, actions that the UK can take to reduce its consumption emissions could be as effective in tackling climate change as actions to reduce territorial emissions…Overall, it is likely that the reduction in UK territorial emissions in our scenarios would result in a larger reduction in global emissions, particularly if policy is developed with lifecycle emissions in mind.”

It recommends policies including resource efficiency and waste reduction as being effective in cutting UK emissions at home and abroad.

What happens next?

The draft legislation on a net-zero target for the UK must be approved by both houses of parliament. The prime minister’s office tells Carbon Brief:

“The [draft legislation] will need to be debated and approved in both houses of parliament. They can choose to divide on it [hold a vote], or approve without a division if they all agree.”

Carbon Brief understands that this process could be completed within a matter of days, should the government wish to do so.

A “youth steering group” will be convened by government and the British Youth Council, with the aim of “advis[ing] government on priorities for environmental action”.

The government has also said it will “carry out an assessment” of the target within five years, to check that the UK is not acting alone and that companies are not facing “unfair competition”. The draft legislation does not contain any legal trigger that would automatically require a formal review of the net-zero goal in future.

Section 2 of the Climate Change Act already contains provisions allowing for the 2050 target to be amended in light of “significant developments in scientific knowledge about climate change, or European or international law or policy”. This provision is the basis for today’s net-zero legislation.