Translated by Adrián Beling and Ana Estefanía Carballo

Latin America currently confronts different types of crises. The social and the ecological question appear as two central problems, which will be determining not only of the region’s future, but that of the whole of humanity as well. The difficulty to address these problems lies in the fact that, up until today, almost all responses directed to address social issues – such as poverty, informal employment or inequality – are oriented to economic growth. These includes the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with which the United Nations promotes a global scheme to confront the biggest challenges of the 21st century. However, at the same time, there is no doubt that the prevalent development framework’s drive towards economic growth is pushing towards the ecological collapse of the planet. In light of this dilemma, it becomes evident that wellbeing based on material growth tends to create more poverty for many, rather than a good life for all. Instead of proposing new “sustainable” or green-washed development frameworks, it seems necessary to propose new alternatives to the concept of development itself.

This entails, on the one hand, to essentially rethink the notions of wellbeing and quality of life, and, on the other hand, to reflect on the possibilities to translate alternative development ideas into concrete policies. There is an interesting approach along these lines, that seeks to measure wellbeing as a prerequisite to determining the levels of social development of any given country. Such approaches not only attempt to obtain concrete information about the quality of life of people, but also rely on the highly indicative value that these statistical indicators have both for politics and for individuals. These indicators are normally conceived as scientifically proven, neutral, rational and, as such, adequate to shape the patterns of life in the future, departing from current reference points.

For the purpose of establishing new and alternative definitions of wellbeing, new proposals have been adopted -especially those proposed by the Stiglitz Commission[1]– that bring interesting suggestions, without abandoning the mantra of economic growth. Precisely this is the goal of the index ‘Índice de vida saludable y bien vivida’ (IVSBV) developed by Ecuador[2]. This index merges the concepts of Aristotelian philosophy with the notion of Buen vivir – which is based on indigenous cosmovisions and has become widely popular in many Latin American countries and even a raison d’Etat and a constitutional right – and introduces ‘time’ as a central unit of measurement to determine quality of life. In this manner, Latin America continues to offer new and essential insights for development theory and research on wellbeing. The following sections present a historical account of the evolution of the concept of wellbeing, as well as the meaning of its measurement. A discussion follows on the introduction of the category of time as unit to measure wellbeing, and an examination of the methodological criteria underpinning the IVSBV-index, as well as its implications for addressing contemporary crises.

Towards an alternative to development, with the power of numbers

The idea of a national accounting system whose focus shifted from income to production emerged in the United States towards the end of the Second World War. While originally intended to facilitate efficient planning to sustain the war effort, the conceptualisation of this indicator fixated, at the same time, the basis of the current growth paradigm: with the establishment of the GDP as an indicator, economic growth became a valid parameter to measure development and wellbeing all over the world without an in-depth discussion.

Since then, wellbeing has fundamentally become associated to the production of goods and services. This has given the discipline of economics the power to define what is to be understood as development and wellbeing. The formula used is simple: through an allocation of resources considered as optimal, the market generates a large output of goods that increases material wealth. Individuals satisfy their consumption needs thanks to this varied supply, hence a higher production of goods means increased wellbeing for the individual. Economic growth thus expands the level of individual freedom, the subjective notion of happiness and everyone’s objective wellbeing.[3]

A central indicator is money, or else its purchasing power in real terms. In this way, the parameters used to provide an empirical measurement of wellbeing are usually income level, domestic product, or propensity to consumption. Thanks to its highly operational character, this approach has been welcomed by statisticians. The opposite to wellbeing is thus poverty, that is, the scarcity of material resources, which reduces the level of freedom and, in extreme cases, precludes the satisfaction of basic needs (such as eating).

