Failing to learn from past mistakes is the only truly unforgivable mistake in science. And on climate change, the scientific community (by and large) has been criminally negligent when it comes to observing — and especially learning from — its own track record. This blog post is a postmortem in 4 acts: an anatomy of failure, so that we can hopefully learn, act and change. Fast.

Act 1: Science as success

Let’s get one thing out of the way, shall we? The physical science of climate change has been a resounding, phenomenal, triumphant success. As a colleague from the University of Leeds recently put it, “We’ve been right for decades.” This makes the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change first Working Group (on the physical science) assessment reports an absolute dawdle to write up: “Still right!” [That’s a joke, by the way. There are always absolute stacks of new science to report on: just the large lines of it have not budged at all.] So there is not much to learn from there in terms of failure. Well done, physical scientists, you’ve observed & modeled external reality. You aced the case.

Act 2: Failing upwards

Let’s get a second thing out of the way. Science, as a whole body of institutions, people and knowledge, has failed on climate change. It’s not been alone in failing (governments and industry probably did most of the work, to be honest), but it did. “How dare you say we failed?”, I hear you howl, “We published papers! We advised governments! We wrote long, exhaustive, definitive reports! We were even awarded a Nobel Prize in long, exhaustive report-writing!” That’s all true and very nice, certainly, and reflects herculean efforts. But the proof of failure is not in the pages of reports or the records of advice to governments: it’s written large in the sky, in the upwards trend of emissions year-on-year. Being right on the physical science, it turns out, is not enough — not by far.

In Alcoholics Anonymous, the first step is admitting that one has a problem, and that this problem is beyond our current means to solve. I’d like to propose to the scientific community that we have a huge problem, one that that our current approaches are not solving. The first step to future success is surely acceptance of present and past failure: and we have spectacularly failed to curb or even slow down increases in greenhouse gas emissions. Despite decades of being right on the science of the immense threat these emissions pose, our science has not been sufficient to address and halt this threat. It’s time to sober up, accept we have a problem, and fundamentally rethink our roles and strategies.

Act 3: Ingredients for a perfect failure

Fine, we failed. It’s really, really bad. So how and why did we fail? And what can we learn from our investigation to stop failing, and start succeeding, in the present and future? After reading a bunch (including by the excellent Naomi Klein, Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway), I’ve come up with the following ingredient list for a perfect failure.

1. Trying to exist outside history

The scientific endeavor, since at least Enlightenment & Newton, tries to see its contributions as existing outside history and culture. If something is scientifically true, it should be true before it was “discovered” and for all eternity after. This is a lovely idea in theory, but with devastating consequences. Because no matter the eternal truth of a scientific finding: its interpretation and translation into understanding and action relies upon the cultural and historical context surrounding its discovery. So scientists disregarded history at great peril to the uptake of their findings. And the historical context of the late 20th century should have been taken much, much, much more seriously by scientific institutions and communities, because it included an ominous domination of neoclassical economic thinking in politics and culture, and a circumscribed, idealized role for scientists in public pronouncements and public life. Both of these will have to be challenged full-frontally before progress can be achieved.

2. Technocratic and apolitical aspirations

Partly as a result of descending from the Enlightenment, partly as a result of the structure of scientific institutions (universities, academies, national research centers), partly because this model worked relatively well for a long time without needing to be challenged, many scientific disciplines took on the idealized position of remote, neutral observers, staying well apart from the object of observation, emerging from their ivory towers to bestow impartial pronouncements on the busy world around. Of course, this vision often had nothing whatsoever to do with reality, where scientists participated avidly in some of the best and worst actions of their societies (wars, colonial conquest & genocide, but also medical, public health & education advances, combating inequality, trying to improve urban planning, etc). However, this vision has led to the ossification of what is considered to be an ideal scientist, and how many scientists would like to see themselves: as purely impartial, technocratic advisers to the world, without any political bias or perspective.

This perspective has led, among other things, to a dominance of economics in the way physical impacts and technological transitions required by climate change are considered, because economics is viewed as the apolitical social science (spoiler alert: it’s not. Much more on that in the section below). But even further, this has led to a fatal lack of consideration and engagement with broader social reality, including consideration and analysis of social systems. Climate impacts will tear through social systems and disrupt them. Technological transitions will either happen (or not) depending on experimentation and adoption within social systems. An insistence on science as purely apolitical and technocratic thus leaves a blind spot the size of humanity in how climate impacts will affect us, and how we might respond and act proactively.

Our aspirations to being apolitical have led us to not study the political system itself, its power structures, relations to fossil fueled industries, and so on. That’s a pretty large weakness, in hindsight, and one that left the scientific community extremely vulnerable to attacks by the fossil fuel lobby (see “Merchants of Doubt” by Oreskes & Conway). Our insistence on being apolitical made us sitting ducks for very politically-motivated attacks, which are still ongoing.

