Last week Vox published an article on the global poverty debate. The piece – by journalist Dylan Matthews – raises a few issues that I think are worth addressing. I set out nine brief points here, responding to specific quotes from the article.

1. “As Roser is quick to note, it’s not ‘his’ chart — it’s similar to charts many economists working on poverty have produced, such as one in Georgetown professor Martin Ravallion’s book The Economics of Poverty.”

There is in fact a key difference between the two charts. It all comes down to context. Ravallion’s is in an academic text that is intended primarily for circulation among academics. The inadequate nature of the long-term poverty estimates is well known among academics, who take them with a big grain of salt. Roser’s chart, on the other hand, is an infographic designed for mass consumption on social media. The chart itself – as in the version Gates tweeted – makes no reference whatsoever to the problems with the data. On the contrary, it creates a powerful illusion of certainty. A key piece of my argument has been to say that this is irresponsible public communication. That’s why I say the chart should be taken down.

2. “Roser, as he stressed repeatedly in messages to me, just wants to be clear on what the facts say.”

If Roser wants to be clear on what the facts say, then he should refrain from making claims (i.e., about long-term poverty trends) that are not backed up by actual facts. The whole point of my argument is that the data he uses to draw conclusions about global poverty trends from 1820 is in fact not valid for that purpose.

3. On higher poverty lines: “Roser himself agrees, writing in a Twitter DM, “I also very much agree that higher poverty lines are important to use.”

Great! So if Roser agrees that higher poverty lines are important to use, then he should stop using the $1.90 line in his flagship graphs (i.e., the one Gates tweeted). The weight of evidence is clear that $1.90 is not adequate. If the World Bank itself states that it is too low to inform policy, then it’s also too low to inform public debate.

4. “It’s true that the proportion of people living on under $7.40 a day fell less rapidly than the proportion of people living on under $1.90 a day — but what that tells us, primarily, is that there was a large group of outrageously poor people subsisting on, say, 50 cents a day, who in recent decades have climbed up to earn, say, $2.50 per day. That’s not good enough by any stretch of the imagination, and they deserve more help. But that’s nonetheless real progress that a higher poverty line deliberately excludes.”

A few things about this.

First, a higher poverty line doesn’t “deliberately exclude” real progress. That’s a silly accusation. After all, the $7.40 line is not arbitrarily high. It is what researchers say people need in order to achieve basic nutrition and normal human life expectancy. The reason it is important is that it reveals that the small increases in income that Roser’s graph depicts as “progress against poverty” are in fact not adequate for lifting people out of actual poverty. We need to face up to this fact.

Second, my point is not only that using the $7.40 line shows that the proportion “fell less rapidly”, as if we’re quibbling about a tiny difference here. No, the argument is much stronger than that. The $1.90 line creates the impression that virtually nobody remains in poverty today (a mere 10%, perhaps), when in reality the increase in income among the world’s poor has been so meager that only a small proportion of people (almost all of them living in China) have actually escaped poverty, while a full 58% of the human population remains poor. As I stated earlier: that’s not progress – that’s a disgrace.

The question we have to face is this: is it legitimate to say that the global economy is working when 58% of the human population is in poverty? My answer is a firm no. Matthews and Roser evade this question.

Third, to say that incomes have increased from 50c to $2.50 is optimistic. In reality the average gain has been at most a doubling of income since 1980. That’s how slow it has been. And once again, while incomes have increased by very small amounts, they have not increased enough to raise people out of poverty. Not by a long shot. This is why the Gates narrative is so misleading. Here is a graph showing how much people’s incomes increased during the period 1988 to 2008. Take a look and tell me… “real progress” for whom?

Finally, it’s not that the poor deserve more “help”. What they deserve is a global economy that is fundamentally fairer – that’s the argument I lay out in The Divide. The poorest 58% render underpaid labour and cheap resources for mass consumption and elite accumulation, mostly in the North. It is offensive to suggest that what they need in return is charity. What they need is justice. Sadly, that’s something that the Gates narrative cannot abide.

5. “On absolute numbers, I fear Hickel has a weaker case… Using absolute numbers risks confusing reducing poverty with preventing poor people from existing.”

This is a very strange argument, and an exact inversion of reality. In fact it is those who object to the use of absolute numbers that trundle out this argument. They say we can’t use absolute numbers because the only reason the number of people in poverty has been rising is because the poor are living longer, and reproducing. This argument only makes sense if you start from the assumption that poverty is a natural condition – as though being born into poverty is a kind of default. My position is quite the opposite: that poverty is not natural at all, but rather an artifact of policy, and that in a world as rich as ours poverty needn’t and shouldn’t exist. So any additional person in poverty is an injustice – a product of an economic system that has been designed to direct our planet’s abundance disproportionately to the already rich.

Matthews eventually gets around to acknowledging this point, but only after first distorting my position.

