Five years ago my wife, Ann-Helen, and I bought this small farm, Sunnansjö, in Sweden, some 30 km east of Uppsala. I have all my life been keen on growing vegetables and lately my interest has been more into trees and perennial plants. So the main idea was to use most of the land for such crops.

But a place has its own conditions, its own genius, as expressed by Wes Jacksson. Most our lands are wet and heavy, prone to floods. For me, having farmed for more than thirty years on light sandy soils, where water was almost always short in supply, it was a shock to realize that I knew almost nothing that was relevant for our new farm. Mud and water were all over the place, all over me.

Slowly, we began adjusting our plans to reality, to the local conditions, opportunities and limitations, I had to rethink my role from grower to ecosystem manager. The real treat of our land is that is so varied. We own a long stretch of the shore of a lake, there are rich wetlands, peat bogs, meadows, old growth forests and many fields with what we call ”field islands” in Swedish, i.e. bigger rocky patches with scattered trees in the fields. Overall, we have a lot of ecotone zones (edges, borders) between the various biomes, and such border zones are often very rich in diversity and productive in their own way. Our mission now on the farm is to manage and enhance all those transition zones.

For sure, some fields which are a bit higher and sloping, we ditched and drained for intensive horticulture, including a green house. Other fields we have planted with tree crops, mostly apples and hazel nuts and we grow crops in between the trees while they are small.

When we moved in, we could hardly see the lake. Looking at old maps and even aerial photos we could observe that the landscape was much more open some 60 years ago. Like all farms at that time, they had cows here, and the cows were grazing a lot, even in the forest. Gradually we realized that we needed companions in our landscape management. For sure, we could use some more hands here, but what we really needed where quadrupeds to graze the meadows, the wetlands and many of the border zones. We settled for cattle some three years ago, and gradually we are transforming the landscape together. Admittedly, it is not only for ecosystem functions we opted for grazing, to have an open parkland (pastoral in its true sense) landscape to live in is esthetically appealing. And yes, we will get some meat and tallow as well; the first animal was slaughtered last fall.

Learning to know each other (the cows and us) and see how we together shape the farm made us think more about cows and cow-man interaction and dependency.

In media there is a binary debate about cows. They destroy the climate or they maintain precious grasslands, they are resource wasters or resource enhancers, their meat is deadly or healthy.

My friend Chris Willie, long time engaged in the Rainforest Alliance and the Sustainable Agriculture Network call cattle “eco-destruction machines” and he tells me that that grazing is the leading cause of species destruction in the US West. Still, he doesn’t advocate cow eradication but engages in the Grassland Alliance, that support grazing operations that protect the environment and public health; maintain high animal welfare; and treat ranchers, farmers, and workers fairly.

Reality is not black and white and a lot of it depends on how we manage the cows. Industrial farming practices, including feed lots and the feeding of grain and soy to dairy cattle, have changed the ecological role of the cow and it has also changed the way people see cows. Farmers are told to run their farms as businesses and to lower costs or increase productivity again and again. Many consumers have lost the connection with farms and farm animals and see livestock rearing as a brutal and unethical activity. And of course, industrial farming is confirming and aggravating that impression. To some extent, industrial agriculture and vegans share the same view on why we have cows: they are only kept to be exploited.

But then there are millions of farmers who keep their animals in a good way, both ethically and environmentally. They are sticking to the old contract between man and cattle, a contract which benefitted both. An extremely successful partnership. Some would even say too successful as cattle and humans together are totally dominating the mammal planetary zoo, leaving little space to other species. In the case of Sweden, despite a doubling of human population in hundred years there is only a third of the number of cows compared to the peak in the 1930s. Meanwhile, the number of elks and deer have expanded their numbers to be bigger than in many hundred years. In Sweden, loss of semi-natural grassland is the major threat to biodiversity these days.

Rarely are cows discussed as cultural beings and human – cattle interaction with the perspective multi-species organization. We have not only bred cattle and farmed plants to suit our needs, we have also shaped whole cultures and landscapes according to the needs of those animals and plants. And they have shaped us, body and soul. And cattle perhaps more than any other domesticated organism (in competition with rice). All the early civilizations had some kind of cow or bull gods or myths. In the Norse creation myth, the cow Audhumla even created the giant and the gods.

By having those cows, interacting with them, see how they interact with each other and with the landscape, we realized that there is a story to be told. A story about the co-evolution of man, cows’ landscape, culture and society. We are now busy writing that story, which will be published (in Swedish) early 2020.

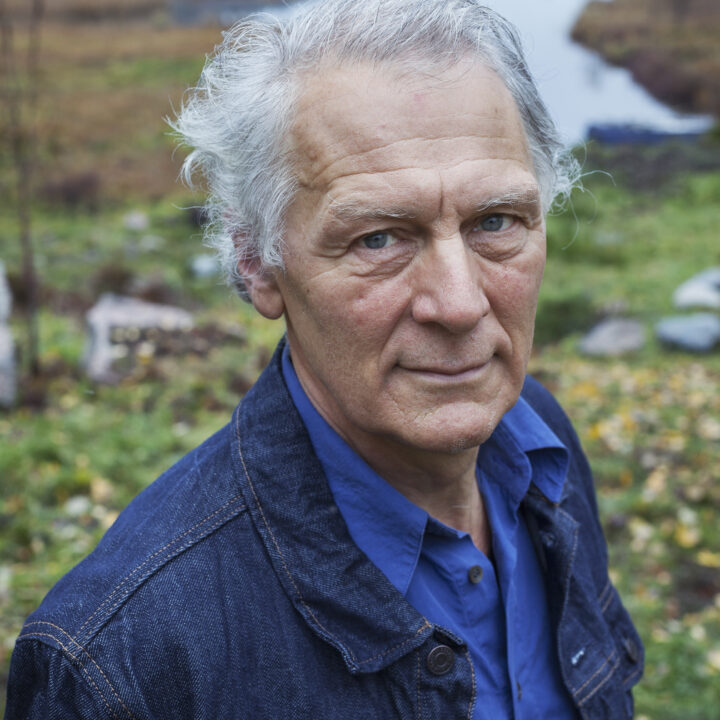

Teaser photo credit: By Jorchr – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0