The word sustainability, were it up to me, would be extinct, wiped out, kaput.

Economists promise “sustainable economies” while business types explore “sustainability accounting.”

Greens promise a “sustainable future,” and even greener pundits swear that technology will deliver “global sustainability.”

The United Nations champions “sustainable development goals” as though SDGs were a delightful venereal disease.

But apparently every nation must set some SDGs, and go for it.

Why, there are even research chairs in sustainable development at universities. And I suppose, somewhere, there are people proposing to be sustainable journalists.

We have forgotten the original meaning of sustain, which stems from the Old French sostenir, meaning “hold up bear; suffer, endure.” In the 14th century — a period of pestilence and famine, it meant “endure without failing or yielding.”

As civilization collapses we are going to need that old word again.

But well-intentioned greens took a word with historic meaning and turned it into plastic soup with the Brundtland report published by the United Nations in 1987.

That document let the word loose on the world like feral cats in Australia’s outback by defining “sustainable development” as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

What sustainable meant in 1987 and means now is unlimited industrial and technological growth, or more of the same old bullshit because “the economy and the environment must go hand in hand, sustainably.”

To this day the great Canadian water ecologist David Schindler considers the word “sustainable” one of his pet peeves.

“It has been commandeered by industry, and they simply add it as an adjective to any new project in order to greenwash the public.”

He used to have a joke on his office door, tracking the frequency of use of sustainable over time. Given its exponential adoption, the joke estimated that sustainable would take the place of every second word by 2050.

Daniel Pauly, one of the world’s foremost marine biologists, also doesn’t care much for the plastic word. He argues that concrete plans for restoring damaged ecosystems should be our goal for fisheries instead of sustainability.

“Sustainability,” writes the University of British Columbia professor, “is a deceptive goal because human harvesting of fish leads to a progressive simplification of ecosystems in favour of smaller, high-turnover, lower-trophic-level fish species that are adapted to withstand disturbance and habitat degradation.”

Paul Kingsnorth, a recovering British environmentalist, argues that we are destroying the world in the name of sustainability, and he’s right about that.

He calls it “a curious, plastic word” that means “sustaining human civilization at the comfort level that the world’s rich people — us — feel is their right, without destroying the ‘natural capital’ or the ‘resource base’ that is needed to do so.”

That means taking what’s left of a battered paradise and paving it with more technical solutions including wind farms, solar arrays and undersea turbines.

As such Kingsnorth rejects the unsustainable worldview conveyed by plastic words. It “holds that the converging crises of our times can be reduced to a set of ‘problems’ in need of technological or political ‘solutions.’”

The conservationist Wendell Berry, always a straight shooter, has trouble with the meaningless word too. Whenever the poet farmer reflects on how the industrial revolution transformed his native Kentucky since 1775, he has to admit it hasn’t been sustainable.

“In fact, it has been the opposite. There’s less now of everything in the way of natural gifts, less of everything than what was there when we came. Sometimes we have radically reduced the original gift. And so for Americans to talk about sustainability is a bit of a joke, because we haven’t sustained anything very long — and a lot of things we haven’t sustained at all.”

Vaclav Smil, the energy scientist and European pessimist, hates the word sustainability too. He says it can’t even be defined.

“Sustainable for what? Over next year? Over 10 years? Over a millennium? On a local basis, on a planetary basis? I mean, there are so many time and space dimensions to it you cannot define what is sustainable. If somebody is boasting that what they are doing is sustainable, it’s a total laugh.”

How can a culture call itself sustainable, asks Smil, when it thinks it needs a two-ton pickup truck to carry a 200-pound person to a grocery store filled with food produced, packaged, shipped and displayed in ways requiring the most energy-intensive methods ever devised? “There is nothing sustainable. And it will not be for a long time to come.”

So let’s end this meaningless charade, and stop using the word sustainable to defend, as George Orwell would put it, the indefensible.

By any measure sustainability has become another foot soldier in the army of plastic words that have polluted our lives and politics.

These poisonous words have one goal: obliterate independent thought, the root of freedom.

Orwell, of course, identified the proliferation of these corrosive words in 1946 in his famous essay “Politics and the English Language.” It is a rare piece of writing that deserves rereading every year.

At the time Orwell argued that political writers were becoming very astute at gumming together long strings of meaningless words (class, progressive, values) as well as scientific technical jargon to obscure facts and kill clarity.

What are ‘plastic words’ and why do they pollute our language? Here’s a definition.

