Ed. note: This is a largely rewritten version of a post by Wayne that was published on Resilience.org in 2017 here.

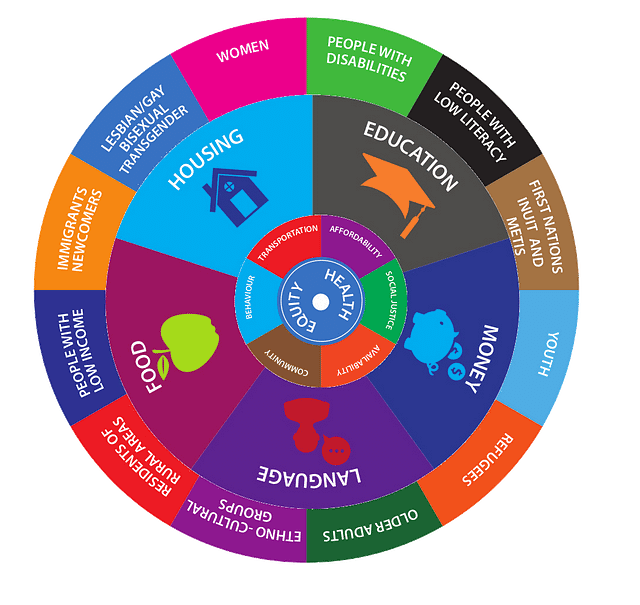

This graphic of the circle of life and health determinants, prepared by Ontario’s Grey Bruce public health team, highlights the role of food. Unfortunately, this appreciation of food’s importance is not the norm in the school of health policy analysis known as “the social determinants of health.” A new book may provide an opportunity to link food to other social determinants.

Everyone has heard about the 1 percent, and even the one percent of the one percent. But who knows what such concentration of wealth and power means for the health and well-being of the 99 percent? Or where food fits in that picture? Here’s an intro to some of the newest and best research, along with some critical remarks based on my 25 years as a healthy food advocate.

A new book on health equity in an inequitable world, a central requirement of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

Two years ago, Arne Ruckert and Ronald Labonte wrote a brief, easy-to-read, and richly-documented review of global evidence on the health impacts of widening economic inequalities over the last decade. Labonte has long been a leading contributor to the field of social determinants of health. Now the two have a new book, published by Oxford University Press. It expands on their earlier article. (Link to their new book here, and keep up with the listserv serving SDOH practitioners here.)

Since 2008 — a year of living dangerously for financial institutions, economic stability, runaway food prices, and political instability — the ground rules of public policy and community well-being have been shaken to the core. The year 2008 is starting to look like a year of shock therapy, to use Naomi Klein’s phrase, which was followed by very rough rehab imposed by a triple whammy of neoliberalism (deregulation and privatization of former government tasks), austerity (budget cuts to conventional social expenditures), and technological change (causing the disappearance of secure and middle-income jobs). The way these momentous policy shifts went down so quickly in so many places is a forceful reminder of the high-speed, globalized and interconnected world we live in. The crisis was too great for powerful forces to waste, perhaps, and global health has paid the price.

Ruckert and Labonte add a useful term to the analysis of linkages between economic and health inequalities. They talk about pathways for disease, and how these pathways were widened by the amalgam of neoliberalism, austerity, and technological unemployment.

They deserve praise for the breadth of their research and their notion of pathways. But I do regret (yes, I am a broken record) that the authors neglect the critically important role played by food systems and the rapid rise of hyper-processing in the global food industry.

In my view, hyper-processed or ultra-processed foods have had hurricane force impact on mainstream diets in Noth America since the 1990s. The processing trend has gathered force globally since about 2008. This deep-going change to diet composition, together with the meal experiences that go with industrialized food, deserves attention as a determinant of illness. It has importance as a cause and pathway for diseases on par with deregulation, austerity and technological unemployment.

Food is a biological necessity for both physical and social well-being. Humans are classified as social animals partly because they have always produced, prepared, and eaten food together. Because food is so social, the health impacts of food should be highlighted as both a social determinant of health in its own right and as a pathway for other social determinants (low income, for example).

