The Indigenous Peoples March in Washington, D.C. went viral online after a group of high school students from Kentucky mocked an indigenous Vietnam War veteran, Nathan Phillips, outside the Lincoln Memorial on Jan. 18.

The incident was indicative of the racial politics in the United States and around the world that devalues indigenous rights and sees indigenous peoples as caricatures meant for the amusement of the dominant classes. However, the significance of the march — which was organized by the Indigenous Peoples Movement, a global coalition of indigenous communities — extended well beyond this petty display of white supremacy.

“I look at this as the last stand of desperate people — they’re not going down without a fight,” said Cliff Matais, one of the organizers of the rally. Matais is the head of the Red Rum Motorcycle Club, an indigenous biker collective that volunteered to shepherd protesters from their starting point outside the United States Department of the Interior to the symbolic Lincoln Memorial.

Keith Anderson (WNV/Tekendra Parmar)

Protesters gathered outside the Department of the Interior for a 9 a.m. prayer before the start of the march. The smells of sweetgrass, sage and rosemary wafted through the air. “Be mindful of people’s sacred items” organizers told protesters, gesturing to the men and women dressed in their traditional regalia and carrying the drums and instruments of their people. Alongside the banners calling for the protection of indigenous lands and indigenous rights, some protesters carried family heirlooms as old as the founding of the United States. “These trade silvers are as old as the 1700s,” said Keith Anderson, a member of the Nansemond indigenous community in Virginia, pointing to the ornaments around his neck. As much as the march was a call for justice and human rights it was a celebration of the history and culture carried by each individual.

The march brought together a who’s who of indigenous activists, from radio personality Jay Winter Nightwolf to Ashley Callingbull, the first Canadian to win the Miss Universe pageant.

“Donald Trump has declared war on the American Indian,” Nightwolf said in a fiery speech overlooking the National Monument, as teenagers in MAGA hats loitered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Nightwolf’s speech was a reminder that in his first month in office President Trump steamrolled plans to build the controversial Dakota Access Pipeline, which had been rejected by his predecessor.

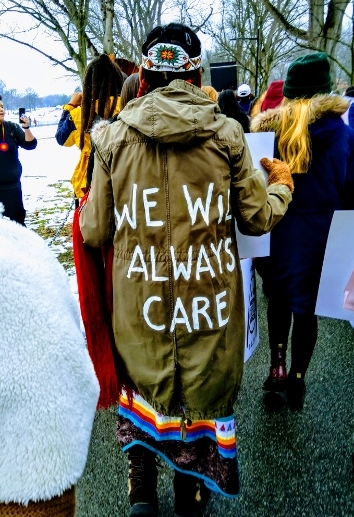

Yet, protesters rallied against Trump with banners like “There is No O’Odham Word for Wall,” referencing the indigenous community whose land the president’s border wall threatens to tear through. Another sign read, “There are no illegals on stolen land.” And perhaps the most penetrating of criticisms came from a woman who wore an olive green jacket with the words “We Will Always Care” written in white paint on its back — a reference to Melania Trump’s infamous “I really don’t care” jacket.

A woman wearing a jacket with the words “We Will Always Care” written on it. (WNV/Tekendra Parmar)

Donald Trump was not the only far-right politician on the minds of protesters. Others carried banners that read “The world knows what’s happening in Brazil. You are not alone. #StopBolsanaro.” Like Trump, during the first days of Jair Bolsanaro’s presidency earlier this year, he signed an executive order effectively stripping indigenous Brazilians of autonomy over their land.

From environmental and land rights to the thousands of indigenous women who have gone missing in the United States and Canada, the march was a reminder that indigenous people suffer from the same problems across the world and the necessity to build transnational solidarity.

“We have no tokenized leadership,” said S.A. Lawrence-Welch, the social media coordinator for the Indigenous Peoples Movement. “People want to have a name behind something. But it’s all of us. The idea that we have to separate ourselves to have an identity is part of the problem.”

According to Lawrence-Welch, the protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline that tore through the land of the Sioux at Standing Rock, was a watershed moment reminding indigenous communities of their capacity to build solidarity. Standing Rock brought together indigenous communities across North America for the largest Native American action since the American Indian Movement’s 71-day occupation of Wounded Knee in 1973.

“Because of how everything ended at Standing Rock — this is a space to heal and come back together and live in that power and resilience,” said Takota Iron Eyes, a 15-year-old environmental activist, who was at both protests and whose father, Chase Iron Eyes, helped organize the march.

For Phyllis Young, a veteran indigenous rights activist and member of the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, the march was also a reminder that the incoming Congress is the most diverse in American history. Among its members are Sharice Davids and Deb Haaland — two of the first Native American women elected to congress. (Davids also happens to be the first lesbian congresswoman from Kansas.) Both were strong supporters of the protests at Standing Rock.

“We’re here because, [they] came to Standing Rock to stand with us, now we’re on the Hill to stand with them,” Young said. “No arbitrary orange man is going to dictate by executive order … we’re here as a new partnership.”