Needless to say, there have always been criticisms to this approach. Soon, it became possible to demonstrate empirically that this supposedly transparent relationship between income and wellbeing was weaker than had been presumed, and that, above a certain income level, material growth was no longer associated to an analogous increase in wellbeing.[4] Until today, an important alternative to measure development continues to be the Human Development Index (HDI) of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), based in the Capability Approach.[5] This approach seeks to probe the social capabilities existing in each individual to achieve the highest possible degree of active freedom. The freedoms that can be measured and promote improved capabilities are democracy, institutions that compensate market effects, equality of social opportunities, transparency guarantees and social protection. In this approach, both objective and subjective aspects of wellbeing are taken into consideration, with a clear responsibility for development being assigned both to the contextual conditions (economics, politics, and the state) and to the individual (who must take advantage of the opportunities offered). This approach has significantly influenced many other efforts directed to determine alternative concepts and forms for the measurement of development up to the present day, including the important and already mentioned Stiglitz Commission.

Despite these initiatives, the level of development and wellbeing of the different countries in the world continues to be primarily classified in terms of their GDP. The influence of the ‘world’s most powerful number’ [6] and the underlying growth paradigm are still intact, ratifying also the normative power of statistical indicators over politics and society.

The social inefficiency of the alternative approaches mentioned is also found in the fact that – beyond the multiple initiatives otherwise – they continue to adopt Eurocentric notions of development. On the one hand, they cling onto the liberal conception of the individual, centred primarily on the idea of a rational subject and her individual freedom. The influence of the liberal theory of justice can be seen here, in its call for the expansion of equal opportunities for all under the motto of ‘equality through freedom’. In other words, each individual continues to be the seen as blacksmith forging their own destiny, but they have the right to be provided with a hammer and an anvil. Interpersonal relationships, collectives, social or ethnic groups are not taken into account, nor are matters of identity. Furthermore, these approaches continue to blithely prioritise material growth and an inherent promotion of capitalism as a central goal of development, while other dimensions (such as the environment or international inequalities) are relegated to a secondary consideration. In order to create an alternative to the mainstream notions of development and wellbeing that are also measurable and take the global socio-ecological crisis into consideration without compromising in efficacy, a more context-sensitive approach is required. It must rid itself of the liberal conception of the individual and of economicism, without renouncing to the ability for precise operationalisation. This is precisely what the IVSBV is aimed at.

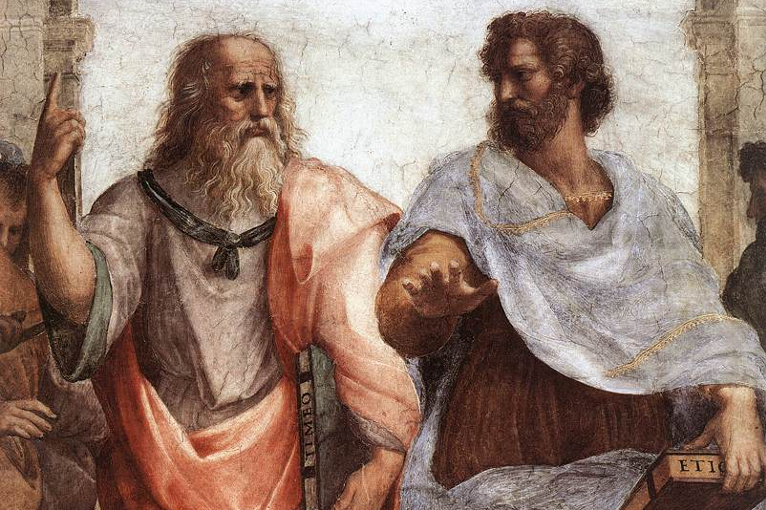

From a theoretical point of view, this index is based on the Aristotelian approach to the good life as successful action, eudaimonia. According to Aristotles, individuals can achieve a good life once they have achieved their material basic needs, enjoy good health and can devote their free time to leisure, reflection and introspection, interpersonal relationships, love, erotism, and to participation in public life. Instead of pursuing an ever better life (that is, to have more), what is sought is a good life in itself. Eudaimonia is thus not achieved through concrete goods or goals, but is rather a form of social praxis. In addition, the IVSBV also takes root in the indigenous cosmovision of buen vivir, which gives a great deal of importance to the relationship between the individual and the collective, and further advocates for a more balanced connection between human beings and nature. In this way, it seeks to satisfy all material, social and spiritual needs of the different members of a community without hampering other people or depleting natural resources.[7]

