Ed. note: This is a substantial rewrite of a former post of Wayne’s from early 2017: How Does Your Local Food Grow?

CAN WE BUILD A LOCAL FOOD WEB TO DISPLACE THE GLOBAL FOOD CHAIN?

There was a time in the not-too-distant past when local food was about the only food on offer. Then came a time when long-distance food had everything going for it, including major technologies (railways and iron ships, for example), huge corporations, and massive government subsidies.

In today’s world, we can choose what I’ll call the neo-local choice. For the first time in history, it really is a choice. It’s not imposed by old technologies that offered no alternatives but the food at hand.

We have the opportunity and capacity to choose neo-local food in an era when modern technologies and inventiveness provide year-round local options that are varied, fresh, affordable, authentic, and delicious, as well as environmentally responsible.

It’s not your grandmothers’ local food. This time, we have both logic and logistics on our side.

A few years ago, I went to and wrote about an exciting international conference in Montpelier, France, on sustainable “agri-chains” — which is geekspeak for food supply chains.

I’ve now learned enough to propose that community webs need to displace agribusiness chains. These chains are locked into dysfunctional, one-way, linear, profit-obsessed ways of mishandling food. They damage the health and well-being of economies, environments, and communities.

The whole idea of long-distance food systems is farfetched.

Eaters of the world, unite! You have nothing to lose but your food chains!!

First, let me outline how we got to where we are now, so we know what we have to climb out of.

HOW WE LOST COMMUNITY-BASED FOOD INFRASTRUCTURE

Nature abhors a vacuum, and something always rushes in to fill it. It’s the same with economies.

There was a food infrastructure vacuum in many European cities of the 1800s and 1900s. Almost all the new investment rushed into investments in infrastructure for imports and exports. Refrigerator ships, trains, trucks, docks for ships, stations for trains, superhighways for trucks, mall parking lots for cars and gigantic processing and warehouse facilities were installed to move food across vast distances.

In the absence of community-based or government-funded mechanisms to support a robust local economy, national and multinational corporations came to dominate the profitable intersection connecting consumers to food. Under-capitalized main streets and farmers markets — as much part of the public commons as part of the marketplace — couldn’t keep up.

There’s a vivid presentation of how this went down in the BBC documentary series called Full Steam Ahead. Trains transformed the food landscape between 1850 and 1914. They brought coal to every community on the train line. Coal-fired stoves soon replaced wood-fired fireplaces as the way food was cooked. The one-pot meal cooked over a wood fire was replaced by stovetop meals with three or more dishes.

Before the age of steam, cities were fed almost entirely by the countryside within a day’s walk or horse ride. Cattle and sheep were shepherded live to the city slaughterhouse. Horses and carts brought in highly-perishable milk or perishable produce.

That discipline of being able to feed itself from its own region limited the size of cities. It also made food production a visibly important aspect of city life. London, for example, the largest city in the world, was home to 25000 cows, producing milk that had to be drunk before it soured. (Before the railroad was also before the refrigerator.)

Equally important, the size and reach of pre-railway cities limited the scale of food businesses. For the most part, businesses only had to be large enough to serve far fewer than a million people. Except for non-perishable foods (chiefly baked goods with lots of sugar acting as a preservative), national food corporations made little sense.

Trains not only made Scotch whiskey and Devon cream available to a national market for the first time. They made national and even multinational corporations profitable. During the early 1800s, French emperor Napoleon insulted Britain by calling it a “nation of shopkeepers.” Indeed, high streets (main streets) were home to local butchers, bakers and candlestick makers.

Less than a century later, the nation of shopkeepers was on its way to becoming a nation of employees. Local food businesses were overshadowed by national processors, distributors and retail chains. They positioned themselves midway between farmer and eater, in the knowledge that money in the new food system would be made by “middlemen.”

These new boys on the business block had a vested interest in a long-distance food system. The transportation, warehousing and storage infrastructure of the new system was designed to meet the needs of national corporations, not local businesses or local customers. The further apart producers were from consumers, the more pivotal and profitable the connecting role of corporations.

Today’s pundits might call this transformation of the food business an early version of “disruption” — as if a superior socio-technical system simply displaced an obsolete one.

