In the past year, concerns of civilizational collapse and unprecedented transformations of society and the economy have gone from being fringe ideas of eco-socialists to populating the mainstream debate in the Global North. The “Green New Deal” is gaining traction both amongst US Democrats and the UK’s Labour Party. There’s a growing desire for positive and visionary ideas, and a growing recognition of the scale and time frame of the challenge.

We can see the same desire in the explosion onto the scene of “Extinction Rebellion” and the phenomenal School Strike for Climate. While these initiatives represent different and internally diverse politics, they all speak to the same tendency: a profound sense of panic among people in the Global North.

There is much to praise and be heartened by in the shifting politics of the North, but there is a danger of missteps which could roll back the modest advances climate justice movements have made in the past few decades, and even contribute to the political forces we oppose. We need to debate the strategic value of the choices being made. We cannot afford to be uncritical, nor nihilistic.

What is urgency without equality?

For years, while climate justice movements fought to show climate change as a real and present danger resulting from a rigged economic system, and to build people power to change the system, NGOs from the global North used their superior access, resources, and media connections to call for pragmatism and reform.

But the breakdown of climate and other natural systems is occurring faster and with worse impacts than predicted, including in Europe and North America. And we are starting to see more urgency in the words of those same Northern NGOs and more coverage in the media generally.

The IPCC’s Special Report on the Global Warming of 1.5℃ broke through in the North, with newspapers carrying headlines like“12 years left to save the world” (although the report itself did not say that).

Amidst the resultant clamour for “climate action”, demands for “climate justice” have sometimes been drowned out. If mentioned, “climate justice” is usually divorced from the international context in which it was born, and stripped of its specific principles and demands, developed in democratic processes such as the World People’s Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth, that make climate change a question of justice rather than a quibble about emissions.

To her credit, Greta Thunberg does speak about equity, and is clear that the “sufferings of the many” in the South underwrite the “luxury of the few” in the North. She has said that to avoid the end of human civilization will require a massive overhaul of the dominant economic logic, and in particular the logic of consumerism that has developed over the past century in the North and is now being exported worldwide.

But her points in this regard are frequently overlooked and it is often only the urgency in her message that gets picked up. This is no fault of Greta. Rather, it is the fault of the global North’s mainstream NGOs who have conditioned mainstream media to ignore the need for just and systemic responses in favour of unhelpful, sensationalist “X years to save the world” headlines.

History shows us that far-right movements have experience in mobilising the idea of ecological preservation alongside nationalist exceptionalism. And a recent Buzzfeed exposé revealed how the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) had been willing get into bed with paramilitary human rights violators to help their vision of preserving an ahistorical and dehumanised “nature”.

With these tendencies in mind, it would be extremely irresponsible to demand an urgent and robust response to climate change without qualifications as to what kind of action is it to be carried out, on what terms, and by whom. We might feel a growing sense of panic but we need to keep cool heads. Declaring a state of ecological emergency can provide another excuse for making “tough choices” about who lives and who dies and who must sacrifice.

Others have pointed out how many countries, including the US, have been in a constant “state of emergency” for decades. As Casey Williams writes in The Outline:

“The history of such emergencies shows that they result in the expansion of repressive state power, short-circuiting political debate in favor of urgent, often militarized action to protect narrowly national interests, permitting governments to selfishly marginalize affected people even further.”

It may seem far-off, but we can already see, amid the clamour for climate action, support for dangerous distractions such as geoengineering and Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS). These unproven technologies are likely to profit corporations while hurting people, driving biodiversity loss, and contributing to chronic hunger. They are vigorously opposed by climate justice movements who point out that “net-zero emissions” as a demand leaves the door open to such false solutions and creates perverse incentives to carry on with extractivism as normal. The threat of the current moment is that we end up reinforcing a dangerous “action at any cost” dynamic.

System change not climate change

One of the slogans of the climate justice movement is “system change, not climate change” because climate change is but one expression of wider and deeper systemic issues which need addressing. Climate breakdown makes changing the system even more necessary of course.

The fight for climate justice is not only about cutting carbon emissions and other greenhouse gases, it is about the fundamental transformation of the systems that govern and underpin our lives.