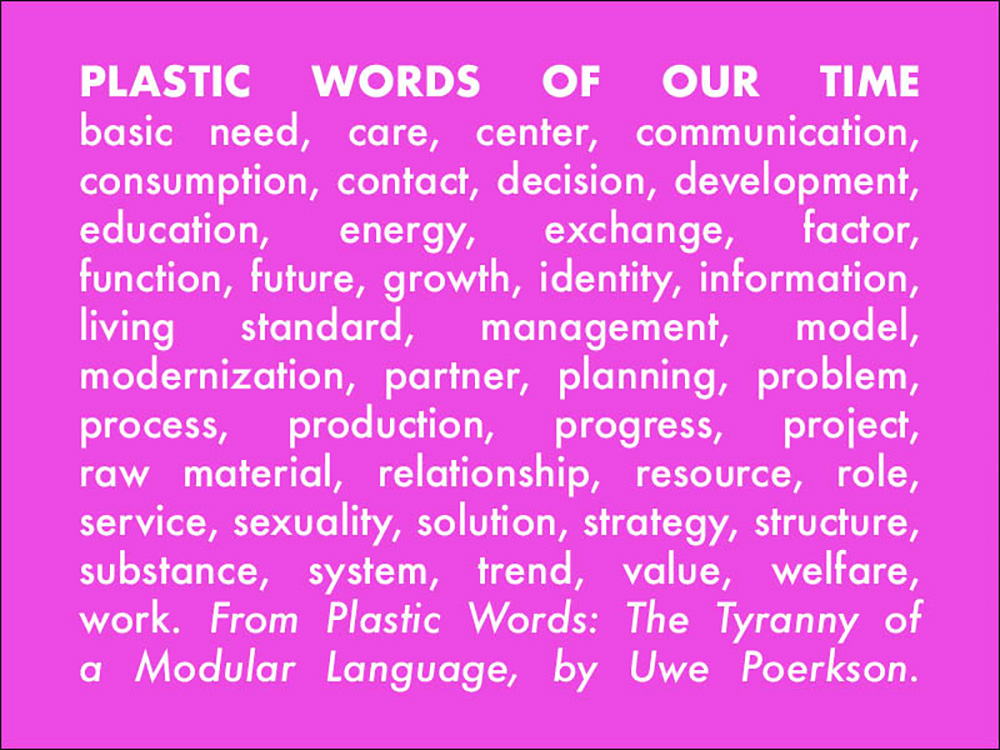

Nearly two decades ago the German linguist Uwe Poerksen provided a thoughtful update on the relentless pace of language degradation.

He called the world’s new global vocabulary plastic words, and warned that they were undermining real language as fast as plastic was filling the ocean. (If you can imagine the impact that five trillion pieces of floating plastic on the seas has on birds and fish, you will have a small inkling of what plastic words have done to our ability to act, talk and think.)

Much like Orwell, Poerksen compiled a list of plastic words and many, such as progress, are the same. But the machine world has thrown up new ones and Poerksen included on his list words like model, identity, growth, relationship, value, living standard, energy, production, care, centre, strategy, resource, system, information and process.

We could add a whole list of digital ones too.

The amazing Lego-like quality of these words allows their proud users to reassemble them into trains of nonsense such as “progressive resource systems” or “information values” or “sustainable production centres.”

Poerksen explained that plastic words largely came from the world of science and technology where they once had some precision. Removed from their original disciplines, they have little or no meaning but lots of authority.

The linguist feared that their hollowness invited empty thinking and promoted plastic living.

Poerksen also noted that modular words share a long list of modern characteristics that support technological living.

For starters they lack definition and possess no sense of place or history. They frequently replace precise words such as hydroelectric dams with meaningless phrases such as “clean energy.”

They evoke no images and brim with technical positivity. They reduce a complex field to a single denominator.

Why bother with the difficulties of processing bitumen or the hazards of hydroelectric power when a politician can evade consequences by simply championing energy systems?

(The Scottish writer Robert Macfarlane has cogently argued that the more we employ plastic words like the environment or techno jargon, the more we cull real words from our dictionaries like acorn, ash, bluebell and buttercup.)

In the end, plastic words supplant the natural and the precise in our language with the artificial and meaningless.

It is notable that Poerksen didn’t include sustainable or environment in his original 1995 list, but they are plastic building blocks nonetheless.

By putting these two modular words together, any politician can justify the flooding of farmland or the fouling of coastal waters by saying he’s just building a “sustainable environment.”

Poerksen, like Orwell, had no doubt about the goal of plastic words: he considered them a necessary language for “an international dictatorship.”

“In their usage the function of the discourse dominates, not its content,” wrote Poerksen. “These words are more like an instrument of subjugation than like a tool of freedom.”

Corporate sharks and public relations people embrace these plastic words like children because they can be used, like a Lego block, to fit every situation.

Who, after all, can reject the pleasantly sounding nonsense of “sustainable resource development.”

The media repeats this easy expression every day because it hides the totally fucked truth: degraded fisheries, diminished forests and eroded farmlands.

Justin Trudeau, a plastic politician, employs a full Lego vocabulary.

He even promised Canadians a plastic future by giving us a “a country even more beautiful, sustainable and prosperous than the one we have now.” How marvellous!

So far he has delivered a garbage heap of broken promises on electoral reform, climate change, transparency and government integrity. But the globe’s new Lego language makes it all sustainable.

Given what’s happening to the language, it is easy to understand why plastics will outnumber the world’s fish in the ocean by 2050.

So try something new and get uncivilized. Banish plastic words from your vocabulary, just as you might eliminate plastic from your household.

And whenever you hear the word, “sustainable,” just laugh long and hard.

Or shout “bullshit.” ![]()

Teaser photo credit: Marine biologist Daniel Pauly of UBC Common Sense Canadian video interview.