That’s not how it went down. Local businesses were defeated largely because government resources, from subsidies to infrastructure to laws, went to support national and multinational food corporations, not local ones rooted in a community.

It was not disruption that drove local food webs out of business. It was outgunning, made possible in large part by government favoritism — be it laws favoring the limited liability and social responsibility of corporations, laws overlooking predatory behavior by monopolies, failure to regulate food adulteration, failure to regulate environmental pollution (all of which are called regulatory subsidies) or outright cash subsidies to new corporate infrastructure. Local farmers and artisans lacked government support, which was where the battle was won.

Local food infrastructure for local food suppliers and artisans wasn’t just a low priority for the new food corporations. Local was the competition. National and global corporations won out during the railway and iron ship era (approximately 1850–1950), and again during the trucking and container ship era (approximately since 1950).

COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS

There were many food-related benefits to rapid long-distance transportation made possible by railways. Most notably, people were able to eat a much wider range of perishable foods than people had been able to access earlier. For the first time, for example, fish and chips became a national dish across Britain.

But from the perspective of the early 21st century, the railway era embedded several systemic ruts in a food system which have been maintained and deepened in the era of trucks and container ships.

The most farsighted analyst of the “creative destruction” imposed on food systems by railways proved to be none other than Karl Marx.

Marx was best known in his day for his views on the class struggle between workers and capitalists. But his sensitivity to the struggle between economies and natural environments was only fully appreciated long after his death, and long after Russian and Chinese Revolutions claiming inspiration from Marx (see here and here and here).

Marx situated his understanding of class struggles within a framework of relations between humans and Nature (Man and Nature, as it was known in his day). To put it indelicately, Marx was vexed by what would happen to city poop and countryside soil when the land where food was produced was so far from the places where food was eaten, digested and pooped out.

Marx understood that the Age of Steam disrupted the very metabolism and digestive system that had previously governed the scale and relations between people and essential natural processes of soil fertility and renewal. Once long-distance food became the norm, farm soil lost the humanure (called “night soil” in China) which recycled, renewed, and enriched the soil’s original nutrients.

That system of back-and-forth exchange was replaced by one where second-rate soil fertility was supplied by purchasing chemicals, while the superior human poop of the city was dumped as waste into rivers and oceans, lost to fertility forever. Soil came to be treated like dirt.

The food culture associated with the natural exchange of services between humans and nature was likewise transformed. Throughout most of history, the pursuit of food was a front-of-mind issue, and a highly visible one. Suddenly, to use an awkward academic phrase, food produced far away was taken for granted and all but “invisibilized.”

In a long-distance food system, peoples’ eyes are too near-sighted to make out how complex, connected, and fragile the whole world system is.

In short order, the countryside closest to expanding cities, usually the site of very fertile land, was gobbled up for suburban sprawl. Farms were located beyond the line of sight of city planners and public health officials.

As Carolyn Steel notes in her majestic study of Hungry Cities, the urban planning profession created to serve the new generation of metropolitan cities of the early 1900s was raised during the era when food ceased to be a preoccupation of city leaders. By and large, city planning ignored food’s physical and social role in nourishing the urban landscape throughout the 20th century.

The idea that food was a “whole of society, whole of government, whole of personhood” necessity almost vanished, until revived by food movements of a new century. Instead, food was seen through consumer’s eyes and measured by its cheapness, not by its many contributions to health and well-being, of both rural and urban populations. Almost all governments slot food in the agriculture department, not the community or health departments.

One function of the new food web emerging today is to overcome such blind eyes that became encrusted in the food logistics of post-railway cities.

MEANWHILE BACK IN THE COLONIES

The export orientation of modern agriculture was deeply embedded in North and South America, right from the beginning of European exploration and colonization. In a nutshell, European colonizers saw the Americas as places to pillage and exploit for luxury goods — above all silver, gold, furs, tobacco, and sugar.

As this article reveals, the earliest European colonial settlements, such as Virginia, turned to farm exports before 1620. They survived on foods provided by Indigenous peoples and farmed fundamentally useless goods for export. Slavery and piracy were essential to these export-led economies, the first indicators of a new world order that’s been called “the Capitalocene,” the force behind today’s “Anthropocene.”

