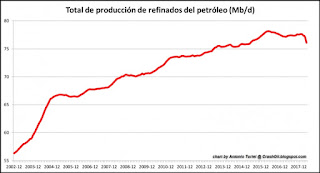

In a recent post, Antonio Turiel proposed that the global peak of diesel fuel production was reached three years ago, in 2015. Turiel’s idea is especially interesting since it takes into account the fact that what we call “oil” is actually a wide variety of liquids of different characteristics. The current boom of the extraction of tight oil (known also as “shale oil”) in the United States has avoided, so far, the decline of the total volume of oil produced worldwide (“peak oil”).

Shale oil has changed a lot of things in the oil industry, but it couldn’t avoid the decline of conventional oil. That, in turn, had consequences: shale oil is light oil, not easily converted to the kind of fuel (diesel) which is the most important transportation fuel, nowadays. That seems to have forced the oil industry into converting more and more “heavy” oil into diesel fuel but, even so, diesel fuel is becoming gradually more scarce and more expensive, to the point that its production may have peaked in 2015. In addition, it has created a dearth of heavy oil, the fuel of choice for marine transportation. In short, the famed “peak oil” is arriving not all together, but piecemeal — affecting some kinds of fuels faster than others.

Shale oil has changed a lot of things in the oil industry, but it couldn’t avoid the decline of conventional oil. That, in turn, had consequences: shale oil is light oil, not easily converted to the kind of fuel (diesel) which is the most important transportation fuel, nowadays. That seems to have forced the oil industry into converting more and more “heavy” oil into diesel fuel but, even so, diesel fuel is becoming gradually more scarce and more expensive, to the point that its production may have peaked in 2015. In addition, it has created a dearth of heavy oil, the fuel of choice for marine transportation. In short, the famed “peak oil” is arriving not all together, but piecemeal — affecting some kinds of fuels faster than others.

Turiel’s proposal has raised a considerable debate among the experts, with several of them challenging Turiel’s interpretation. Turiel himself and Gail Tverberg (of the “our finite world” blog) discussed the validity of the data and their meaning. Below, I reproduce the exchange with their kind permission. As you will see, the matter is complex and at the present stage it is not possible to arrive at a definitive conclusion. In my personal opinion, I would say that it is understandable that many of us are afraid of being criticized for having called wolf too early, but that it is nevertheless worth reporting one’s data and discuss them on the basis of what we know. Then, as attributed to John Maynard Keynes, “When I have new data, I modify my conclusions. What do you do, sir?”

________________________________________________________________

Gail Tverberg

Dear Ugo,

I don’t know if you have noticed, but data by type of refined fuel is available from various standard sources of energy data. EIA data has a lot of detail data for the US; BP has regional data for a number of breakdowns. There are no doubt other sources for oil consumption by country. I think of JODI as voluntary data; it is not really clear (to me) which countries are in or out, for which periods.

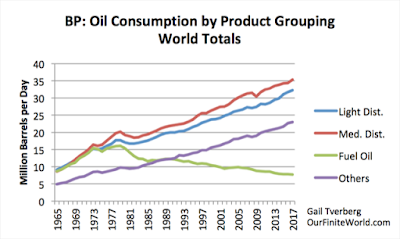

The information you are showing in your recent post seems to show a fairly different pattern from what BP shows (Dist. means Distillates).

According to BP, Middle distillates consist of jet, heating kerosenes, gas and diesel oils (including marine bunkers).

Within Medium Distillates, there is a further breakdown for recent years, showing a category called diesel/gasoil separately from jet/kerosene. It shows a fairly similar pattern.

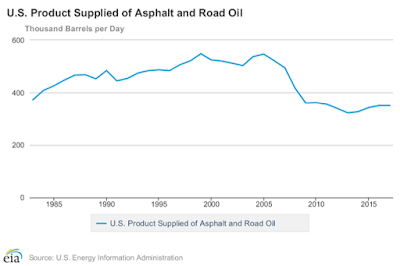

It is the “fuel oil” category, which seems to be the heavy distillates, that shows the big downturn in consumption. This is consistent with what we see in the US. Refineries can make a lot more money if they crack heavy oil and refine it into lighter products than if they sell it in close to the unrefined state. In the US, much road construction has changed from asphalt to concrete. Concrete is a coal product in some parts of the world.

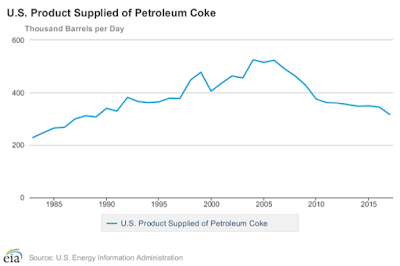

In the US, petroleum coke has also shown a big downturn.

