Nearly 1.5m students around the world walked out of school on March 15 2019 to protest about the failure of the world’s governments to tackle climate change. The young climate strikers are forcing climate change onto the news agenda but researchers have warned that without a way to mobilise their passion in the long-term, the momentum they’ve generated for climate action could be lost.

In this first issue of Imagine, we asked academics how the strikes can translate into long-term impact. One researcher proposes directly channelling the energy of young people into climate action with a national service for the environment. Others tell us how youth enthusiasm can play an integral part in changing climate policy around the world – and what it all means for tackling this huge issue.

What is Imagine?

Imagine is a newsletter from The Conversation that presents a vision of a world acting on climate change. Drawing on the collective wisdom of academics in fields from anthropology and zoology to technology and psychology, it investigates the many ways life on Earth could be made fairer and more fulfilling by taking radical action on climate change.

You are currently reading the web version of the first issue. Here’s how this issue appears when sent to your inbox. To get new issues delivered straight to your inbox, subscribe now.

Climate change and the state of the planet in three graphs

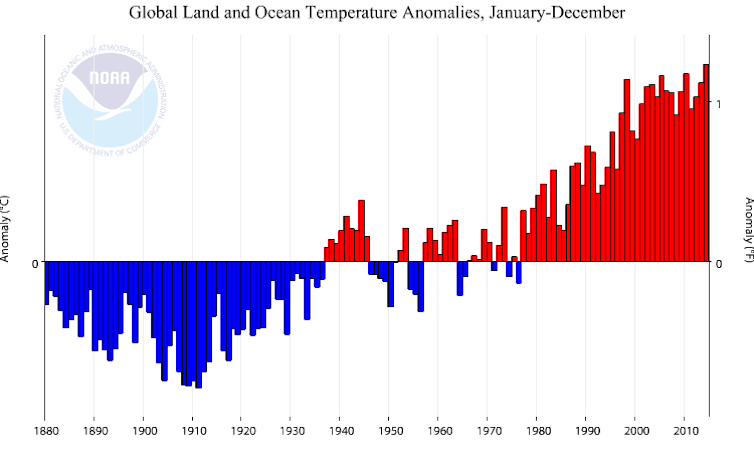

1. Global temperatures are on the rise.

Temperature history for every year from 1880-2014. NOAA National Climatic Data Center

2. The US bears an “extraordinary responsibility to respond to the climate crisis”, says D.T. Cochrane, Lecturer in Business and Society at York University, Canada. The country produces an “excessive amount of emissions” and has an unequal share of resources.

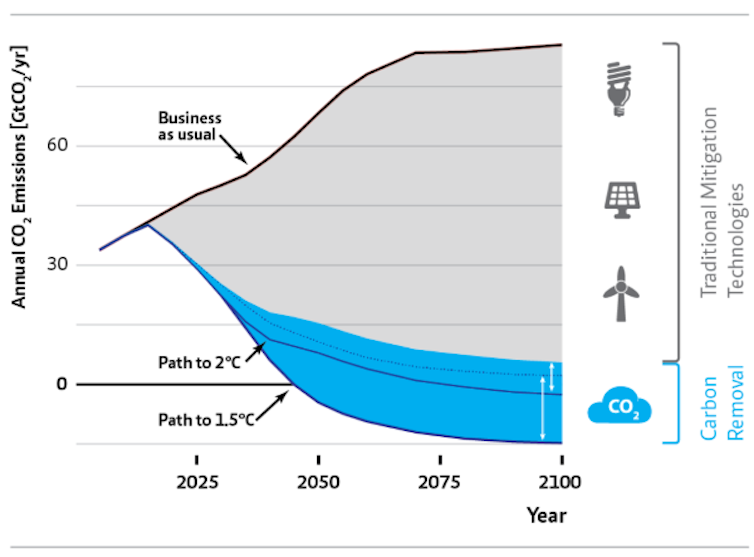

3. Business as usual is not an option.

A national service for the environment

Michelle Bloor, Principal Lecturer and Environmental Programme Manager at University of Portsmouth, argues that a volunteer force of conservationists could offer experience and training to young people and ensure there are eager applicants for the vital work of helping the world’s species and habitats most threatened by climate change.

Young people could get on the act straightaway, from replanting mangrove swamps in Vietnam and helping reintroduce beavers in Scotland to measuring coastal pollution in Senegal.