The export-led economy of the Americas peaked during the period of England’s industrial heyday. That’s when expansion into the North American prairies was designed to provide cheap grains for the underpaid and under-nourished British working class. The design of North American farming, warehouse, and transportation systems was all about meeting exports to England. (This dominant drive behind North American and “settler state” agriculture and food development is explained in the “food regime” concept of Harriet Friedmann and Phil McMichael, explained here. The grave environmental and social impacts of this food regime are analyzed here.)

If you ever wonder why Canada and the United Stets were each competitively built as continent-wide countries stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific, look no further than this strategic economic imperative to deliver cheap grain from the Americas to Britain.

The “giant sucking sound” of the late-1800s was not what former US presidential candidate Ross Perot in 1992 likened to the sound of industrial jobs sucked away from North America to Mexico under the North American free trade deal. Back in the day, the sucking sound came from “grand trunk” railways in both countries vacuuming up Western grains and cattle to be exported to Britain.

One railway empire recognized its food exporting function in its very name. It was built as a trunk line, akin to an elephant’s trunk. It sucked up goods from somewhere far away to somewhere far away. It was not designed to serve the transportation needs of its host communities or their regional food systems.

Even today, logistics planners fret over what’s called the “last mile” — all the problems associated with getting deliveries that have come from 3000 miles away through the traffic jams and narrow streets of a busy city for their final destination. Local remains an afterthought for people who make their money moving goods.

I have my own front-row seat to look at this historic importance of food infrastructure. I live a short walk from Main Street in the Toronto Beaches, designed to be the main street of all North America — the plan being that the Grand Trunk would bring grain from the North America prairies through Toronto, through to ports in Montreal and Halifax that could ship food to England in both winter and summer. The railways kept these lands in the Beaches for almost a century, when they made their fortunes selling land for housing developments instead of railways.

The powerful momentum of global corporations triumphed over the stagnant air created by two forces that sucked the oxygen out of direct relations between nearby communities. One is called market failure, and the other is called collective action failure.

“Collective action failure” is the inability of some groups to mobilize people to correct a problem they have in common with others. The inability of farmers who need more local food sales to make common cause with local city people who would benefit from jobs processing local food is a classic case of collective action failure.

“Market failure” is the inability within business communities to discipline one another to solve a problem because one tiny group of businesses benefits from the problem not being solved. Many local government programs began because of market failure. Leaving sidewalks to the private sector doesn’t work because there’s no value to having competing sidewalks on a street. The same goes for firefighting.

To give a less obvious example, many cities provide relatively low-cost parking in downtown areas because the business class on its own can’t get it together to set up a parking lot to compete with an overpriced parking lot that is turning away customers all the businesses in the area need. Local business failures to support each other in business-to-business food purchases is a classic case of market failure. The inability of restaurants to agree to limit “American plate” portion sizes that cause obesity and food waste is another example of market failure that needs government regulation to correct it.

The absence of local food webs is the result of both these failures — the inability (to date) of city and countryside residents to collaborate on local food purchasing that would benefit both groups(collective action failure), and the inability of local small businesses to cooperate in building a local food hub that would serve them better than centralized private corporate distributors (market failure).

Humans are social animals, but we have problems with alpha males and lone wolves that have kept us — until very recently — from being our best selves.

WHY LOCAL FOOD WEBS ARE IN THE WORKS

Today, by contrast, community groups, civil society organizations, and local governments can access the technology, knowledge, policies, and communication systems to launch and embed the necessary infrastructure for local food connections. We have a greenfield opportunity to go back to the drawing board and design a web-based metropolitan food system.

Henk Renting, one of the forecasters of emerging “short” (rather than long-distance) food systems

I want to propose some projects to policy entrepreneurs and business entrepreneurs willing to come together at a drawing board. My ideas, which came together for me at the Montpelier conference, draw on the thinking of Tom Lyson’s prophetic book, Civic Agriculture, and Henk Renting’s game-changing article on Civic Food Networks.