The fossil fuel-dominated energy system leaves one billion people with little or no electricity. It’s not enough to change the fuel source of such a system. We need a people’s owned and controlled, decentralised energy system, based on sources of energy that are not only clean and renewable, but also safe. Though we might not want to grapple with this emergent reality, even large scale solar and wind rely on the extraction of materials, and sometimes the coercion and displacement of communities. So it’s time to rethink the entire system of producing and consuming energy, including the question of ownership.

Our current cruel food system is another a major source of greenhouse gas emissions – and it sees roughly one third of all food produced go to waste while close to a billion people go hungry each year.

Transport, housing and urban design are comparable in that they don’t actually serve the real needs of the majority of people while at the same time being incredibly polluting.

Our entire economic system fosters inequality between and within nations while exploiting natural resources in a manner and rate that is leading to ecological collapse. All these sectors must be radically restructured through a rapid, just transition to systems that serve the needs of peoples rather than profit.

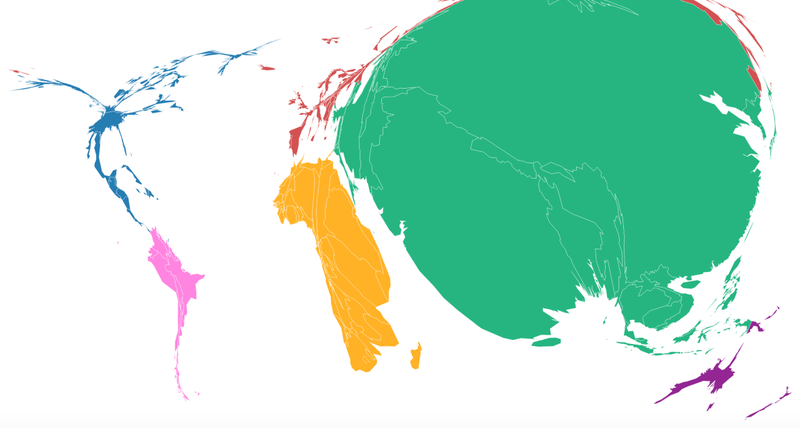

[Figure 1] Wealth and pollution: Country sizes show total GDP (2013), the sum of all the economic activity in each nation. The darker the shade, the higher the per capita emissions

[Figure 1] Wealth and pollution: Country sizes show total GDP (2013), the sum of all the economic activity in each nation. The darker the shade, the higher the per capita emissions

There’s not really any choice: we must live within the limits of local ecosystems and ultimately with the whole Earth system. We can’t just swap coal for solar and beef for soya and carry on with business as usual. A Green New Deal tied to economic growth is useless to us. As thinkers such as Jason Hickel constantly remind us, resources must be more fairly shared between the many and the few, while consumption itself must be scaled down.

Fundamentally we require different ways of relating to each other and the world, and many such alternatives already exist in the traditional knowledge of Indigenous Peoples, as well as in the sub-cultures and movements for alternatives of people living in industrial civilization.

It is important and encouraging that the new climate politics, embodied in the Green New Deal and School Strike for Climate, is not talking narrowly about “environmental” issues, but rather speaks as to many interrelated issues which cannot be addressed in isolation. After all, there are no environmental issues which are not also social issues, and vice versa.

The new climate politics must make no accommodation to those who seek to preserve the system intact, with either the fuel source changed, or some minor stops put on the most extreme vulgarities. The emperor has no clothes, as even striking school children now say, and no amount of fig leaves will make it otherwise.

The new emperors have come at the worst moment

The emperor may have no clothes, but there are a growing number of emperors. Some, such as Trump and Bolsonaro, have shown a disdain for climate policies, actions and international agreements and a lust for extractive industries which burn fossil fuels and deforest the planet.

For most of the world, climate chaos is a threatening pit, a death spiral. For snakes like Trump, Bolsonaro, and the Koch brothers it is a ladder of opportunity.

Climate breakdown will not only result in the death of a lot of people (predominantly poor people, in the global South) it will also reduce the ability of social movements to organise. And, as mentioned already, it may also end up providing justification for further authoritarian measures as things fall apart.