People hungry for both macro- and micro-nutrients will, almost by definition, miss out on key ingredients of active and healthy lives (for one U.S. example, see here). As well, research shows, eating too much hyper-processed food or “junk food” is almost as harmful to body, mind, and soul as eating too few nutrients and calories.

It might seem like a bit of a stretch to add being loneliness to the mix of neoliberal illnesses — people have suffered from loneliness long before some coldhearted conservative thought to call himself a neoliberal. But neoliberalism is an ideology at odds with any notion of “all for one and one for all.” It’s all about being on your own — you are your own job security and your own food security. As to the impacts of wealth, we all know the blues classic about nobody loves you when you’re down and out. It’s lonely at the bottom.

In an economy where companies cut costs by having customers serve themselves through their home computer — no need to go shopping with a friend when you can keep shopping by yourself — we are truly in the era of the lonely crowd. Food is heading in the same direction. Lonely people are unable to benefit from chance companionship (the word itself derives from the Latin roots for with and bread) and conviviality when a person is invited to join others for a meal or snack.

Loneliness is increasingly understood to be at risk for a wide range of health disorders. Indeed, loneliness is said to rival the negative health impacts of heavy smoking. Lonely people are unable to benefit from the companionship (the word itself derives from the Latin roots for with and bread) and conviviality associated with meals with others. A food system prioritizing grab-and-go and heat-and-eat convenience can lead to eating alone, a disturbing trend of the past decade (as suggested here and here). It can’t be good for digestion or social support that some 40 percent of lunches are eaten alone at a desk, while about 20 percent of meals are eaten in a car (as reported here and here).

We are looking now at a food system that has lost its evolutionary mooring. In the past, food nudged, sculpted, fulfilled, and reaffirmed what it means to be human. This can no longer be assumed. That’s why I developed the term “people-centered food policy” — to focus on the historic people-serving function of food that we are now at risk of losing. The presence or loss of a people focus to food is the presence or loss of a major existential determinant of what it means to thrive as humans.

Unfortunately, as with most proponents of the “social determinants of health,” Ruckert and Labonte don’t make much of the determining role of food.

WHY HEALTH INEQUITIES ARE OVERLOOKED

Income inequality gets a lot of media attention because of the shocking contrast between a few people hoarding so much wealth while so many people have so little money.

But the popular resentment of greed doesn’t automatically extend to empathy for the health problems of poor and working people. That’s because of a mindset as harmful in its own way as neoliberalism. This mindset blames the rise of chronic diseases on poor personal lifestyle choices, not poor incomes. As a consequence of this mindset, the increasingly inequitable gap in health and longevity between rich and poor isn’t viewed as much of a scandal as vastly different income levels.

Despite the lack of public instinct about health and income, many public health analysts pay a lot of attention to the relationship between income and health. Food planning professor Lesli Hoey at the University of Michigan has a great way of putting it: “the postal code is more important to disease patterns than the genetic code,” she says.

There’s a simple reason why health planners attach so much importance to income as a major cause of disease. Diseases that can be attributed to low income are easier and cheaper to remedy than disease burdens caused by genetic inheritance or deeply-embedded lifestyles. The promise of health promotion and disease prevention is to avoid three costly problems — unnecessary suffering, unnecessary expenditures for costly medical interventions, and avoidable costs of lost work time due to post-operation healing and recovery.

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, as the old saying goes. That folk wisdom has the cost ratio of prevention to cure about right.

Health planners also hope that the enormous savings from disease prevention will appeal to people who keep watch on government expenditures — because so many of the runaway costs of treating chronic diseases are borne by taxpayers. Much of the money saved from a prevention-based strategy is public money that could be freed up for more productive expenditures. There’s a huge “opportunity cost,” as well as a price in human pain, to doing nothing.

That’s why Ruckert’s and Labonte’s work to track the source of health inequities in the economy is an important public service.

WHY GOVERNMENTS LACK MONEY

One pathway to disease is tax evasion, which reduces the ability of governments to fund programs that can overcome the inequities of the marketplace. In the neoliberal era, government tax rates have led to “competitive austerity,” as governments compete to offer the lowest taxes to investors — a race to the bottom instead of the top.