I mainly want to flesh out how such new food webs might be started.

The dominant food supermarket retailers, as innovative as their technology was 75 years ago, is a product of the old bricks and mortar economy that’s now being disrupted by software-enabled warehouses that do door-to-door delivery and bypass the cost of a local retail presence in local malls or on local main streets.

But two can play the software game, and the alternative, community-based economy can use software to enable close relationships among people who share common neighborly interests.

It’s time for the food movement to catch up with the rest of the economy, and take better advantage of the urban advantage, new social technologies, and new networking abilities.

The best-known urban advantages are explained by Jeb Brugman’s Welcome to the Urban Revolution. Cities bring together large populations, which ensures an opportunity to provide some scale to a diverse range of businesses. Cities also bring people close enough to bring “the costs of collaboration” almost down to zero. No need to travel to conferences for a meeting. No need for hugely expensive offices as the only way to provide face-to-face intimacy and brainstorming. People with a wide range of skills can launch a new operation after huddling around their laptops over a table at a neighborhood coffee shop.

These two urban advantages provide the edge that a predominately local food system thrives on. It makes a local system competitive with a global system in terms of its access to the exchange of ideas and products.

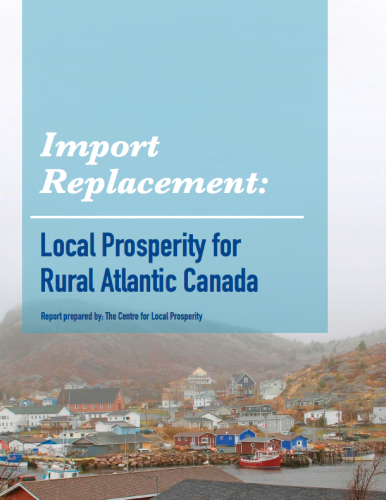

THE IMPORT REPLACEMENT FUNCTION OF CITIES

Behind that is the simplest urban advantage, explained to me by my friend Phil Groff, former head of Sustain Ontario: the Alliance for Better Food and Farming.

“From the very start,” Groff told me while driving me to a meeting a few hours away, “cities have been about import replacement.” Instead of one of the world’s first farmers buying tools from a peddler who wandered around the countryside selling tools, he or she went into town and checked out a tool shop that hired local tool makers. Instead of the toolmakers ordering food from peddlers who walked or rode animals thousands of miles from their home farm, shoppers bought their food at the local farmers market, just outside the city gates.

Stepping into the future: cosmopolitan cities with active citizen groups have all the makings to develop alternatives to imports brought in by supermarkets tethered to the long-distance chain of vertically-organized corporations. Co-ops are one option, according to Jon Steinman’s study of Nelson, B.C. (advance copy)

The reason why cities and agriculture co-evolved from the start — the marvelous theme developed by both Jane Jacobs and Carolyn Steel — is that they need each other as customers so people are free to go about their best work and enjoy each other’s company (a word that descends from Latin roots for with and bread) after work is done, and talk about ways of working smarter.

The industrial revolution upset that import replacement applecart, replacing it with impersonal trade that had little to do with proximity or logic or social interaction, but had mostly do with specialization — leaving us with cities where workers made certain metallic widgets for export to distant markets, while farmers in nearby countrysides grew food widgets for distant markets, and both lived and worked in parallel but separate universes.

The new food webs will bring sense back to food and other economic relationships, and revive the ancient function of city-countryside relationships growing from place-based import replacement.

Place-based import replacement makes huge sense in a world suffering from multiple ecological crises. That’s because local and place-based economies are made for circular economies that can reduce packaging waste by relying on reusable containers, and then recycle and “upcycle” other wastes into services and products — as when food scraps, mixed up with biochar from scraps of waste wood, are upgraded into high-value compost.

By contrast, the muscle-bound inflexibility of linear chains inevitably ends up externalizing waste far away, where it is expensive or impossible to deal with. To add to the expense and insult, the local government and population are left holding the bag for the cost of coping with these externalized problems.

Anything you can do, I can do fresher.