With this synthesis, the IVSBV takes clear distance from that which constitutes the basis of the mainstream notion of development and wellbeing: the liberal conception of individual and utilitarianism is challenged through a redefined notion of the subject as a social being embedded in an eco- environmental context. Wellbeing, personal relationships, and a healthy environment are thus inextricably linked together. Only a person who lives well – and within a community- can be happy and enjoy wellbeing. Precisely because of this, the constant increase of material goods also ceases to be regarded as a main factor to measure wellbeing, which implies a rejection of the growth paradigm. Therefore, the variables used by the IVSBV to measure wellbeing do not define individual happiness through static criteria (for example, material or other kind of quantitative measures). They seek instead to reflect the character of their sources: it is a matter of exploring the areas where wellbeing is generated, not one of measuring an accomplished goal. In that sense, the IVSBV dares to distinguish itself from Eurocentric approaches and avoids establishing universal goals for development or to propose fixed paths towards personal wellbeing, as these are defined (or should be defined) through individuals in each society.

Even while the importance of external living conditions is expressly highlighted, from this perspective, efforts to achieve material and health security come in tandem with other areas which have been found to generate wellbeing: time devoted to a) self-determined work, b) leisure and education, c) interpersonal relationships (love, friendship), and d) participation in public life. For the IVSBV, the (re)production of these areas represents an autonomous good, in each case. Contrary to what happens with market allocation, these goods are based on mutual recognition and social support. They are vital for human beings, but they can only be enjoyed collectively. They rely on recognition and intrinsic motivation, so that identity, communication, feelings, and empathy become important components. Hence, it is mainly about genuine personal relations, such as friendship and cooperation, erotism, family, civic commitment, or public participation. Since these goods are inherently reciprocal, they are denominated relational goods.[8] In this way, the IVSBV demarcates precise areas in which wellbeing is generated and within which it becomes measurable. The notion of the Good Life becomes thus operational[9]. In place of money, time appears now as a central indicator of wellbeing. The question is no longer how we want to live, but rather how we want to spend our time.

It’s time to develop a new measurement based on time

An approximation to the category of time begets the analysis of a complex phenomenon, that has been hitherto underestimated by the social sciences. In the first place, it seems important to recognise that time is not a physical or naturalised magnitude, as many in the natural sciences or philosophy still argue. In his essay on the topic, Norbert Elias insisted that our conception on these issues is based on a false dichotomy between nature and culture, which prevents us from acknowledging the social nature of time[10]. From a decolonial perspective, Walter Mignolo arrives to the same conclusion, and points out that since the eighteenth century, two main distinctions of Western modernity have been established as a duality: on the one hand, that of tradition and modernity; and, on the other, that of nature and culture.[11] Rather, time is a social institution created over a period of four millennia by humankind. Our current time regimes have emerged historically alongside processes of state formation in different societies. The introduction of new methods to measure time helped to coordinate and optimise political and economic action, while simultaneously rationalising and disciplining human coexistence. There is no doubt that the newest and more precise measurement of time was also an important contribution to the birth of capitalism: in the work sphere, it promoted the generalisation of waged labour, separated the working time from private life, and contributed to the differentiation of societies.