According to the authors, the global losses from tax reduction for the rich and tax evasion by the rich jumped from US$28 trillion in 2004 to US$58 trillion in 2012. That’s a big jump, done in record time, setting the stage perfectly for the austerity campaign launched shortly after the big banks were rescued with billions in public money. (For the salacious details, check this.)

What governments giveth with the right hand, they taketh from social programs once funded with the left hand.

Ruckert and Labonte identify the following pathways as most important throughout the world: reductions in freely-available health services, including food formerly provided as one of these services; rising unemployment; rising homelessness; declining protection of vulnerable workers (aka the rise of the precariat); welfare reforms that have masked cuts in services.

They take care to note how each of these pathways damages both the physical and mental health of disadvantaged people. I think this linking of physical and mental health is a very important addition to the ways impacts of cutbacks are measured.

THE PATHWAY NOT TAKEN

The pathway to ill health that’s overlooked, in my view, is the dominant food system — a major beneficiary of unfortunate neoliberal, austerity and technology trends.

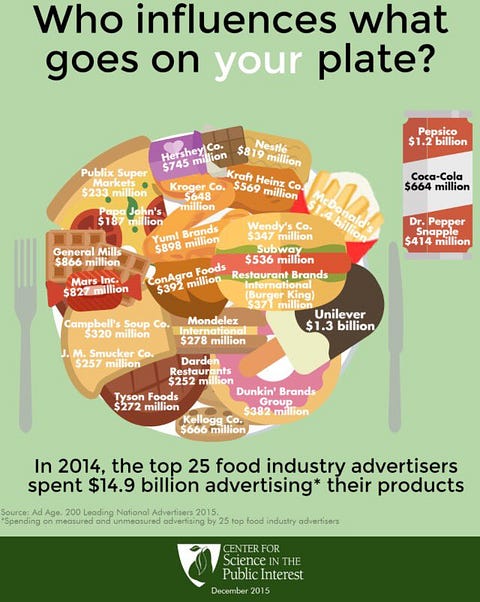

According to one medical journal, governments spending to promote healthy foods are outgunned 30 to 1 by corporate advertising of questionable foods.

Big Food has been a major beneficiary of neoliberal-inspired deregulation and unwillingness of governments to regulate. Despite overwhelming evidence on the harm done by excessive salt, sugar, and trans-fats, there’s little in the way of barriers to the companies that heavily promote products plastered with these ingredients. The absence of governments prepared to fulfill their duties to care for and protect their citizens almost warrants the description of “failed states.”

If ever there was a pathway to disease, failure to protect the population from saturation advertising of massively adulterated food is one. Even though this abuse testifies to concentrated wealth and power, the authors fail to give such abuse of food functions the recognition it deserves.

Nor, on the positive side of food possibilities, do the authors identify the potential of the popular sector to establish the conviviality, support, empowerment, and agency that are critical to resilience and health. Such traditions have certainly been the mainstays of popular health (rude health, as it was known) over centuries, long before the rise of the modern healthcare systems.

Two scholars who don’t miss the power lines linking Big Government and Big Food are Hilary Seligman and Dean Schillinger, authors of an important article on hunger and social disparities in the July 2010 edition of the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine. Their evidence shows that the price gap favoring cheap unhealthy foods over more expensive healthy foods has “widened over the past two decades.”

Seligman and Schillinger also describe how poverty, food security, seeming “poor self-control” and diabetes work in lock-step. “Adults with diabetes are 40 % more likely to have poor glycemic control if they have inadequate money for food than if they can afford a healthy diet,” they write.

To be fair, Labonte has written several items elsewhere — see here, for example — on how food fits in the neoliberal playbook. Maybe it’s the social determinants of health framework that leads to his downgrading of food system issues?

The brief article preceding the book’s publication concludes with a reference to the Sustainable Development Goals adopted by the United Nations in 2015, a highwater mark for acceptance of progressive social policy internationally. They refer to the totality of SDG goals as “a compelling anti-austerity agenda.” I agree. We should all do more to promote awareness of these goals — a positive alternative to what governments are now doing.

(For more of Wayne’s posts on cities and food, please subscribe to his e-newsletter at http://bit.ly/OpportunCity)