Almost precisely 10 years ago I wrote about the likelihood of a shortage of helium in the not-to-distant future in a piece entitled “Let’s party ’til the helium’s gone.” Last week worries about a helium shortage appeared in my news feed. It seems that we are indeed going to party ’til the helium’s gone as no steps that I know of have been taken to avert the inevitable shortage.

That the shortage comes as a surprise results from a certain scientific illiteracy about the makeup of the universe and the geology of the planet. More on that later.

It also results from a peculiar type of economic thinking that is pervasive today that states that when shortages occur of any commodity, prices will rise to incentivize exploitation of previously uneconomical resources and automatically solve the problem. This intellectually lazy pronouncement does not consider whether the new supplies will be affordable. (As I pointed out in another piece about helium in 2013, “Things do not have to run out to become unavailable.”)

The same lazy, unreflective line of thought cited above also asserts that if we “run out” of a particular commodity (or it becomes unaffordable which is the same thing and more likely), we will always find substitutes precisely when we need them in quantities we require at prices we can afford.

As I pointed out in my piece 10 years ago, there are likely to be no comparable substitutes for helium because liquid helium allows for maintaining temperatures near absolute zero (−459.67 degree F). These temperatures are essential for certain industrial, medical and research processes.

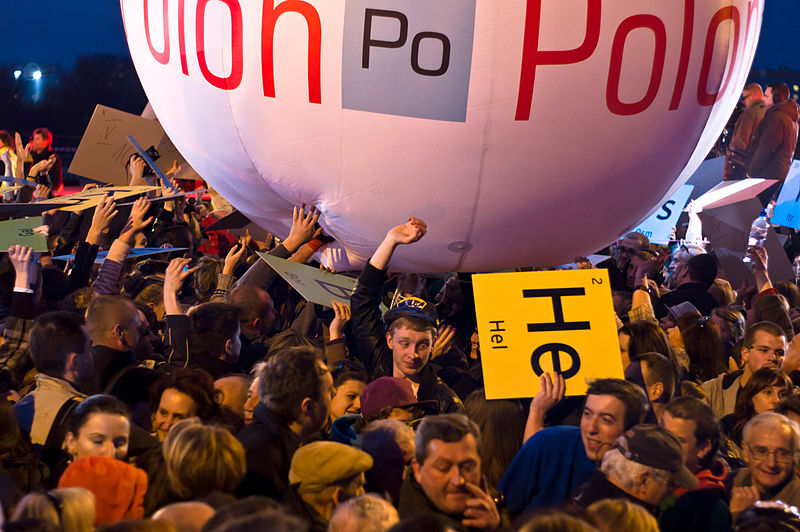

Magnetic resonance imaging used in medical diagnosis depends on helium. Helium is especially useful for superconductivity applications and research. Superconductivity is the ability of a substance to carry far more electric current at very cold temperatures. Helium is also critical in the manufacture of silicon wafers which are central to modern electronics including computers and cellphones. Given these and other critical uses, one would think that governments would step in to restrict the use of helium for nonessential uses such as party balloons. But that would require a repudiation of the flawed thinking guiding most of our economic policy.

Returning now to the uncompromising universe and planet we inhabit, let’s review why the economic thinking cited above will not help us much with helium. First, helium is an element not a compound. It cannot be synthesized from other more abundant substances. Second, even though helium is the second most abundant element in the universe—hydrogen is the first—helium is exceedingly rare on Earth.

Helium is formed by the decay of radioactive elements in the Earth’s crust. The helium then begins an upward journey that most often ends as it leaves the Earth’s atmosphere and escapes into outer space. A small amount is trapped in natural gas reservoirs. Helium is separated from natural gas in a processing plant. But few natural gas reservoirs contain concentrations of helium high enough to make them economical to separate.

So, here is something that almost no one is discussing about helium supplies: Helium extraction will almost certainly peak when production from the natural gas reservoirs containing economical amounts of helium peaks. Most of the world’s helium currently comes from long-ago discovered natural gas fields in the United States which are nearer to the end of their production life than the beginning. Some comes from Qatar and Algeria, both large natural gas producers.

Unless new natural gas fields containing economical amounts of helium are found soon—or one company prospecting for economical deposits of helium mixed with non-hydrocarbon gases succeeds in a big way—helium supplies are likely to begin a long, irreversible decline. Keep in mind that no one prospects for natural gas in order to extract the helium from it. Thus natural gas production largely dictates what helium gets produced. I am therefore skeptical that either new source mentioned above will prove decisive in averting such a decline.

There are many other rare elements—such as indium, gallium and tantalum used in cellphones and other electronics—upon which our modern infrastructure depends. The emerging story of helium suggests that we will NOT always find substitutes precisely when we need them in quantities we require at prices we can afford for such critical and rare materials. And, we as a society have not figured out what it will mean when we don’t.

Photo: “Laying the Mendeleev Table: Bielany versus Białołęka. Opening of the Maria Skłodowska-Curie Bridge in Warsaw” by Adam Kliczek (2012). Via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Warszawa,_otwarcie_Mostu_Marii_Sk%C5%82odowskiej-Curie_13.jpg