International climate policymaking has failed to avoid a path of catastrophic global warming. Two often-overlooked causes of this failure are how climate-science knowledge has been produced and utilised by the United Nation’s twin climate bodies and how those organisations function.

It is now widely understood that human-induced climate change this century is an existential risk to human civilisation. Unless carbon emissions are rapidly reduced to zero, it is likely that global warming will either annihilate intelligent life or permanently and drastically curtail its potential.

While policymakers talk about holding warming to 1.5°C to 2°C above the pre-industrial level—a very unsafe goal given that dangerous climate-system tipping points are being activated now at just 1°C of warming—by their lack of action they are in fact setting Earth on a much higher warming path that will destroy many cities, nations and peoples, and many, if not most, species.

This cognitive dissonance was on full display at the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) twenty-fourth meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP24) in Katowice, Poland, last December. Speaking at COP24 to great fanfare and a standing ovation, Greta Thunberg, the 16-year old Swedish climate activist who has inspired a global movement for “climate strikes” by school students, called out the leadership failure of the COP adults who “are not mature enough to tell it like is”:

We have to speak clearly, no matter how uncomfortable that may be. You only speak of green eternal economic growth (and) about moving forward with the same bad ideas that got us into this mess, even when the only sensible thing to do is pull the emergency brake. You are not mature enough to tell it like is. Even that burden you leave to us children.

And then the adults got down to business, which was to write a rulebook for the Paris Agreement. The result does little to push nations to improve on the low ambition of the 2015 COP, and instead simply restates a request for nations to update their commitments by 2020.

The Paris deal established “bottom up”, voluntary, unenforceable, national emission-reduction commitments that would result in a warming path of 3.5°C, and closer to 5°C when the full range of climate-system feedbacks is taken into account. Such an outcome, say scientists, is inconsistent with the maintenance of human civilisation, and may reduce the human population to one billion people. Even the World Bank says it may be beyond adaptation.

In a foreword to the recent report What Lies Beneath: The Underestimation of Existential Climate Risk, eminent scientist and emeritus director of the Potsdam Institute John Schellnhuber warned that “climate change is now reaching the end-game, where very soon humanity must choose between taking unprecedented action, or accepting that it has been left too late and bear the consequences”.

In a recent interview, Schellnhuber said that if we continue down the present path “there is a very big risk that we will just end our civilisation. The human species will survive somehow but we will destroy almost everything we have built up over the last two thousand years”.

UN Framework Convention on Climate Change

Since the UNFCCC was established at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, annual human carbon-dioxide (CO2) emissions have increased more than 50 per cent, and there is no sign of their growth slowing. Since 1992, warming has risen from 0.6°C to 1.1°C, and the rate of warming is now accelerating, with Earth likely to hit the lower range of the Paris goal of 1.5°C within a decade or so. Evidence from Earth’s climate history suggests that the present CO2 level would raise sea levels by many tens of metres and the temperature by around a civilisation-ending 3.5°C in the longer term.

The UNFCCC strives “to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner”, but every year humanity’s ecological footprint becomes larger and less sustainable. Humanity now requires the biophysical capacity of 1.7 Earths annually as it rapidly chews up natural capital.

A fast, emergency-scale transition to a post–fossil fuel world is absolutely necessary to address climate change. But policymakers exclude emergency action from consideration because it is seen as too economically disruptive.

Two good examples of this mindset are found in the initial reports to their governments by Nicholas Stern (UK in 2006) and Ross Garnaut (Australia in 2008), in which they canvassed the 450 parts per million (ppm) and the 550 ppm CO2 targets. The figure of 550 ppm represents around 3°C of warming before carbon-cycle feedbacks are considered, and would be truly devastating for people and nature. While both Stern and Garnaut concluded that 450 ppm—around 2°C of warming without longer-term system feedbacks—would inflict significantly less damage, they nevertheless advocated that government start with the 550 ppm figure because they considered that the lower goal would be too economically disruptive. They have since acknowledged that evidence of accelerating climate impacts has rendered this approach dangerously complacent.

The UNFCCC orthodoxy is that there is time for an orderly economic transition within the current neoliberal paradigm, and so emphasis is placed on cost-optimal paths, which are narrowly defined. Policymakers increasingly rely on integrated assessment models (IAMs) that claim to provide economically efficient policy options, but their modelling of the physical science excludes materially relevant processes such as permafrost melting, and they systematically underestimate the cost and scope of future climate impacts.

Policymakers also favour commodifying carbon pollution and creating a vast market for the capture and underground storage of CO2, an unproven technology at scale but one that would create a boom for oil and gas producers. Unrealistic assumptions about untested solutions become an excuse for delaying strong action.