However, time has now such a deceptive effect that we are used to perceive it as something external. Conceived in the past as an instrument to harmonize coexistence, it now seems to have become for many (for example, as a result of its apparent shortage or acceleration) the autonomous baton of personal development. The category of time and the pressure-exerting effect of its social institutionalization have become a pattern of self-coercion that encompasses life in its entirety.[12]

In reality, however, time is a category created by human beings and, as such, remains a malleable one. If we consider that its availability has an evident influence on the personal and social state of being, measurable time appears as an ideal factor to redefine wellbeing and development. At the same time, given its relevance for any daily practice, proposals directed to modify the time regime have an orienting effect, both on the individual and in politics.

The idea to incorporate time as a component of economic theories and wellbeing measurement is nothing new. In general, Benjamin Franklin’s life motto ‘time is money’ occupies a central position. Time is thought of as a factor of opportunity cost, in a context in which the individual decides to use it either to earn money or to engage in non-productive activities, in which case they resign the opportunity of material growth. In this sense, free time continues to be a dependent variable in the economic sphere. It is only possible to ‘buy time’ if productivity increases or if we renounce to the material dimension. It is worth mentioning here Robert Goodin, who tries to integrate this magnitude into the calculation of wellbeing by using the concept of discretionary time.[13] However, this approach is also based on a liberal notion of the subject, and primarily rests on other economic indicators for its operationalisation. The same can be said of other recent and innovative approaches, emerging from Latin America.[14]

In the IVSBV, in turn, time is introduced as an independent variable. Through relational goods, the index defines precise areas for measuring wellbeing. It is the amount of time required to ensure the satisfaction of basic and material needs (rest, work, health), as well as the collective generation and enjoyment of the already mentioned categories: self-determined work, leisure and education, social relations, and participation in public life. This way, the point of departure for the IVSBV consists in incorporating these goods as variables, and to assign to social relations an important role in the measurement of wellbeing. Money stops being the main indicator of wellbeing and the main axis for its assessment, adopting instead the question of time available for social (and ecological) matters as a unit of valuation and analysis.

Despite the impossibility of offering a detailed methodological description of the IVSBV here, such description is easily accessible. In general lines, however, it’s worth highlighting that the characteristics of the IVSBV-logarithm, provide mathematical representation of the capacity of individuals and groups to generate relational goods through the measurement of the time therefore required.

In addition, the IVSBV is noteworthy for several other innovations. Given that work is no longer measured solely as a function of its capacity to ensure subsistence, but also for its quality as a source of autonomous wellbeing, new options emerge for regulating labor and for designing new strategies aimed at a more just organization of employment opportunities amongst people. The possibility emerges for assessing jobs and its associated social positioning through the capacity for self-determination of working time (rather than exclusively on the basis of income), as well as for a social revalorizing of activities characterized by high autonomy in terms of time.

On the other hand, with the IVSBV, re-productive activities (generally non-remunerated and performed by women) acquire empirical visibility. This includes, for example, domestic and care work, which are usually relegated in analyses despite the fact that they are crucial for sustaining or rising wellbeing. The IVSBV explicitly acknowledges that gender relations constitutively underpin productive relations. In order to revalorize hitherto undervalued reproductive services, the best approach would probably be keeping a systematic record of the time-slots allocated to caring and preserving human life, in par with other relational goods.[15]

With available national data as well as self-made household surveys, this measurement of welfare was put to a practical test in Ecuador, and compared to conventional methods. Polls confirmed the viability of the new procedure and yielded interesting results. The comparison of measurements operating on the basis of time versus those basing on income show substantial differences. Income no longer has a determinant impact on personal wellbeing: within the Ecuadorean population, the average income of the time-wealthiest 10% is three times lower than the top 10% earners. What happens is that higher income often correlates with longer working hours spent on a job characterized by a lack of autonomy, which constrains the ability to generate relational goods.