The food chain only travels from farm to fork, but a food web goes full-circle — from soil to post-consumer compost and humanure that enhance soil, after being carted back to the farm in a truck that used to return home empty. To deal with waste and externalities, we need to go from beginning to end of a full lifecycle, not just from beginning to end of a producer-consumer commodity chain.

In this era, the absence of circularity in stodgy old linear supply chains is a fatal flaw — disastrous for both the supply chain and the planet. That’s why moving to a place-based web is both essential and urgent.

THE FOOD BUCK STOPS HERE!

Here are some ways that the disruptive innovation known as the food movement can and already does enable direct connections that used to be controlled by corporate intermediaries, just as Air B & B disrupts global hotel chains.

I’ll only give two of many possible examples — one from the formal public sector, and one from civil society.

- UNIVERSITIES: Universities are very much in the avant-garde when it comes to organizing purchases from local and sustainable (as well as global and sustainable) producers.

Several universities — most notably the University of Toronto, with the largest student body (over 90,000) in North America, and Nottingham Trent University in England (analyzed here ) — already manage direct relations with food producers without any support from major global corporations.

Many of these universities feed populations larger than typical towns and small cities. University bulk orders are often large enough that the university can offer to receive deliveries from a hub, that can also service nearby retail and social service outlets.

(For a US university-based experience, see here. For the UK experience with Food for Life Catering Mark, see here.)

2. CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANIZATIONS: Community-based groups can host direct relationships between communities and nearby farmers or fisherfolk. That’s what happens with Montreal-based Equiterre, which sponsor Community Support Agriculture relations linking 100 farmers with over 15,000 families (40,000 people) across Quebec and New Brunswick.

In Italy, as reported in a book on food policy in Turin, community-based organizations such as Solidarity Purchasing Groups and Collective Purchasing Groups orchestrate direct relations linking farmers to over 2300 families.

Impressive numbers and impacts are doable.

3. THE UTILITY MODEL: Local public services and utilities, which often have a mandate to use their buying power in the public interest, can play a pivotal role in boosting the volumes of local food sold in an area. Some excellent articles have been written on successful efforts, available here, here and here. Such local and sustainable purchasing practices have already done wonders in terms of public utilities transforming the landscape for local and renewable energy producers. Why can’t this be matched when it comes to energy from local and sustainable food?

Brazil successfully applied this approach to public school purchasing, requiring that 30 percent of school meals come from small local farmers. Such requirements can be started by requiring a readily-achievable 10 percent local and sustainable purchase in the first year, gradually moving toward 30 percent and beyond, as local capacity builds. Such practices can be spread across the public sector.

Toronto-based Real Food for Real Kids provides a best-practices example of how local, sustainable, healthy, delicious and well-priced foods can be delivered to nursery and elementary schools in this way. The Los Angeles school board offers another leading-edge example.

promotion of a hub in Australia

4. HUBBA HUBBA: Hubs in a wheel gather and distribute the strength of many individual spokes. Hubs do the same for small individual producers and consumers in a regional food system. Producers may share common overhead costs such as warehousing and delivery. By aggregating their buying power or by sharing their overhead costs, they can achieve some of the advantages of an outsized competitor. Hubs area modern-day food example of the ancient principle: “all for one and one for all.”

There are 400 hubs in the US, where the USDA has supported them with grants and information. About 30 percent of these hubs are non-profits, according to report from leading nutritionist and food system analyst Fern Estrow. She provides this link to a critical study. (For a nice, brief summary of US hubs, see here.)

The Toronto Public Health Department, where I worked for many years, sponsored a buyers’ version of this hub function, which centralizes purchases for non-profits and food banks, allowing members to order high-quality local foods at a wholesale rate. This initiative now operates out of North York Harvest, an innovative food bank. I wrote about such local initiatives here and here.

5. CO-OP NATURALS: Many co-operatives grew up during the 1800s and early 1900s when small rural producers, be they farmers or fisherfolk, often lived in isolated regions that established companies didn’t serve at anything like an affordable fee.

Other co-ops arose to assert self-reliance, collective power, and positive identity among groups that were looked down upon by the likes of bankers. Credit unions were strong among early Canadian unionists.