Also, he has said nothing about my initial reason for insisting on absolute numbers, namely, that this is the metric that was first adopted by the world’s governments in the Rome Declaration in 1996. The switch to proportions was made in 2000, apparently – according to research by Thomas Pogge I cited earlier – because it made the goal of “halving poverty” easier to achieve.

Matthews says: “What most people in the development field want to ensure is that the people who do exist, however many of them there may be, are as well off as possible. Using percentages is a better approach for that.” This is an assertion, not an argument. No reason is given. And indeed common sense suggests the opposite: that if the goal is to ensure that people who exist (all people exist, by the way) are as well off as possible, then surely we would want the incomes of the poor to increase to the point where they are not in poverty. This goal is served, not hindered, by focusing on the absolute number of people below $7.40/day.

6. “Neither Maddison’s GDP numbers or Bourguignon and Morrisson’s poverty rate extrapolations are thus as reliable as the World Bank data… Ultimately, this part of the debate is about what to do with incomplete data.”

No. The point is not just that the data is incomplete, although that is significant. The point (indeed the heart of my argument about the long-term numbers) is that GDP data cannot legitimately be used to assess poverty during a period of mass dispossession. If Matthews and Roser think this is just a debate about what to do with “incomplete data”, they are missing the point.

7. Here Roser makes a very strange argument: “For Africa we really don’t have many reconstructions,” he wrote in a message. “But you could also ask how much the uncertainty for Africa can possibly matter for our estimates of global poverty. The population of Africa was 8% of the world population. Even if all Africans at the time were billionaires this would mean that the global poverty rate would be at most 8% lower.”

If Roser admits that there is no data for Africa (and precious little for Asia and Latin America) prior to 1900, then why make a graph about “global” trends? Why not just be honest and say the long-term graph is mostly about the rise of GDP in the global North and leave it at that? Again, if you insist on “sticking to the facts”, then stick to the facts.

8. Roser says: “What is really frustrating about it is that [Hickel] publicly gives the impression we don’t really know [about long term trends], which given all I said … and economic historians said in hundreds of great research publications is absolutely not true.”

The “hundreds of great research publications” to which Roser refers are the publications that underlie the Maddison database. But – as I have pointed out before – these publications are about GDP, not about poverty, so they don’t help us address the question at hand. Roser’s point here completely ignores my core argument.

Now, we do happen to have quite a lot of research about what happened to people’s lives during enclosure and colonization, which illustrates a process of mass immiseration. I have listed some of that research in my posts, and have cited yet more in The Divide. Roser gives no indication that he has any familiarity with it.

9. “If Hickel argues that $1.90 a day is too low a bar to set for poverty, I’d counter that a definition of poverty that doesn’t include Malthusian conditions before industrialization is inadequate as well.”

By invoking “Malthusian” conditions, Matthews is repeating a story that he just assumes to be true. He hasn’t cited a single source for this claim. More importantly, though, Matthews gets his history exactly backwards. Malthus was writing about a population that had already been immiserated by enclosure in England. Their misery was not some prior, timeless condition but rather an artifact of the dispossession that paved the way for industrialization (see Ellen Meiksins Wood). Indeed, Malthus was a conservative thinker who believed, basically, that enclosure was good because it put poor people at the mercy of hunger and therefore made them work harder and become more productive (so as to increase the GDP) – the same argument, incidentally, that the British made when they dispossessed indigenous Americans, and later Asians and Africans.

It is not appropriate to use this lens to speculate about the living conditions of people prior to enclosure – whether in England or (even more obviously) the global South.

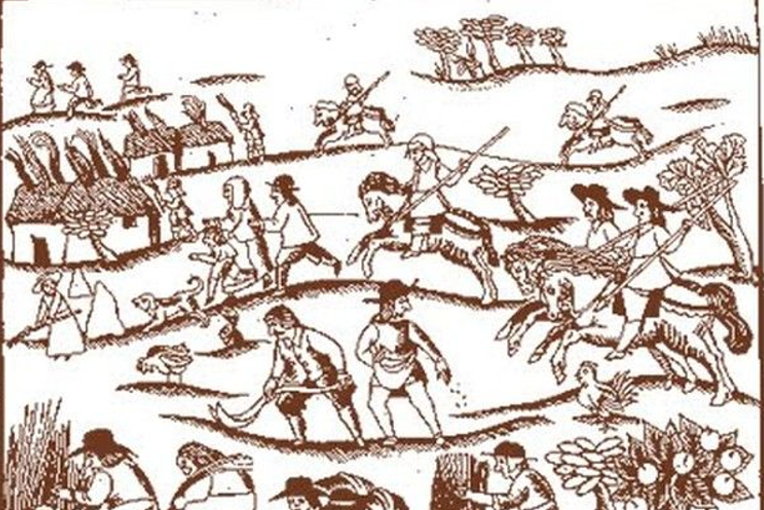

Teaser photo credit: English peasants responding to enclosure by becoming part of the Digger movement.