A final problem with the aspirations to being purely technocratic and apolitical advisors to power is that we have been generally averse to take our scientific findings directly to the people, through general public level communication (including through talks & other media) and pre-university education. We have been satisfied with sitting back and putting out long and fairly technical language reports, leaving the work of translation and mass communication to others, as sort of a trickle down mechanism, that was supposed to happen automatically. Unfortunately, again, this didn’t happen as we thought it should. Sure, David Attenborough finally made a documentary about climate change. But this is very late in coming. We should have been getting into school curricula, giving public talks, engaging with television and documentary-makers much, much, more than we have. Sadly, an insistence on keeping to our pristine science has led to woeful levels of public lack of information or downright misinformation. It didn’t have to be this way.

3. Dominance of neoclassical economics

The dominance of neoclassical economics, and its focus on market equilibrium (“market fundamentalism” according to Oreskes & Conway), looms large in the story of the failure to act on climate change. From the perspective of scientific effectiveness, it acted in several specific and pernicious ways, including shielding the spider at the center of the web: fossil fuel industries.

- Because of disciplinary divisions, and a failure to learn critically across disciplines, neoclassical economics is seen, from the perspective of physical scientists, as just plain economics: the full, established, “true” science of how we understand, measure and model economies. Physical scientists thus don’t know that pretty much all axioms underpinning neoclassical economics have been disproven or never occur in reality (perfect markets, rational actors, etc etc), or indeed that its most ardent champion, Milton Friedman, positioned neoclassical economics as a reality-free zone, where models based on complete fictions would be acceptable, and used his scientific “understanding” to advance extreme right-wing policies under the pretense of free markets. Neoclassical economics is the furthest thing from apolitical, but it has been very successful at presenting itself as such. To paraphrase the Usual Suspects “The greatest trick economics ever pulled was convincing the world it was a neutral science.”

- Again due to disciplinary divisions, economics was not understood as one large and diverse aspect of social sciences writ large, it was seen as the gateway science: an exact, mathematical, predictive body of tools through which physical scientists could translate their findings, and grasp and change unwieldy political and social systems. Other social sciences (psychology, sociology, political science a distant third) were seen as subservient to economics, or tractable through economics. Hence economics dominated the models and understanding of how climate impacts would affect societies, and how they would prevent or respond to them: through a simple equilibrium cost-benefit calculus, reality be damned.

- Neoclassical economics was also understood as the gateway to policy and real-world “very serious person” relevance. Both scientists and politicians took for immutable the dominance of market-based thinking in decision making, and thus insisted, to an extent completely out of sync with the gravity and urgency of the situation, on identifying “cost-optimal” pathways for policies. The misguided hope was that these pathways would then be followed, despite year after year of delay. Fool me once, shame on you, but what justifies a continued hope in identifying these pathways and presenting them as possible after decades of failure to adopt them?

- An emphasis on market-based thinking also warped the understanding of how large social, economic and political change happens out here in reality. Climate scientists believed the neoclassical hype that decisions & change happen through shifting cost-benefit equilibrium in markets, when nothing could be further from the truth. Out here in reality, markets are changed by large and powerful players (governments & industries, sometimes social classes) to serve their purpose. The decisions play out in market terms, but are made far upstream through subsidies, protections, investment & tax instruments, etc. Trying to change an economy by shifting the balance of the market is like the tail wagging the dog: a false understanding of causal reality. Focusing on market-based change was a devastating decision, as was the almost total ignoring of social and political change (despite these being the real movers underpinning any market change).

- The dominance of neoclassical economics comes at the expense of other, potentially far, far more effective, avenues of social change, including activism, social movements, electoral politics, deliberate divestment, legal challenges too fossil fuels, and so on. These have been cruelly neglected in comparison with economic-focused aspects.

- A neoclassical lens comes at the expense of a systemic understanding of the real causal drivers of the economy. I believe these have to do with capitalism as the structural foundation of our economy. I’ve written about this here and here. One can agree or disagree, but the shocking aspect is how little discussion there has been of systemic economic structures, including the power held by some of the largest and most powerful industries ever to exist, and which have been the main drivers of climate change.

4. Scientific positivism & insistence on exact models

Again back to Oreskes & Conway and their excellent “Collapse of Western Civilization: a View from the Future”, where they ascribe one of the reasons for our failure on “scientific positivism”: an insistence on overwhelming statistical proof. As they write, “These practices led scientists to demand an excessively stringent standard for accepting claims of any kind, even those involving imminent threats.” David Spratt & Ian Dunlop added to this understanding by explaining how the IPCC reports have emphasized middle ground findings (averages) rather than the full scope, resulting in downplaying “fat-tail risks”, which are sadly plentiful in climate science. Moreover, according to Spratt & Dunlop, a positivist preference for theoretically perfect (“fully-coupled” rather than heuristic) models has also resulted in systematically understating the risks of climate impacts: at the scale & complexity of earth systems, theoretical perfection in understanding feedback loops is understandably too high a bar. Yet at the same time, we’ve been under-reporting the results of heuristic models based on robust past observations and trends.