It goes without saying that this is not aimed at ratifying the slogan “poor but happy” and creating a dissociation between wellbeing and material status. On the contrary, the evaluation repeatedly emphasizes that an adequate material basis (income) is a prerequisite for achieving wellbeing; where such a basis does not exist, the level of wellbeing drastically drops by the lack of possibilities to ensure subsistence. The findings do however weaken the strength of the usually assumed correlation between income and wellbeing. On top of this, they reveal reasons for concern in the wealthy strata of the Ecuadorean socioeconomic hierarchy: out of the top 20% earners, only one sixth belongs to the group that has achieved maximum wellbeing in terms of time.

On average, according to the IVSBV, the country’s population only enjoys 11 years of wellbeing, which represents about a 14% of their total lifetime. There are great disparities here: the time-wealthiest 10% enjoys 16 times more weekly time for the good life than the bottom 10%. The greatest gap pertains participation in public life: the former decile’s participation is 35 times that of the latter’s, which constitutes a noteworthy finding not only for the theory of democracy.

Two factors substantially limit the rise in wellbeing: First, precarious working conditions. A sizeable portion of the economically active population – especially in the informal economy – perform low-skilled, high workload tasks, which can hardly even guarantee subsistence, let alone generating relational goods. A second factor – and tightly linked to the first- are the diverse forms of exclusion and discrimination (also on immaterial grounds, linked to geographic, ethnic, gender markers, among others) which exacerbate existing social inequalities and hinder the generation of relational goods. Among the Ecuadorean population, the time-poorest decile has only 4% of total lifetime available for the generation of relational goods.

This surely also explains why the IVSBV is largely unknown in Latin-America: where life and working conditions are precarious or even threaten the subsistence of large portions of the population, it would seem misplaced to advocate for more leisure time. In addition, and despite the fact that internationally the vision of buen vivir underpinning the IVSBV generates empathic reactions, ample adhesion and becomes a reference point for alternative political proposals, in its region of origin it has come under strong pressure. Even in Ecuador, the concept of buen vivir has long been politically instrumentalized, and was turned largely on its head, so that nowadays it tends to serve the legitimization of an idea of development that puts economic growth before the environment and justifies the extreme exploitation of natural resources.[16]

This conceptual emptying, however, and the derived concrete contradictions certainly do not invalidate the IVSBV as such, but rather confirm its key argument, namely: the way of measuring wellbeing implicit in the index presupposes a material basis capable of satisfying basic needs. If one takes into account, in addition, that the active population belonging to the middle strata has almost tripled worldwide between 1991 and 2015[17], the resonance for proposals aimed at a good life should be considerable, both within and outside Latin-America. Time can become a “second currency”, internationally recognized as an apt dimension for measuring wellbeing.

For whom the bell tolls: outlining a new politics of time

The IVSB has concrete programmatic implications: an “active politics of time”. It’s about a politics that, in a public and participatory fashion, seeks to have greater incidence in the time structures of people; and which clearly needs to affirm the concept of time as a social construction. It is essential that such politics does not rely solely on institutional and discursive structures, but focuses on real-world practices and sees that instruments are deployed towards a new time regime with positive resonance in the cultural sphere and in daily practices, which are adopted by individuals who take real ownership of them, and are oriented towards action. The politics of time needs to be implemented simultaneously in two imbricated fields. On the one hand, through institutional frameworks (such as state programs); on the other, through the social opening of new spaces oriented towards the real world, centred on self-determination in terms of time, and on the relationship between humans and nature. A politics of time shaped with these characteristics can create the cultural values without which it appears impossible to establish a new development paradigm that goes beyond economic growth.

On the basis of the Ecuadorian case, which reveals how informal employment and social inequality impose important constraints in terms of time prosperity, it becomes essential to promote dignified working conditions. In Latin-America this amounts, above all, to reducing the high level of informality, which not only hinders personal wellbeing, but remains the main obstacle to increasing productivity, and thus blocks any possibility of a type of economic development which goes beyond the polluting exploitation of raw materials.[18] A central goal of the politics of time thus consists in halving the regional rate of informal employment within the next 10 years.