Popular banks became a mighty force among French speakers in Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and even New England. Now called the Mouvement des Caisses Desjardins, Quebec-based credit unions control over $150 billion in member savings and exert their strength in the financial and overall Quebec community. In Vancouver, progressive individuals gain financial clout by supporting VanCity credit union, which has assets of over $20 billion. It was one of the first financial institutions to provide mortgages to workers and to recognize women in their own right. VanCity is also a generous supporter of several local food projects.

Since the 1970s, some producer and consumer groups in the food and farming sectors have opted for new generation co-ops or second-wave co-ops, as ways to buy, sell and add value to products, and also to express shared beliefs.

6. STAND ON, STAND FOR:

“What I stand for is where I stand on,” is Wendell Berry’s famous statement on standing your ground. Local governments can support and enable resident action to promote local food security and food sovereignty by affirming a resident’s right to grow food on front and back yards or to set up a food stand selling produce from that home garden.

The means to connect producers to consumers are now easily and cheaply available through an organization called Seed Voyage (linked here), which takes five cents on the dollar in return for matching up the perfect producer to the buyer who’s rarin’ to meet the producer of their longed-for food. It’s as simple as Internet dating for garden produce!

7. HOW LOW CAN YOU GO?

The European principle of “subsidiarity” holds that power should reside “as low as possible, as high as necessary.”

Many people are surprised to learn just how many projects can be well-managed by local people using local resources. Local capacity has been transformed by modern-day education, which has made higher education accessible to many, and by new information and communication technologies. Once-obscure and arcane information is now readily available to someone who can operate a laptop at a coffee shop.

Local imagination and sensitivity also come in handy. One of my favorite interventions by a local government comes from Hampstead in London, England. The local council purchased a few storefronts on main streets to ensure there would always be retail space for neighborhood food stores, so that food security would not suffer as a result of land speculators gouging local food outlets.

8. FOODS OF LOCALITY: Local governments can also download (upload???) decision-making authority to enable and empower neighborhood residents to directly choose certain kinds of food services.

Some neighborhoods give birth to neighborhood or county or city “namesake foods” that are endowed with hyper-local cultural terroir. Canadian food analyst Lenore Newman calls these “foods of locality” — not just any old foods that are grown locally, but foods that literally come from the cultural geography of a place.

This is the case of the Chicago hotdog, for example, which could pass “mustard” as being reasonably healthy and as having a meaningful history relevant to the culture of its birthplace. Needless to say, as much as possible of the namesake food would be grown, processed, and prepared in the locality.

Today’s local interest in food has created a revival of enthusiasm for “cottage industry” methods of food production. Virtually all state governments in the United States have developed special regulations for such establishments.

The common sense regulations take into account the fact that regulations for a corporate slaughterhouse behemoth are not appropriate for a church or at-home kitchen preparing dishes for 50 people — a typical crowd that might reasonably come over for a lightly-regulated party or celebration. As a variation on such cottage industry rules, Toronto regulates small and artisanal processors as if they were restaurants; restaurants have a high standard for safety, but not as painstakingly expensive and intrusive as they need to be for corporate-sized plants.

9. MAKING HISTORY: Civic museums and historical sites often have boards of directors recruited from the neighborhood. Imaginative directors influenced by today’s public interest in food can attract new visitors (tourists and schoolkids, for example) by hosting a farmers market, a gift store featuring foods prepared at the museum, and gardens featuring production methods during the time of the original building’s full glory.

One Toronto example of this is Montgomery’s Inn — now near the heart of the city, but in pioneer days of the 1840s a stagecoach stop for travelers going west and a haven for runaway slaves from the US. Today, the Inn sponsors a year-round farmers market and a baking oven where old-time bread is made.

Another example is Toronto’s Old Fort York. That’s where Toronto was defended from US invasion during the War of 1812. The fort features many food activities with a historical theme, serves vintage foods in its coffee shop, and has a garden identical to the fort’s original one. The site boasts a range of non-formal learning activities which virtually invite history teachers to hold a class trip.