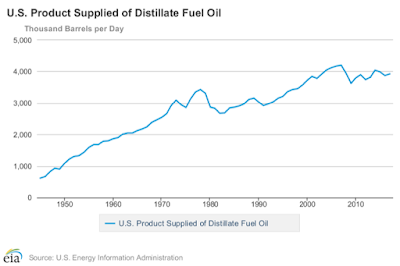

With respect to what EIA calls distillate fuel oil (which I think of as diesel), in the US, there indeed were two big steps down.

The first downturn in consumption, in 1981 (when interest rates were raised), was when a lot of home heating and also electricity generation was switched from diesel to other energy products. The second downturn occurred in 2008, when even more homeowners switched away from using diesel for home heating. Also, on the industrial side, some new techniques were developed for drilling oil wells, using natural gas instead of diesel. Natural gas is usually produced in the same field, and is much cheaper for oil producers to use, rather than purchasing diesel. Note that the percentage downturn is far smaller in the “distillate fuel oil” chart than for the other two EIA charts I showed.

To me, it is very difficult to figure out exactly what is happening, with such similar names for different products. Also, there seems to be a lot of shifting of use around the globe. All of this makes the situation confusing.

You might want to backtrack a bit on what you said about diesel. The evidence doesn’t seem as strong, looking at other sources. Perhaps a different post, looking at some new data as well, would be in order. BP data can be downloaded from this link: https://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/energy-economics/statistical-review-of-world-energy.html The tab you are interested in is Oil – Regional Consumption.

Best wishes,

Gail

___________________________________________________________________

Antonio Turiel

Dear Gail,

As for any other peak, some years must be spent to be completely sure that we have passed them. So any evidence so far must be taken, always, with a bit of caution, and in that sense I agree with your warning.

Regarding data, I prefer to use JODI because JODI data is better grounded than EIA data – EIA data contains a lot of “inference”, typically spawning from six months in the US up to a couple of years in other countries. JODI data, on the contrary, tend to be more timely (and when there are significant time lags these are reported). Notice also that EIA, IEA and BP use JODI data as one of their sources.

Another significant difference is that in your first graph you represent consumption, while I always represent production. The difference is significant, as I am mainly interested in the refinery throughput because this is the problem I want to characterize (the difficulties to increase the output). The use of stored stuff explains the difference between both.

Some readers have pointed out that the slowdown and even decrease in diesel production, if real, could be a consequence of a lowering demand. This is the same situation as for peak oil: you can always argue that there is not enough demand for that oil, and it is true in any instance: the problem is one of affordability, as you have explained many times.

Regards,

Antonio

__________________________________________________________________________

Gail Tverberg

Hello Antonio,

I think that there is a real difference between the kind of data a person wants to look at when that person is examining the indications for an individual country or a subdivision within a country and the information a person wants to look at for world level indications.

When a person is looking at detail level data, then I agree that there is very often a big difference between production and consumption. Looking at data such as JODI data, along with other indications, can be helpful for putting together the true indications for that small grouping. A person has to be pretty aware of particular patterns for individual countries or other smaller groupings. I know, for example, that Texas shale oil data seems to be reported much more slowly than North Dakota shale oil data. Some countries are notorious for trying to exaggerate their production. This is why OPEC shows two sets of numbers, in its monthly reports: “from secondary sources” and “as reported by the producer.” The “from secondary sources” numbers are generally viewed as the more accurate ones.

When a person is looking at small segments of data, corresponding more or less to how the data is reported, then it is fairly easy to see major mistakes. For example, does it look like the “diesel” (or some other grouping) accidentally got reported as “fuel oil,” for some period of time? Does it look like some categories are simply missing, or the amounts have been misinterpreted? If I am looking at detail data, then I can look for mistakes. By the time aggregations occur, the big problems, like missing whole sets of data from some small countries, will be difficult to see. If I am looking at aggregate data, especially on a world basis, I really want someone to have looked at the data in detail, and to have figured out what pieces were missing. They have no doubt made some estimates of the missing pieces, but if I am making estimates of trends, making estimates of the missing pieces is absolutely essential.

I personally have no experience working with JODI, but I have worked with an awfully lot of other data sets (in the insurance world previously, and now in the energy world). I am very much aware of the fact that the initial coding is likely to have a lot of flaws, especially if it is voluntary, and doesn’t have to balance to published financial data.