In order to achieve this, a revalorization of care activities is unavoidable. If care services continue to be provided privately by individuals, many people will continue to resort to the family sphere and to cheap housekeeping work. The politics of time requires expanding public infrastructure (improving infant care, as well as that for people of age) and providing sociopolitical backing to reproductive activities (strengthening the moral and material recognition of care provision). In the same way in which the IVSBV shows that greater material prosperity often correlates to lesser availability of time due to increased working hours, high income earners living in Latin America with high levels of social protection should know that a reduction in working time can lead to a greater quality of life and to an economy which is more sparing of natural resources[19].

Beyond the two policy measures mentioned, the IVSBV identifies numerous areas for the application of an active politics of time. Even though it is not possible to provide a detailed account here, suffice it to say that they would be directed, for example, towards fomenting social relationality (with gender, family, and youth policies), promoting a high-quality education (through educational and cultural policies), and strengthening engagement in public life through diverse forms of participation.

It seems only logical that this new conception of wellbeing hasn’t had wider impact yet. The prevailing time-related regimes are linked to extremely complex structures, whose change can destabilize powerful institutions. However, more people than ever understand that it is not about struggling to improve one’s own life and that of one’s beloved ones, but, above anything else, to ensure the survival of humanity (and, with it, the future of their own children). Environmental issues have ceased to be the expression of an enlightened goodwill to become realpolitik. The IVSBV is thus a “timely” indicator. It orients development ideals toward non-material goals (therefore inherently sparing natural resources) without ignoring the importance of satisfying economic needs to achieve wellbeing. This model does not undermine the right of the dispossessed of this world to improve their material living conditions, but offers instead those well-off the opportunity of improving their own quality of life without an excess consumption of resources which hinders the possibilities of other people to improve their own (and in the last instance affecting also their own possibilities).This way, instead of adopting a moralising position promises increased wellbeing for all, facilitating its insertion and application in the field of politics and in the real world. For most of us, the idea of devoting more time to family, children, friends, leisure, public participation and outdoor activities in nature has hitherto had a very private character, which is not relevant to political claims. It is necessary for us to change this worldview so that the bells can toll for a good life.

NOTE:

This article was originally published in Spanish in Nueva Sociedad, in January 2018. It has been translated with authorisation from the Author and the Editors at Nueva Sociedad, to whom Alternautas is very grateful. The original article can be accessed here: http://nuso.org/articulo/bienestar-del-tiempo-respuesta-latinoamericana-frente-la-crisis-socioecologica/

ENDNOTES

[1] Joseph Stiglitz, Amartya Sen y Jean-Paul Fitoussi: Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress, 2009.

[2] René Ramírez Gallegos: La vida (buena) como riqueza de los pueblos. Hacia una socioecología política del tiempo, El Viejo Topo, Barcelona, 2012. – Translator’s note: This index’s name could easily be translated as ‘Healthy and Good life Index’. However, as the notion of “Buen Vivir’, from which it originates, the exact translation is a contested issue, as it references an indigenous notion that has been, in turn, translated into Spanish.

[3] This notion of wellbeing was made popular at the beginning of the European Enlightenment by the utilitarian ethics of Jeremy Bentham. With his greatest-happiness-principle (which postulates that the only goal of a rational behaviour is to achieve the maximum level of happiness to the maximum number of people), Bentham justified an almost mechanical conception of individual happiness, measured entirely in quantitative terms oriented towards material goods, without a space for qualitative considerations. See Martha C. Nussbaum: «Who is the Happy Warrior? Philosophy, Happiness Research, and Public Policy» en International Review of Economics vol. 59 No 4, 2012.

[4] Richard Easterlin: «Does Economic Growth Improve the Human Lot? Some Empirical Evidence» en Paul A. David y Melvin W. Reder (eds.): Nation and Households in Economic Growth: Essays in Honor of Moses Abramowitz, Academic Press, Nueva York, 1974.