Bloor groups the work a national service for the environment could cover into four categories:

- Data collection – by surveying wildlife abundance or measuring water quality in lakes and rivers, volunteers could help scientists understand how ecosystems are changing.

- Green construction – restoring wooded habitat could absorb carbon and create corridors which connect pockets of wildlife in fragmented habitats. Large-scale construction projects could involve volunteers working on habitat highways – green corridors which help wildlife cross road networks.

- Species reintroduction – helping ecosystem engineers, such as beavers, return could help the process of expanding natural habitats. These animal recruits could create new dams and lakes, which provide new opportunities for more species to thrive.

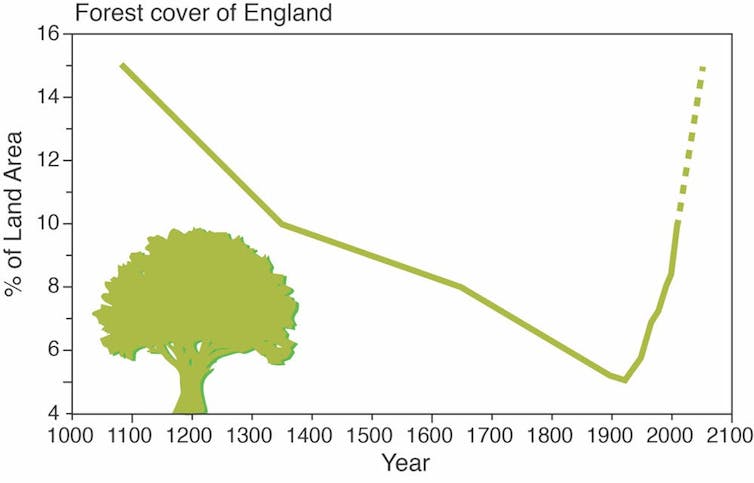

- Reforestation – humans have cut down three trillion trees since the dawn of agriculture – around half the trees on Earth. A mass reforestation effort would need plenty of volunteers worldwide, something a youth volunteer force could supply. In the UK, increasing total forest cover to 18% could soak up one third of the required carbon emission cuts needed by 2050, according to the 2008 Climate Change Act.

Change in the forest and woodland cover of England over the last 1,000 years.DEFRA, Author provided

Read more:

National service for the environment – what an army of young conservationists could achieve

A conservation army of millions was active in 1930s America

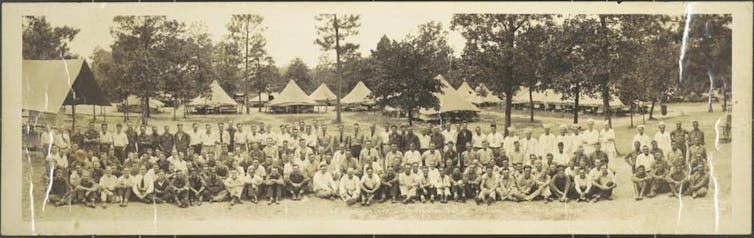

The idea of enlisting millions of young people in conservation work is not new. It has origins in a public work relief programme from the 1930s. During the depths of the Great Depression and while the Dust Bowl ravaged rural America, US president Franklin Roosevelt implemented a series of reforms as part of the New Deal to implement a more sustainable land policy and revive economic growth. One of those reforms was the creation of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). It enlisted 3m young men who planted over two billion trees on more than 40m acres of land between 1933 and 1942. Their aim was to repair ecosystems throughout the US with hundreds of projects in forestry and conservation.

A company of CCC youths in Texas, 1933, with segregated African American volunteers on the far right, University of North Texas Libraries, CC BY-ND

A national service for the environment would see individuals taking a direct role in mitigating climate change, but there is also an emerging political project aiming to capitalise on public support for action.

Radical climate action is now a feature of mainstream politics

The Green New Deal – an ideological heir to Roosevelt’s plan – is energising debate on climate action in the US. Endorsed by Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and numerous 2020 presidential candidates, the Green New Deal is a plan to enact a “green transition” in society and the economy within the next ten years. The idea has attracted worldwide attention, including in the UK, where members of the Labour Party are urging the party’s leadership to adopt a similar plan as policy.

What is the Green New Deal?

The Green New Deal is a proposed series of reforms with three broad aims:

- To eliminate greenhouse gas emissions from energy, transport, manufacturing and other sectors of the economy within ten years.