Policymakers, in their magical thinking, imagine a mitigation path of gradual change to be constructed over many decades in a growing, prosperous world. The world not imagined is the one that now exists: of looming financial instability; of a global crisis of political legitimacy; of climate-system non-linearities; and of a sustainability crisis that extends far beyond climate change to include all the fundamentals of human existence and most significant planetary boundaries (soils, potable water, oceans, the atmosphere, biodiversity, and so on).

The Paris Agreement is almost devoid of substantive language on the cause of human-induced climate change and contains no reference to “coal”, “oil”, “fracking”, “shale oil”, “fossil fuel” or “carbon dioxide”, nor to the words “zero”, “ban”, “prohibit” or “stop”. By way of comparison, the term “adaptation” occurs more than eighty times in thirty-one pages, though responsibility for forcing others to adapt is not mentioned, and both liability and compensation are explicitly excluded. The agreement has a goal but no firm action plan, and bureaucratic jargon abounds; the terms “enhance” and “capacity” appear more than fifty times each.

In a way, none of this should be surprising given the UNFCCC’s structure. The COPs are political fora, populated by professional diplomatic representatives of national governments, and subject to the diplomatic processes of negotiation, trade-offs and deals. The decision-making is inclusive (by consensus), making outcomes hostage to national interests and lowest-common-denominator politics.

This was again evident in Poland, where, in a deadly diplomatic strike, four big oil and gas producers—Saudi Arabia, the United States, Kuwait and Russia—blocked wording to welcome a scientific report on the 1.5°C target, which the COP had commissioned three years earlier in Paris. Such behaviour is a hallmark of COP meetings.

Discussion of what would be safe––less warming than we presently experience––is non-existent. If climate change is already dangerous, then by setting the 1.5°C to 2°C target, the UNFCCC process has abandoned its key goal of preventing “dangerous anthropogenic influence with the climate system”.

Moral hazard permeates official thinking, in that there is an incentive to ignore risk in the interests of political expediency. And so we have a policy failure of epic proportions.

Scientific reticence

The failure to appreciate and act to avoid the existential risk is in part due to the way climate-science knowledge is produced. The bulk of climate research has tended to underplay the existential risks, and has exhibited a preference for conservative projections and scholarly reticence, although increasing numbers of scientists—including Kevin Anderson, James Hansen, Michael E. Mann, Michael Oppenheimer, Naomi Oreskes, Stefan Rahmstorf, Eric Rignot and Will Steffen—have spoken out in recent years on the dangers of such an approach.

One study examined a number of past predictions made by climate scientists and found them to have been “conservative in their projections of the impacts of climate change” and that “at least some of the key attributes of global warming from increased atmospheric greenhouse gases have been under-predicted, particularly in Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessments of the physical science”. The authors concluded that climate scientists are not biased toward alarmism but rather the reverse of “erring on the side of least drama, whose causes may include adherence to the scientific norms of restraint, objectivity, skepticism, rationality, dispassion, and moderation”. This may cause scientists “to underpredict or downplay future climate changes”.

This tallies with Garnaut’s reflections on his experience in presenting two climate reports to the Australian government. Garnaut questioned whether climate research had a conservative “systematic bias” due to “scholarly reticence”, and observed that in the climate field this has been associated with “understatement of the risks”.

When dealing with existential climate risks, Schellnhuber has pointed to the limitations of methods that focus on risk and probability analyses that often exclude the outlier (lower-probability, high-impact) events and possibilities:

Experts tend to establish a peer world-view which becomes ever more rigid and focussed. Yet the crucial insights regarding the issue in question may lurk at the fringes. This is particularly true when the issue is the very survival of our civilisation, where conventional means of analysis may become useless.

He has pointed to a “probability obsession” in which scientists have tried to capture the complex, stochastic behaviour of an object by repeating the same experiment on that object many, many times:

“We must never forget that we are in a unique situation with no precise historic analogue. The level of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is now greater, and the Earth warmer, than human beings have ever experienced. And there are almost eight billion of us now living on this planet. So calculating probabilities makes little sense in the most critical instances, such as the methane-release dynamics in thawing permafrost areas or the potential failing of entire states in the climate crisis. Rather, we should identify possibilities, that is, potential developments in the planetary make-up that are consistent with the…conditions, the processes and the drivers we know.”

Kevin Anderson of the University of Manchester says there is “an endemic bias prevalent amongst many of those building emission scenarios to underplay the scale of the 2°C challenge. In several respects, the modelling community is actually self-censoring its research to conform to the dominant political and economic paradigm”.