10. EAT THE WHOLE THING:Food has been called a “whole of government” and “whole of society” enterprise. Virtually every department of a government and every unit of society has to engage with food at some point. Just as families and friends share meals, so governments and societies must share responsibilities. That’s why food ultimately belongs in the social economy and the sharing economy.

seeding the sharing economy

Under the whole-of-government canopy, libraries make a contribution by lending more than books. They can also loan the information stored in local heritage seeds. That’s what a seed library does. When libraries really get into the swing of things, they can also become leading members of the new “sharing economy” (explained to you, where else, in the best-known example of the sharing economy, Wikipedia) and lend kitchen equipment and set up tool libraries for garden and cooking tools.

11. NOT GOING THE EXTRA MILE: Entrepreneurs willing to invest in system-wide business relationships will play a decisive role in promoting a local and sustainable food system. Governments may steer the food boat toward a local and sustainable landmark, but roll-up-their-sleeves businesses and workers will do most of the rowing.

Food is fundamentally a logistics business, as I have argued in my book, The No-Nonsense Guide to World Food, and the logistics of a local and sustainable system will be challenging in the extreme. The food businesses of tomorrow will go where no businesses have gone before. They will create a whole new spin on doing more with less — less in the area of pesticides, miles traveled, and so on, and more health, equity, neighborliness, and sustainability.

Going the extra kilometer by not going the extra kilometer

In Toronto, the relationship orientation of such companies is prefigured by 100 Kilometer Foods, a valued part of the local food community, as shown here.

12. GOING GLOCAL: We don’t live in a world that is EITHER local OR global, my way or the highway.

We live in a world of both…and.

Eliminating or reducing totally unnecessary or redundant transportation — carrots being imported into New York State, even as carrots are exported from New York State — may cut as much as half the amount of food transportation involved in transporting food. Much of the rest of the burden of transportation can be substantially slashed by growing a wider range of non-traditional foods in each locality.

Having said that, few people are going to give up coffee, tea, and chocolate any time soon, and few will want to forsake tropical foods during the winter. However, that desire for global foods is an opportunity, as well as a problem. Many foods from afar aren’t perishable, so delivery doesn’t have to be rushed. many products might be transported in wind-powered ships and electric trains.

Another important thing to remember with many foods from afar — this is especially so with coffee and chocolate — is that they are perennial plants that are best grown in sustainable “forest gardens.” As such, they actually store more carbon in the soil than they burn in the course of efficient transportation.

Fairtrade towns have spread across Europe and North America

Cities are already a significant force in this wholesome trade. Especially in Europe, many have signed on as fair trade towns. If the city government isn’t ready yet, churches, university and college campuses and a wide variety of coffee shops are ready to step into the breach.

This listing of 12 options that are ready to go right now hopefully suggests that the opportunities to move the needle on a new food web are almost endless.

We don’t need gigantic global corporations to make the shift to a local and sustainable web. Indeed a 2019 report on the top ten global food companies reveals that few of them make more than “incremental” reforms (better labeling, for example). Even fewer are making “radical” or “transformative” changes in the direction of sustainable development goals. The big brands argue that tiny companies aren’t up to the scale of sustainability challenges, but this report shows that most of the changes the big brands take credit for come from maintaining previous practices of tiny companies they bought up.

That’s Harriet laughing, and she may be talking to me, when I had a bit of hair, and Debbie Field.

The old food chain was run by chains. The new food web will be a weave.

We do need what global food system scholar Harriet Friedmann calls a “community of food practice.” She’s referring to the overarching and cross-cutting community agencies, government departments, business roundtables, unions, food policy councils, and citizen groups that will weave the “collaborative infrastructure” of an emerging food system.

The famously successful co-ops of Mondragon, Spain had a slogan that “we build the road as we travel.” My own jest at the workstyle I maintained when I managed the Toronto Food Policy Council was “we build the airplane as we travel.” But the task at hand requires that we weave the web as we interweave. “We are what we do,” Sting might say if he ever does a food-oriented musical akin to The Last Ship. “We build webs.”

(If you like this kind of thinking, please check out my free newsletter on cities and food, at bit.ly/lettersfromwayne Thanks!)

Local food has a multiplier effect — in the economy and society — a virtuous circle displacing a vicious circle.