Why do civilizations collapse? It is a question that has been haunting the nebulous entity we call “The West” from the time when Edward Gibbon published his “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” in 1776. The underlying question in Gibbon’s massive study was ‘are we heading for the same destiny as the Romans?’ A question that generations of historians have tried to answer, so far without arriving to answer on which everyone would agree.

There are, literally, hundreds of “explanations” for the decline and fall of empires, and the same confusion reigns for the fall of the past civilizations rising to glory and then biting the dust, becoming little more than ruins and footnotes in history books. Is there a single cause for these collapses? Or is collapse the result of many small effects that, somehow, gang up together to push the great beast down the Seneca Cliff?

One of the most fascinating interpretations of the collapse of civilization is Joseph Tainter’s idea that it is due to “diminishing returns.” It is a well-known concept in economics that Tainter adapts to the historical cycle of civilizations, focusing on the control structures designed to keep together the whole system, the bureaucracy for instance. Tainter attributes these diminishing returns to an intrinsic property of control structures to become less efficient as they become larger. Below, you can see a rather well-known graph taken for Tainter’s book “The Collapse of Complex societies.” (1988)

Tainter’s idea is fascinating for several reasons, one is that it generates some order in the incredible confusion of hypotheses and counter-hypotheses of the debate on societal collapse. If Tainter is right, then the many phenomena we observe during the collapse are just a reflection of an inner sickness of the society undergoing it. Barbaric invasions, for instance, are not the reason that led the Roman Empire to fall, the Barbarians just exploited the chance they saw to invade a weakened empire.

A problem with Tainter’s idea is that it is qualitative: it is based on the available historical data, for instance, the debasing of the Roman currency, but the curve of the diminishing returns is just drawn by hand. One question you might want to ask is: fine, there are diminishing returns, but where is the collapse in the curve? Another one could be: if the system experiences diminishing returns, why doesn’t it just retrace the curve to go back to where it was before?

These and other questions are examined in a system dynamics study that myself and my coworkers, Ilaria Perissi and Sara Falsini, performed. The idea is that if a civilization is a complex system, then it should be possible to model it using system dynamics, a tool specifically designed for this purpose. So, we built a series of models inspired by the concept of “mind-sized” models. That is, models that don’t pretend to be a detailed description of the system but try to catch the basic mechanisms that make the system move and, sometimes, go through tipping points and collapse. We found that on the basis of some simple assumptions, it is possible to produce a curve that qualitatively looks like Tainter’s one.

The system dynamics model tells us that the origin of the diminishing returns lies in the gradual depletion of the resources that flow through the system. It is not so much an effect of increasing complexity in itself, the problem is sustaining that complexity.

Then, the model also tells us what happens on “the other side” of the curve. That is, what happens if the system continues its trajectory beyond the point where Tainter’s curve stop. The curve shows a clear hysteresis, that is, it doesn’t follow the earlier path, but it remains always on a low-benefit trajectory. It means that cutting on bureaucracy doesn’t make the system more efficient.

These results are not the final word on the question of societal collapse. But they do provide some fundamental insight, I think. It is the fact that the system is “alive” as long as its resources provide good returns — in terms of energy resources, it means they have a good EROEI (energy returned on energy invested). If the EROEI goes down, then the system falls into the Seneca Cliff.

Of course, since our society depends on fossil fuels, we are bound to go that way because the depletion of the best resources is progressively lowering the EROEI of the system. If we want to keep alive some kind of complex society, we can’t do that by scraping the bottom of the barrel, desperately trying to burn what we can still burn. But, unfortunately, it is exactly what most governments in the world are trying to do. It is a good way to speed up toward the impending cliff.

What we should do, instead, would be to move as fast as possible toward a renewable-based society. We are lucky that we have energy technologies efficient enough in term of EROEI that they could support a transition to a better, cleaner, and more prosperous world. Too bad that nobody seems to want them.

There has to be something in the concept of “BAU” that makes it one of the most powerful attractors you can simulate in a system dynamics model. And so we are moving toward an uncertain future, but one thing that we can be sure of is that fossil fuels will not accompany us there.

_______________________________________________________

Our complete paper can be found here. You can also find an abridged version on ArXiv.

And here are the authors

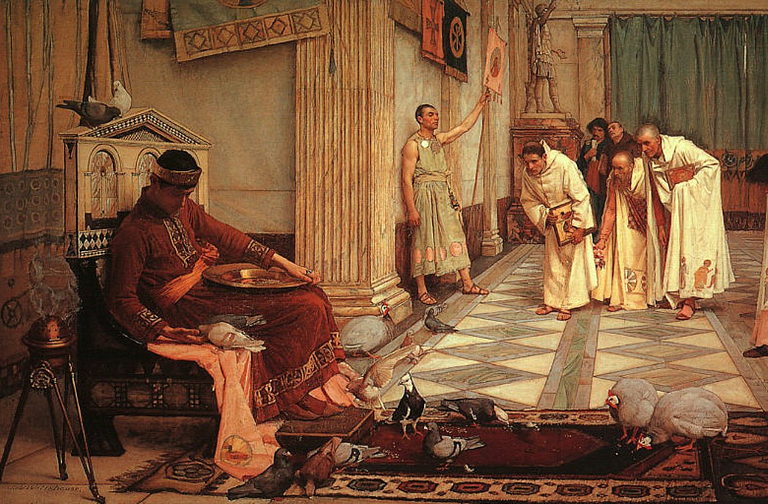

Teaser photo credit: The Favorites of the Emperor Honorius, by John William Waterhouse