[5] A. Sen: Resources, Values and Development, Harvard University Press, Oxford, 1984; M.C. Nussbaum: Woman and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000.

[6] Lorenzo Fioramonti: Gross Domestic Problem: The Politics Behind the World’s Most Powerful Number, Zotero, Londres-Nueva York, 2013.

[7] See, for example, Antonio Luis Hidalgo Capitán, Alejandro Guillén García y Nancy Rosario Déleg Guazha (eds.): Sumak kawsay yuyai. Antología del pensamiento indigenista ecuatoriano sobre sumak kawsay, fiucuhu / cim / pydlos, Huelva-Cuenca, 2014.

[8] The definition of these four ‘relational goods’ reflects a wide contemporary consensus of which are the dimensions considered important for a good life. The notion of ‘relational goods’ was developed and presented almost at the same time in 1986 by the philosopher Martha Nussbaum and the sociologist Pierpaulo Donati and used in 1987 and 1989 by the economists Benedetto Gui and Carole Uhlaner, respectively. See, Luigino Bruni: Reciprocity, Altruism and the Civil Society: In Praise of Heterogeneity, Routledge, Londres-Nueva York, 2008.

[9] This is not an attempt to advocate for empiricism, but to take advantage of the normative strength of empirical results to give quantitative measurements a bridging function, useful to transform concepts of development. This is a position adopted deliberately, considering that the development of categories and the selection of indicators are as structured in this index as they are in an economicist measurement of wellbeing, and that the indicators used by the IVSBV (such as years of schooling, the Gini coefficient, etc.) can only represent the existing reality in a limited or even distorted manner.

[10] N. Elias: Sobre el tiempo, FCE, Ciudad de México, 2010.

[11] W.D. Mignolo: The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options, Duke University Press, Durham-Londres, 2011.

[12] Hartmut Rosa: Alienation and Acceleration: Towards a Critical Theory of Late-Modern Temporality, NSU Press, Malmö-Aarhus, 2010.

[13] R.E. Goodin, James Mahmud Rice, Antti Parpo y Lina Eriksson: Discretionary Time: A New Measure of Freedom, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2008.

[14] Evelyn Benvin, Elizabeth Rivera y Varinia Tromben: «Propuesta de un in- dicador de bienestar multidimensional de uso del tiempo y condiciones de vida a Colombia, el Ecuador, México y el Uruguay» en Revista de la Cepal, 2016.

[15] For years now, a National Survey on the Use of Time has been implemented in 11 Latin-American countries, which provides a statistical measure of the total workload, accounting for both paid and unpaid work. According to the results obtained, women devote much more time than men to work, despite the fact that they more often appear as “inactive in the labor market” in records. V. Cepalstat: Encuesta Nacional sobre Uso del Tiempo 2009-2013; Cepal: Panorama social de América Latina 2014, Cepal, Santiago de Chile, 2014.

[16] H.-J. Burchardt, Rafael Domínguez, Carlos Larrea y Stefan Peters (eds.): Nothing lasts forever. Neo-extractivism after the boom of raw materials, UASB / ICDD, Quito, 2016.

[17] ILO: The transition from the informal economy to the formal economy. International Labor Conference. 104th Session, 2015, ILO, Ginebra, 2015.

[18] “Labor productivity, as measured by the GDP/working hour ratio, has been dropping during the past decade in Latin America, in relation to other more developed economies. On average, in 2016 Latin America represented one third of the labor productivity of the United States, a proportion that is lower as compared to that registered 60 years ago. This situation contrasts strikingly with the performance of high-growth Asian countries, such as Korea and more recently China, or even against commodity exporters such as Australia, where relative productivity has remained stable.” OECD, ECLAC and CAF: Economic Perspectives of Latin America 2017. Youth, Competencies and Entrepreneurship, OECD Publishing, Paris, 2016.