A good example is the 1.5°C goal agreed to at the Paris December 2015 climate-policy conference. IPCC assessment reports until that time (and in conformity with the dominant policy paradigm) had not devoted any significant attention to 1.5°C emission-reduction scenarios or 1.5°C impacts, and the Paris delegates had to request the IPCC to do so as a matter of urgency. This is a clear case of the policy tail wagging the science-research dog.

|

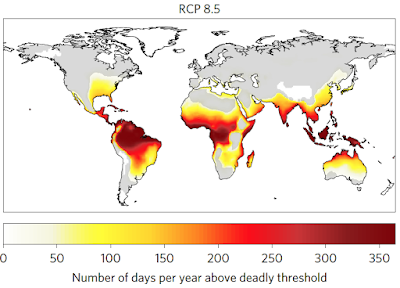

| On the current high-emissions scenario (RCP 8.5), most of the tropical zone experiences many months each year of deadly heat, beyond the capacity of humans to survive in the outdoors. Source: Global risk of deadly heat |

International climate policymaking has failed to avoid a path of catastrophic global warming. Two often-overlooked causes of this failure are how climate-science knowledge has been produced and utilised by the United Nation’s twin climate bodies and how those organisations function.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) produces science synthesis reports for the primary purpose of informing policymaking, specifically that of the UNFCCC. This may be termed “regulatory science” (as opposed to “research science”), which Sheila Jasanoff describes as one that “straddles the dividing line between science and policy” (9) as scientists and regulators try to provide answers to policy-relevant questions. In this engagement between science and politics, say Kate Dooley and co-authors, “science is seen neither as an objective truth, nor as only driven by social interests, but as being co-produced through the interaction of natural and social orders”.

This coproduction has resulted in a number of characteristic features in the work of the IPCC, and is exhibited in the way the organisation was formed in 1988. There was tension between the desire of UN member states for political control of the panel’s outcomes, and the need to have credible scientists in charge of an expert process of synthesising and reporting on climate science. Some countries, including the United States, were concerned that “the ozone negotiations had allowed experts to get too far ahead of political realities; they wanted to retain closer control over the production of scientific knowledge by appointing the Panel’s members”.

The compromise was that scientists would write the long synthesis reports, but that the shorter Summary for Policymakers would be subject to line-by-line veto by diplomats at plenary sessions. Historically, this method has worked to substantially water down the scientific findings. As well, government representatives have final authority over all actions, including the publication of all reports, and the appointment of the lead scientific authors for all reports. The latter has contributed to the reticent nature of much of the IPCC’s key work.

As early as the IPCC’s first report, in 1990, the US, Saudi and Russian delegations acted in “watering down the sense of the alarm in the wording, beefing up the aura of uncertainty”, according to Jeremy Leggett. Martin Parry of the UK Met Office, co-chair of an IPCC working group at the time, exposed the arguments between scientists and political officials over the 2007 Summary for Policymakers: “Governments don”t like numbers, so some numbers were brushed out of it”.

Like the UNFCCC, the IPCC process suffers from all the dangers of consensus building in a complex arena. IPCC reports, of necessity, do not always contain the latest available information, and consensus building can lead to “least drama”, lowest-common-denominator outcomes, which overlook critical issues. This is particularly the case with the “fat-tails” of probability distributions—that is, the high-impact but lower-probability events for which scientific knowledge is more limited.

Climate-model limitations

From the beginning the IPCC derived its understanding of climate from general climate models (GCMs) to the exclusion of other sources of knowledge. This had far-reaching consequences, including the IPCC’s reticence on key issues and incapacity to handle risk issues. Dooley has noted that for more than two decades researchers:

questioned the policy-usefulness of GCMs because of their limitations in dealing with uncertainty. They argued that the dominance of models—widely perceived as the “best science” available for climate policy input—leads to a technocratic policy orientation, which tends to obscure political choices that deserve wider debate. There is now an established body of literature critiquing the implications of this expert-led modelling approach to climate policy.

Dooley and co-authors say that research has now unmasked how this expert-led modelling approach to climate-policy politics gets built into science, enabling a technocratic and global framing of climate change, devoid of people and impacts.

There is a consistent pattern in the IPCC of presenting detailed, quantified (numerical) complex-modelling results, but then briefly noting more severe possibilities—such as feedbacks that the models do not account for—in a descriptive, non-quantified form. Sea levels, polar ice sheets and some carbon-cycle feedbacks are three examples. Because policymakers and the media are often drawn to headline numbers, this approach results in less attention being given to the most devastating, high-end, non-linear and difficult-to-quantify outcomes.