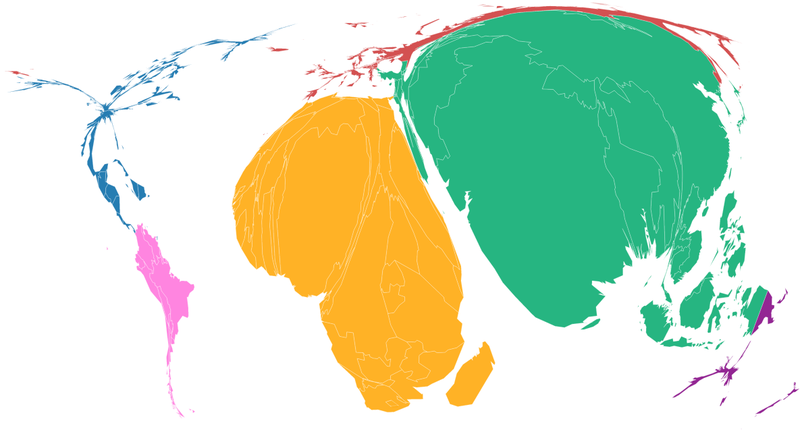

[Figure 2] Risk to climate change: country sizes show the number of people injured, left homeless, displaced or requiring emergency assistance due to floods, droughts or extreme temperatures in a typical year.

[Figure 2] Risk to climate change: country sizes show the number of people injured, left homeless, displaced or requiring emergency assistance due to floods, droughts or extreme temperatures in a typical year.

The risk is that at precisely the moment that the climate system begins to go completely haywire, the basis for sufficiently limiting the damage – international cooperation, long-term planning, government intervention in the economy, and a fair (re)distribution of resources – will be snatched out from under us. Global problems need global cooperation to solve.

The morality at the core of the Green New Deal – that the poor should not be forced to shoulder the burden of responsibility for cleaning up a mess caused mainly by the rich – is one of its central strengths after years of apolitical arguments for climate action.

Similarly, the argument used by the School Strikes – that future generations should not have to suffer because of the gluttonous overconsumption of previous generations – resonates thanks to its moral clarity.

But to advance climate justice, the moral argument at the heart of the newfound resurgent climate movement in the North must be extended into the international arena.

An end to empire – and the need for ‘reparations’

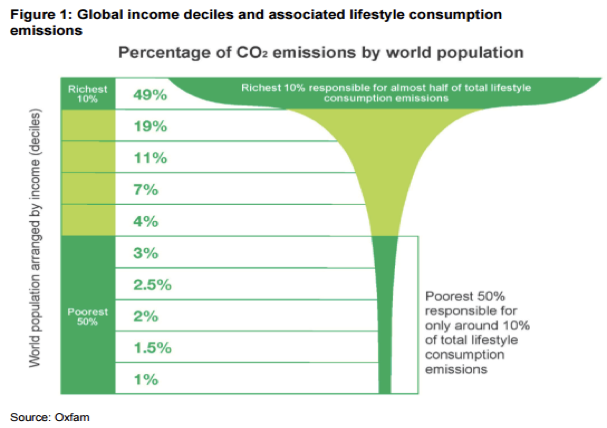

Fundamentally international climate politics is an argument about responsibility. The arithmetic of this responsibility is relatively simple. 100 companies are responsible for 70% of all emissions, 10% of the world’s population are responsible for 50% of emissions – overwhelmingly, living in the global North.

The U.S. has emitted 8 billion metric tonnes of carbon dioxide since 1850, more than any other country and more than most other countries combined. Its average annual carbon footprint is over 16 tonnes per person. An average individual in Mali produces less than a tenth of 1 tonne of carbon emissions.

Due to this historic overconsumption, from which their immense wealth is derived, Global North countries owe what climate justice movements have come to define as a “climate debt”. The debt is both for over polluting, and for denying the South the easy fossil fuel-based pathway of accruing capital.

Repaying the debt would involve rich countries doing their “fair share” of a collective global effort to stay below 1.5℃. But what does that mean, in the context of huge historical resource extraction by the rich countries? The truth is that even radical domestic policies by rich countries to cut emissions won’t, by themselves, do enough to stop climate chaos, unless the global South does more than its fair share.