These various factors of over-caution in scientific all point the same way: to under-informing public and politicians of the true scope of climate risks.In the latest IPCC Special Report on 1.5 degrees, where the impacts were divided according to future temperature rise above pre-industrial levels, some of this fog was lifted, and large difference of impacts at 1.5 versus 2 degrees Celsius of warming was shown clearly (WRI has a good summary). Of course, the national commitments to the Paris agreement put us on a trajectory above 3 degrees, and since these are non-binding, and many countries are not on track to achieve even these too modest changes, we may still be on track for 4 or more degrees, a temperature where the term “cataclysmic” is no longer hyperbole. One of the reasons that the Special Report was able to paint this clear picture is because we are already at roughly 1 degree of warming above the pre-industrial era, and have left the agriculture-sheltering geological era of the Holocene behind.

Climate impacts are no longer just in remote models, they can be observed all around: in incidence and severity of droughts and severe weather events, in arctic ice drops, in glaciers melting away, in sea level rise, in ecosystem breakdown & mass species die-offs. And pretty much regardless of impact type, the severity of the observed response is on the far bad side of the modeled one (note that the heuristic models tend to fare better)— because of these various types of scientific over-caution. We have been under-warned about what is coming down the line.

There is another aspect of the scientific issues with understanding and reporting the evidence: because of the positivist insistence on exact models and high-level statistical proof, the systemic aspects of interconnected earth systems, often known under the term “tipping points” (see section 3.5.5 of chapter 3 of the SR1.5), has been under-explored in models. Part of this is understandable: if your model is based on continuous and rather smooth changes, and how they respond to each other, modelling a cliff-edge event is obviously outside the range of the model’s capacity. However, that doesn’t mean this modelling or understanding shouldn’t be attempted somehow, and the fact remains that we have some of our biggest blind spots in understanding some of the most catastrophic and entirely plausible, but non-gradual, impacts of climate change.

Act 4: Moving forward

If we can agree we’ve failed, this is already a step forward. I’d like to open up debate rather than shut it down: the reasons I listed above are my personal interpretation, based on sparse reading. These are not my areas of specialism. I do believe we need to have this discussion, though, and fast, because we have to move forward very differently than we have moved in the past, in order to avoid more lost decades of disregarded science. Below are my conclusions, others may have different ones.

1. Take social science & social systems seriously

Learn history, learn about larger economic theory (Heilbroner here is a wonderful start), learn about social change beyond narrow “policy window of opportunity” frames. Read about past social movements and how they achieved change: I wrote something about non-white struggles here, for instance. Try to take a systemic perspective, and understand how technology, politics and economics are intertwined throughout history.

2. Get out there. Communicate. Advocate.

I firmly believe that Exxon-Mobil and associated fossil-fuel industries, through their denial machines, highly funded disinformation and lobbying, killed the Honest Broker as a viable model of scientific communication. We have to invent new ones. I believe the best antidote to these massive machines of disinformation, which are still at work and will continue to wreak havoc all around us, is to get out there and be personal, passionate, insistent voices for change. We can have integrity and activism at the same time: indeed, how can we be true to the implications of our scientific findings if we do not? I am proud and humble to follow in the footsteps of scientists with the immense integrity of James Hansen, but this needs to be come the norm, rather than the exception.

3. Keep learning, openly, from mistakes & failure

I might be completely wrong along here. I might have diagnosed the wrong underlying illnesses from my postmortem, and drawn the wrong conclusions. However, we need to have these discussions and debates, out in the open, so that we can learn fast and well and move forward better. Over to you all. Thanks for reading.

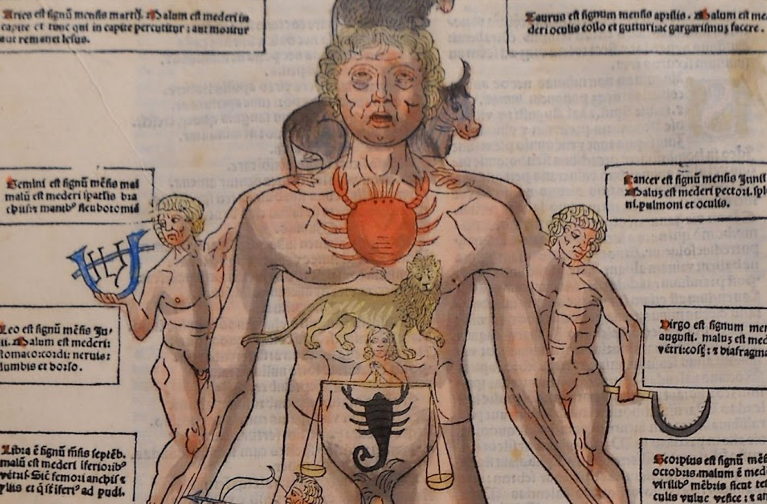

Teaser photo credit: Dubious anatomical science: Zodiac Man from Fasciculo di medicina by Johannes de Ketham, 1495 CE (via Moxham & Plaisant, 2014).