- To create full employment in the manufacture of clean energy infrastructure and other essential work.

- To redistribute wealth and tackle social and economic inequality.

Rebecca Willis, Researcher in Environmental Policy and Politics at Lancaster University says:

Alongside an aim for net-zero greenhouse gas emissions and 100% renewable energy, the Green New Deal demands job creation in manufacturing, economic justice for the poor and minorities, and even universal healthcare through a ten-year “national mobilisation”, which echoes president Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal in the 1930s.

Read more:

The Green New Deal is already changing the terms of the climate action debate

Decarbonisation to become a zero-carbon society

What would decarbonisation involve? The Green New Deal entails shifting electricity generation from coal and natural gas to wind, solar, hydroelectric and other zero-carbon technologies.

- Cars and trucks running on petrol and diesel would likely need replacing with mass public transport options powered by green energy.

- Private vehicles would need to use batteries or hydrogen fuel cells.

- Air travel would also need to use electricity for short flights and advanced zero-carbon fuels for longer journeys.

- Electric heating in our homes, schools and places of work.

The decarbonisation process may require an emergency mobilisation effort akin to that seen in World War II. Because, according to Kyla Tienhaara, Canada Research Chair in Economy and Environment at Queen’s University, Ontario, the scale and speed of decarbonisation needed today cannot be delivered by carbon taxes alone:

The carbon price has to be incredibly high and cover a broad swathe of the economy to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Governments haven’t shown a willingness to do this and recent research suggests that even steep prices will not produce the deep emissions reductions required to limit global warming to under 2°C.

Read more:

America can afford a Green New Deal – here’s how

Will people lose jobs because of the Green New Deal?

The Green New Deal resolution guarantees full employment, but Fabian Schuppert, Lecturer in International Political Theory and Philosophy at Queens University Belfast, believes its promised changes to the economy would have immediate consequences for workers in many industries which rely on fossil fuels.

Job losses in sectors such as coal mining and manufacturing could erode popular support for a Green New Deal and harm the plan’s commitment to a just transition, he argues. A just transition is a commitment to ensure the costs of a transition from fossil fuels – such as tax rises and redundancies – aren’t forced on working people.

Schuppert suggests that introducing a universal basic income – a guaranteed payment to everyone in society without means-testing – would help cushion the initial shock of a green transition by providing people with support while they look for new jobs or training. In the long run, he argues, it could have broader social effects:

A universal basic income might offer citizens time to engage in fulfilling community-based work that doesn’t generate profit but which has social value. Taking them out of their cars in long lines of commuter traffic and putting them in allotments growing food or in parks enjoying nature could help usher a whole new way of life.

Read more:

Green New Deal: universal basic income could make green transition feasible

Does the US have the money for a Green New Deal?

This is arguably the question most often asked of the Green New Deal. Edward Barbier, Professor of Economics at Colorado State University, says it does and has some suggestions:

- Pass a carbon tax which will help raise money to pay for a transition to a green economy and also help spur that very change.

Passing a carbon tax is one of the best ways to go. A US$20 tax per metric ton of carbon that climbs over time at a pace slightly higher than inflation would raise around US$96 billion in revenue each year – covering just under half the estimated cost. At the same time, it would reduce carbon emissions by 11.1 billion metric tons through 2030.

- Redirect subsidies currently given to fossil fuel companies. Those subsidies are estimated to be around US$5 trillion a year globally, 6.5% of global GDP.

- Raise taxes on the highest-earning Americans.

Imposing a 70% tax on earnings of US$10m or more would bring in an additional US$72 billion a year …

Read more:

America can afford a Green New Deal – here’s how

In an article for CNN, economist Jeffrey Sachs of Columbia University also argued that the Green New Deal is “feasible and affordable”.

But climate justice is still a grey area with the Green New Deal

While one of the central aims of the Green New Deal is to redistribute wealth and tackle social and economic inequality in the US, its impact on poorer parts of the world has perhaps been less discussed.