[Figure 3] People living on less than $1.25/day

[Figure 3] People living on less than $1.25/day

Obviously this would be an unfair burden to place at the door of the nations of the South, so the excess must be covered with massive transfers (trillions rather than billions) of finance and technology from the North to the South. Whether we call it reparations or climate finance, the reality remains the same. It is not impossible – after all, there is always money for bailing out the banks or launching more wars – but convincing the populations of the global North that addressing climate change requires them to face up to the legacies of colonialism is not easy.

The main point here is not that reparations are required because they are the right thing to do. The point is that they are necessary to avert further breakdown of the planet’s natural systems. The transformations we need to make cannot be brought about without the countries of the Global South. And those countries cannot play their part if there is no finance, technology, and capacity to do so.

But if the North’s responsibilities are shirked again, if the American way of life is not up for negotiation, if the sound morality of the Green New Deal means eco-socialism for America and barbarism for the rest of the world, then the US completing its fair share is out of the question. And so is the possibility of a habitable earth.

Many proponents of the Green New Deal are very clear about its intra-national justice and equity dimensions. They correctly frame equity as non-negotiable and as the key to climate ambition rather than an obstacle. This is exactly the kind of attitude that the world urgently needs US-based groups to carry to the inter-national level.

It won’t be an easy task, given the US’s historic dedication to obstructionism, from the League of Nations, through Kyoto, to the Paris Agreement. The US government has always been anti-equity at home, and even more fervently anti-equity in its foreign policy. During international negotiations in 2011, Todd Stern (Obama’s Special Envoy on climate change) quipped “if equity’s in, we’re out”.

Such villainy has provided cover for other Global North countries to not only maintain their own fossil fuel addiction but continue forcing it on others. Collectively, they managed to complete a “great escape” from international law, before replacing that law altogether with an agreement – the Paris Agreement – that does not oblige Global North countries to do anything other than report on their own actions. The Agreement also explicitly absolves Global North countries of their liability for climate-related disasters. Unsurprisingly, the result is a world on course for 4℃ warming, and complete civilizational collapse.

Ultimately, a refusal by rich people and rich countries to reign themselves in even slightly is going to destroy the basis for life on earth. What makes refusal even sadder is that they wouldn’t even have to live like the global majority to massively reduce their footprint: as climate scientist Kevin Anderson often points out, if the richest 10% reduced their emissions to the levels of an average European (i.e. a totally comfortable lifestyle) global emissions would drop 30%. Or as an alliance of civil society groups put it: “If they were obliged to deliver their fair share of climate action, this alone would amount to 67-87% of the total 2030 mitigation requirements for 1.5℃”.

[Figure 5] Emissions inequality

[Figure 5] Emissions inequality

The power of collective, not the cult of celebrity

The past year has shown that there are new openings in the North for climate justice movements to advance system change. But for every opportunity there is a threat. A global movement for climate justice needs to be clear about which is which.

The prospect of rebalancing power between and within countries may seem like a remote one, but it’s been done before. Social movements in the South are capable of many things, from overthrowing colonial rule to ousting dictatorships and from ending apartheid to resisting privatization. They are not, however, capable of transforming the world system without strong, radical, and coherent movements in the North.

The devastating impacts of climate change are already raining down as we have seen across the globe; in Dominica, where a single hurricane caused damages worth 224% of the country’s GDP; in Mozambique, where a single storm destroyed 90% of a major port city; in India, where 60,000 farmer suicides have been linked to climate change; in Colombia, where worsening drought threatens to wipe out the Wayuu people; and in the Philippines, where many are still struggling to cope 5 years after Typhoon Haiyan.

There is no hope for a global climate justice movement if the majority of people in it are dealing with such impacts while the minority in the North are hamstrung by ideological constraints and business-as-usual modus operandi.

Movements in the North must therefore do more than simply repackage their existing efforts. Larger green NGOs are already rebranding, and attracting the funds for doing so, while perpetuating the same old, too little too late strategies of the past. To truly step up to the plate and play their part in a resurgent, ecologically-minded global justice movement, groups in the North will have to put meat on the bones of the system change slogan by articulating clear alternatives.

They will simultaneously have to reconnect with their legacies of international solidarity and build the power of the collective rather than the cult of celebrity in order to leverage the power of the state to limit corporate power. They have to be more ambitious than they’ve ever been – and this means being more committed to justice, for everyone, than ever before.

Teaser photo credit: By Julia Hawkins