Twelve years ago, Oppenheimer and co-authors pointed out that consensus around numerical results can result in an understatement of the risks:

The emphasis on consensus in IPCC reports has put the spotlight on expected outcomes, which then become anchored via numerical estimates in the minds of policymakers…it is now equally important that policymakers understand the more extreme possibilities that consensus may exclude or downplay…given the anchoring that inevitably occurs around numerical values, the basis for quantitative uncertainty estimates provided must be broadened.

Oppenheimer and co-authors said that comparable weight should be given to evidence from Earth’s climate history, to more observationally based, less complex semi-empirical models and theoretical evidence of poorly understood phenomena. And they urged the IPCC to fully include “judgments from expert elicitations”—that is, what leading scientific figures think is going on when there is not yet sufficient, or sufficiently consistent, evidence to pass the peer-review process. This has not been done.

Getting risk wrong

We have already seen the consequences of scientific reticence and consensus policy-making in the underestimation of risk. IPCC reports have underplayed high-end possibilities and failed to assess risks in a balanced manner. Stern said of the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report: “Essentially it reported on a body of literature that had systematically and grossly underestimated the risks [and costs] of unmanaged climate change”.

This is a particular concern with climate-system tipping points—passing critical thresholds that result in step changes in the climate system—such as the polar ice sheets (and hence sea levels), and permafrost and other carbon stores, where the impacts of global warming are non-linear and difficult to model with current scientific knowledge.

Integral to this approach is the issue of the lower-probability, high-impact fat-tail risks, in which the likelihood of very large impacts is actually greater than would be expected under typical statistical assumptions. The fat-tail risks to humanity, which the tipping points represent, justify strong precautionary management. If climate policymaking is to be soundly based, a reframing of scientific research within an existential risk-management framework is now urgently required.

But this is not even on the radar of the UN’s climate bodies, which have given no attention to fat-tail risk analysis, and whose method of synthesising a wide range of research with divergent results emphasises the more frequent findings that tend to be towards the middle of the range of results.

A prudent risk-management approach means a tough and objective look at the real risks to which we are exposed, especially those high-end events whose consequences may be damaging beyond quantification, and which human civilisation as we know it would be lucky to survive. It is important to understand the potential of, and to plan for, the worst that can happen (and, hopefully, be pleasantly surprised if it doesn’t). Focusing on the most likely outcomes, and ignoring the more extreme possibilities, may result in an unexpected catastrophic event that we could, and should, have seen coming.

An upside to non-linearity?

The problem with non-linear changes in the climate system is that, almost by definition and given the current state of development of climate models, they are difficult to forecast. While Earth’s climate history can give valuable insights into our near future, the IPCC has downplayed, often to the point of ignoring, these important research findings on the range of possible climate futures.

This field of paleoclimatology has revealed that in the longer run each 1°C of warming will result in 10 to 20 metres of sea-level rise and that the current level of greenhouse gases is sufficient to produce warming that would likely end human civilisation as we know it by the destruction of coastal cities and settlements, the inundation of the world’s food-growing river deltas, warming sufficient to make most of the world’s tropical zone uninhabitable (including most of South, Southeast and East Asia), and the breakdown of order within and between nations.

We have physical, non-linear climate-system disruptions coming very soon. But there are also social, economic and psychological tipping points that could trigger a much more rapid response to climate change. The rapid rise in popular support in the United States for the Green New Deal championed by the newly elected congresswoman from the Bronx, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, may be one such moment.

Big changes, says Schellnhuber, will require us to “identify a portfolio of options…disruptive innovations, self-amplifying innovations”. He says that these cannot be predicted precisely, so we need to look into whether there are high nonlinear potentials in a whole range of emerging technologies.

Such innovation is an important element for any whole-of-society, government-driven approach, such as the Green New Deal and its proposal for a wartime-level effort to build a zero-emissions economy, with an emphasis on jobs and justice.

Schellnhuber says the problem is the conventional economist who “will want to be efficient, but efficiency is the enemy of innovation”. Rapid innovation at a time of crisis, when time is short, means parallel innovation as you look for many answers at the same time, and some will fail, and capital will be wasted, but the successes are the “change we need”.

He says we must now muster climate-change venture capital at a global scale because “we cannot efficiently get ourselves out of this predicament”. This means:

We have to save the world but we have to save it in a muddled way, in a chaotic way, and also in a costly way. That is the bottom line, if you want to do it in an [economically] optimal way, you will fail.

Such thinking would require a revolution in the neoliberal norms of the UNFCCC. Perhaps that is not possible and the body can no longer serve a useful role. Developing mechanisms that are more fit for purpose is now an urgent task.

This article was first published by Arena Magazine.