There is indeed some difference between production and consumption, but when we get to a world basis, they mostly offset. For the purpose of determining trends, what we want is well-massaged data–data that is as free from errors and omissions as possible. I would be willing to believe EIA, IEA, or BP data for this purpose. I would much prefer using well-massaged consumption data to look at trends, rather than a summation of individually reported data of questionable validity.

I have at least a little background on what is happening. I know that there is a fair amount of flexibility in the distribution of finished oil products that can be obtained from a barrel of oil. In general, it is possible to “crack” long hydrocarbons to make shorter (and thus lighter) hydrocarbons; it is close to impossible to go from short chains to longer chains. I was involved in discussions in 2008, when oil companies wanted to increase the refining of what had been products such as asphalt and petroleum coke, because, with high oil prices, oil companies could make a much larger profit from refining heavy oil into higher-price products such as diesel and gasoline. Concrete could be substituted for the asphalt. The US has a natural advantage in cracking long molecules because it has an abundant supply of low-cost natural gas. That keeps the cost below what a similar process would cost in Europe. Heavy oil, such as that from the oil sands, also tends to sell at a substantially lower price than light sweet oil, making the process profitable in the US under a range of price scenarios.

When I see two different trends, one in the JODI data and a different one in the BP data, I am inclined to believe the BP indications.

A Different Diesel Problem

I think that Europe may have a different diesel problem than the one you are thinking about. Europe has tended to use diesel to power its private passenger automobiles as well as its trucks. This is an awfully lot of “demand” to put on one segment of refined products from a barrel of oil. The US and many other countries have spread out demand, with private passenger automobiles using gasoline, instead of diesel. This allows for demand to match up better with what comes out of a barrel of crude oil. According to BP data, in 2017, Europe consumed 7.7% of the world’s gasoline supply and 24.4% of the world’s supply of a subcategory it calls diesel/gasoil. (These are subcategories for recent years that I don’t show on the chart above.) I suspect that there is no oil, anywhere, that could be refined to provide the overly heavy diesel mix that Europe requires. No one in Europe stopped to think, “If cars and trucks both run on diesel, we will need to import an awfully lot of diesel from the world market. We are asking for problems. If the world has barely enough to go around, our demand will raise world diesel prices.”

At this point, there is no sense in adding a whole lot of refining capability for heavy oil in Europe; Europe lacks the cheap natural gas to process it. The same BP report mentioned previously also shows data on Europe’s refining capacity and its refinery throughput. Refining capacity and throughput both seem to be falling, as available North Sea oil falls.

Best wishes,

Gail Tverberg

_________________________________________________________________

Antonio Turiel

Dear Gail,

Sorry for my late response – I’m presently attending an important conference in Rome, and the previous days I was very busy preparing my presentation.

Regarding your comments, if I understand correctly your point, you prefer EIA, AIE and BP data as they have better quality, apart from the fact that they integrate diverse sources of data. The key point is that they apply a better quality control and the result is, let’s say, better.

This is a reasonable point, but something that I anyway call into question: are those data really better? As a matter of fact, both EIA and IEA suffer political pressures to make up their data, and this kind of thing is much worse than having an error: it is a bias. Random errors (unexpected data failures, data flow interruptions, occasional double accounting, etc) do not really change the trend, just increase data volatility, something that can be compensated by for instance averaging (e.g., the sliding window of 12 months we apply). But biases can change trends, and that’s is quite crucial.

Your point is that maybe what is called diesel has changed along JODI series, something that I am not absolutely aware of, and in fact such a “sudden removal” of diesel from that category should result in an increase the other middle distillates, the “Other fuel oil” category, which is not the case. Besides, removal as such typically shows up as steps in the graph, something that is not observed either. So such hypothesis seems to me very unlikely.

Coping with noisy data with unknown uncertainties is something physicists are used to do, because this is our bread and butter (data from the real world are always noisy and uncertain).

So let me tell you what I propose to solve this issue:

I’m a specialist in a technique called “Triple Collocation” that allows an intrinsic characterization of errors and biases of three sets of different measurements of the same physical quantity. Therefore, abusing of your kindness, if you could provide me different data series of data of what you could name “diesel” or “medium distillates” or whatever you feel more confident of (or even better, all of them!), from different data providers you trust the most (EIA, IEA, BP, whatever) and I will include the data from JODI and make all possible triples (if we have EIA, IEA, BP and JODI we have 4 possible triplets), I can estimate the calibration factors, biases and standard deviations of the random errors for each triplet, then compare the 4 possibilities to see if the results are consistent.

This exercise could be very informative for all us and provide a better insight about where we actually are right now.

Regards,

Antonio