[19] The positive correlation existing between longer working hours and the more intensive use of resources /energy has been known for years. Tim Jackson and Peter Victor calculated a low / zero growth model, in which the working time could be reduced by 15% by 2035, without this implying a significant material loss. See: V. Anders Hayden and John M. Shandra: “Hours of Work and the Ecological Footprint of Nations: An Exploratory Analysis” in Local Environment, vol. 14 No. 6, 2009; T. Jackson and P. Victor: “Productivity and Work in the ‘Green Economy’: Some Theoretical Reflections and Empirical Tests” in Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, vol. 1 No. 1, 2011.

REFERENCES

- V. Anders Hayden and John M. Shandra: “Hours of Work and the Ecological Footprint of Nations: An Exploratory Analysis” in Local Environment, vol. 14 No. 6, 2009

- Evelyn Benvin, Elizabeth Rivera y Varinia Tromben: «Propuesta de un indicador de bienestar multidimensional de uso del tiempo y condiciones de vida a Colombia, el Ecuador, México y el Uruguay» en Revista de la Cepal, 2016.

- Luigino Bruni: Reciprocity, Altruism and the Civil Society: In Praise of Heterogeneity, Routledge, Londres-Nueva York, 2008.

- H.-J. Burchardt, Rafael Domínguez, Carlos Larrea y Stefan Peters (eds.): Nothing lasts forever. Neo-extractivism after the boom of raw materials, UASB / ICDD, Quito, 2016.

- Antonio Luis Hidalgo Capitán, Alejandro Guillén García y Nancy Rosario Déleg Guazha (eds.): Sumak kawsay yuyai. Antología del pensamiento indigenista ecuatoriano sobre sumak kawsay, fiucuhu / cim / pydlos, Huelva-Cuenca, 2014.

- Cepalstat: Encuesta Nacional sobre Uso del Tiempo 2009-2013; Cepal: Panorama social de América Latina 2014, Cepal, Santiago de Chile, 2014.

- Richard Easterlin: «Does Economic Growth Improve the Human Lot? Some Empirical Evidence» in Paul A. David y Melvin W. Reder (eds.): Nation and Households in Economic Growth: Essays in Honor of Moses Abramowitz, Academic Press, Nueva York, 1974.

- Norberto Elias: Sobre el tiempo, FCE, Ciudad de México, 2010.

- Lorenzo Fioramonti: Gross Domestic Problem: The Politics Behind the World’s Most Powerful Number, Zotero, Londres-Nueva York, 2013.

- René Ramírez Gallegos: La vida (buena) como riqueza de los pueblos. Hacia una socioecología política del tiempo, El Viejo Topo, Barcelona, 2012.

- R.E. Goodin, James Mahmud Rice, Antti Parpo y Lina Eriksson: Discretionary Time: A New Measure of Freedom, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2008.

- ILO: The transition from the informal economy to the formal economy. International Labor Conference. 104th Session, 2015, ILO, Ginebra, 2015.

- T. Jackson and P. Victor: “Productivity and Work in the ‘Green Economy’: Some Theoretical Reflections and Empirical Tests” in Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, vol. 1 No. 1, 2011.

- Walter D. Mignolo: The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options, Duke University Press, Durham-Londres, 2011.

- Martha C. Nussbaum: Woman and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000.

- Martha C. Nussbaum: «Who is the Happy Warrior? Philosophy, Happiness Research, and Public Policy» en International Review of Economics vol. 59 No 4, 2012.

- OECD, ECLAC and CAF: Economic Perspectives of Latin America 2017. Youth, Competencies and Entrepreneurship, OECD Publishing, Paris, 2016.

- Hartmut Rosa: Alienation and Acceleration: Towards a Critical Theory of Late-Modern Temporality, NSU Press, Malmö-Aarhus, 2010.

- Amartya Sen: Resources, Values and Development, Harvard University Press, Oxford, 1984.

- Joseph Stiglitz, Amartya Sen y Jean-Paul Fitoussi: Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress, 2009.