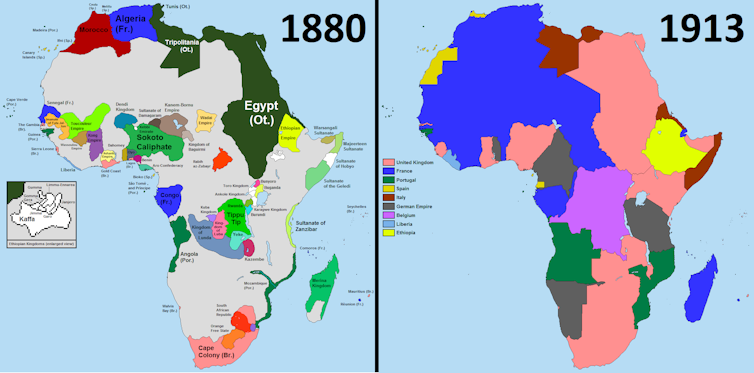

Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò, Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Georgetown University, says that climate justice must not end at the borders of a country implementing a Green New Deal. Otherwise, he states, the Green New Deal may become “the next chapter in a long history of US industrial policies that have oppressed people”.

Táíwò believes there is a risk that a Green New Deal could spark a race for vast territory on which to build solar farms or grow biofuel crops. In the process, historic injustices could be perpetuated through “climate colonialism”. He says:

A research institute reported in 2014 that Norwegian companies’ quest to buy and conserve forest land in East Africa to use as carbon offsets came at the cost of forced evictions and food scarcity for thousands of Ugandans, Mozambicans and Tanzanians. The Green New Deal could encourage exactly this kind of political trade-off.

Read more:

How a Green New Deal could exploit developing countries

The contradiction at the heart of the Green New Deal

Matthew Paterson, Professor of International Politics at Manchester University says that new infrastructure and redistribution proposed by the Green New Deal may boost carbon emissions:

Many of the measures proposed – such as investing in infrastructure and spreading wealth more evenly – will intrinsically work in tension with efforts to decarbonise the economy. They create dynamics that increase energy use at the same time as other parts of the Green New Deal are trying to reduce it. For example, building infrastructure such as new road networks will both create demand for carbon-intensive cement manufacture and opportunities for more people to travel by car.

Other academics like Joe Herbert, a researcher at Newcastle University, have argued that sustaining emission reductions in the long term can only be achieved by managed degrowth of the economy.

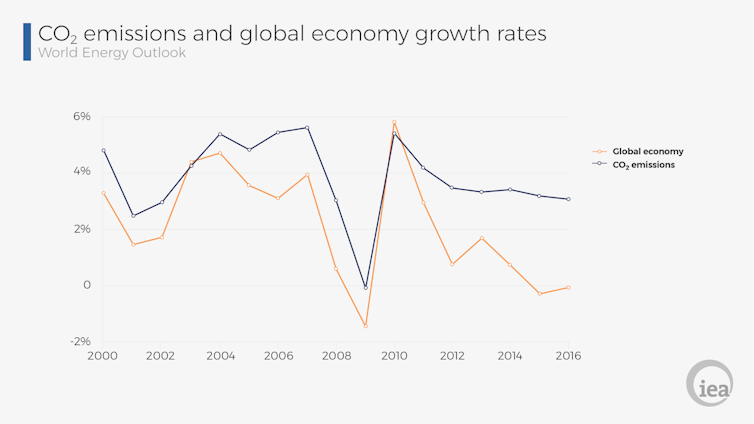

Economic growth and carbon emissions are tightly linked. International Energy Agency

As the Green New Deal develops and its policy details are refined, its proponents may choose to adopt such novel ideas.

A national service for the environment in a Green New Deal

At such an early stage in the Green New Deal’s development as a political project, much of the discussion around it remains speculative. However, Rebecca Wills argues that it has already achieved something by reinvigorating the debate over climate action:

The Green New Deal is already succeeding in putting climate action where it belongs, as the defining political issue of our time. How strange that we have the current US political environment to thank for this huge step forward.

Read more:

The Green New Deal is already changing the terms of the climate action debate

Michelle Bloor believes that including her vision of a national service for fighting climate change within the aims of a Green New Deal could help galvanise support for the latter, by providing an outlet for some of the enthusiasm of young people who have taken part in the climate strikes. Building a coalition for radical climate action under the Green New Deal is likely to lead the ongoing strategy of the project. Bloor believes that mobilising the growing youth movement is a good place to start.

Further reading

- The three-minute story of 800,000 years of climate change

- How humans derailed the Earth’s climate in just 160 years

- Why fear and anger are rational responses to climate change

- Fossil fuels are bad for your health and harmful in many ways besides climate change

Click here to subscribe to Imagine. Climate change is inevitable. Our response to it isn’t.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.