Transcript of Daniel Wahl’s ‘Findhorn Talk’ on Human and Planetary Health: Ecosystems Restoration at the dawn of the Century of Regeneration; October 13th, 2018

I like starting with this slide of planet Earth because it shows the atmosphere and how thin that layer of life — of biosphere — actually is. Within it we take our home, within which everything, every love, every war, every bit of human history has taken place.

There is not a thing that you and I can do that does not affect the health and wholeness of this place. Unfortunately we have come through centuries, if not millennia during which we have not been very wise about how to behave within that living planet.

We are now in an age that some people like to call the anthropocene — we have become a geological force, we are shaping the planet, have an enormous impact on biodiversity, on climate change and all these issues.

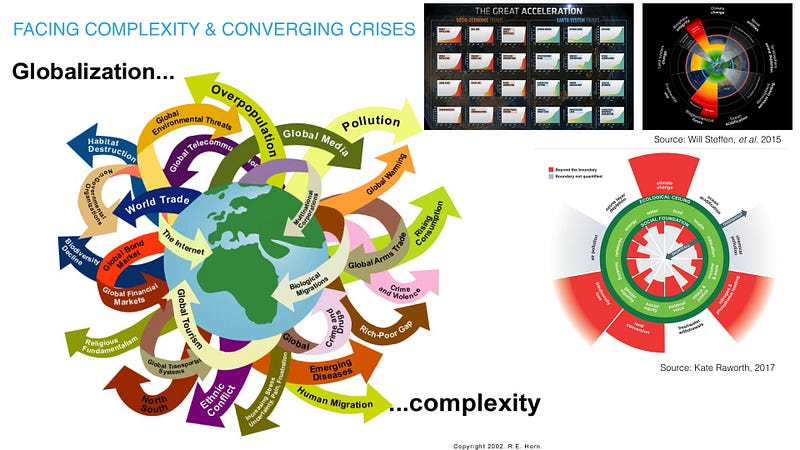

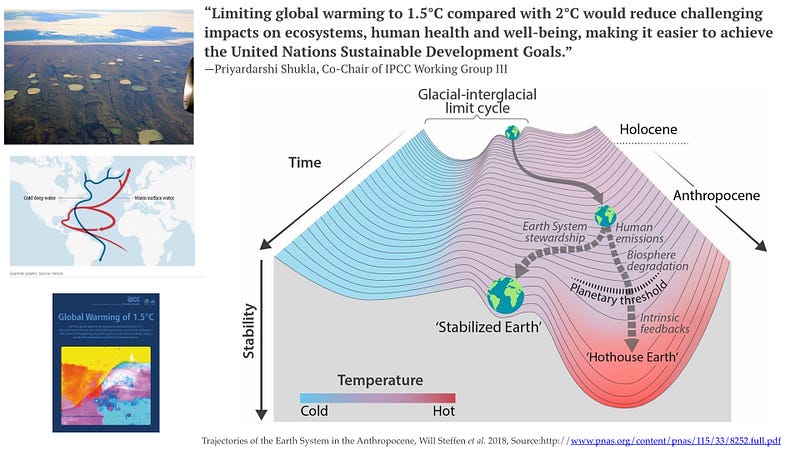

These slides might be familiar to some of you. This is the planetary boundaries graphic [upper right corner of image above]. It shows that we are already beyond certain planetary boundaries, that if we don’t draw back within the safe limit of these planetary boundaries we might not have a future.

There are lots of things coming together, economic crises, ecological crises, social crises. My friend and mentor Fritjof Capra once said if you follow the rivers of these crises upstream, you meet a crises of consciousness, a crises of perception. A crises of how we see our selves and our role in this living planet.

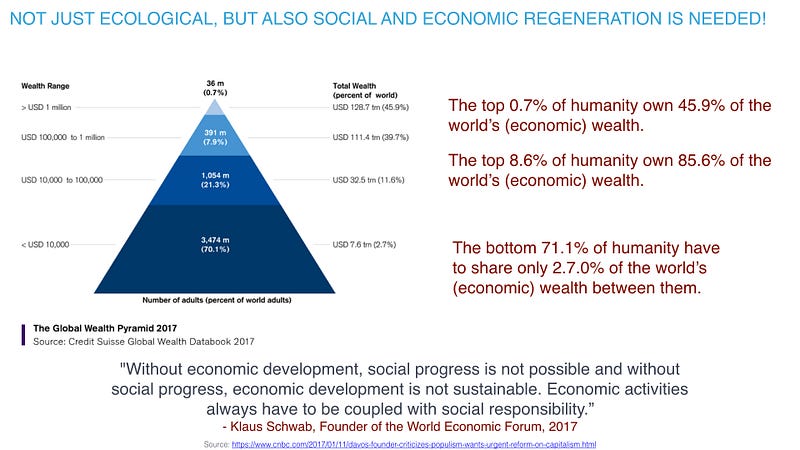

Also: We live on an incredibly unequal planet. If you sum up the two top layers of this graph produced by Credit Suisse every two years, 8.6 percent of humanity own 85.6 percent of the wealth — which is staggering. What is even more staggering is that 71 percent of humanity have to share 2.7 percent of the wealth.

We cannot create a sustainable planet — or a sustainable future for humanity — with this inequity. And, we wouldn’t want to sustain a humanity that is that unequal.

Just at the beginning of this week, the IPCC — the panel of climate change — released another report saying while we are completely off-target regarding what was agreed in Paris — with a two degree target — it is actually not enough.

We need to radically reduce carbon emissions and actually do more than that. We need to reverse carbon emissions to avoid ‘hot house Earth’. We are on this path (see slide aove) and if we don’t manage to take the detour onto this semi-stable ledge, we are dropping into this abyss.

About two weeks ago the Secretary General of the United Nations said that we have about a year and a half to take drastic action. The IPCC report — again very conservative — is talking about 12 years.

I actually think that we are already in the middle of what is called run-away climate change. That image up there with the lakes. That is the permafrost melting. These lakes are bubbling like a little soda pop off-gasing methane. The circulatory currents in the oceans are slowing down. …

We are basically faced with a run-away cycle now, where climate change is getting worse even if we are starting to paddle back. So even if we do all the things that I am going to be talking about this evening, we are facing three decades of collapse.

That collapse is the collapse of an old system that no longer serves, that we have to go through in order to give birth to a new humanity that sees itself again as part of the community of life. So even if we get things right we will still face three decades of quite severe upheaval.

We need to go upstream and look at this ‘crisis of perception’. We need to start rethinking the story of who we are and why we are here. We need to start thinking about what we could do if we actually lived in a way that is: “creating conditions conducive to life.”

Janine Benyus, the founder of the biomimicry work, says “Life creates conditions conducive to life.” This is in nutshell what we should be doing. I would also say that life is a regenerative community (1). We need to rejoin that community.

To do that we need to change the stories we tell about ourselves and we need to change the ‘organizing ideas’ that shape our perception. What do I mean by that? Have a look at that [the image below].

Some of you are seeing the head of an animal, others are seeing only a black and white circle with black dots in it. — If I give you the organizing idea ‘head-of-a-giraffe’. Ahh — some people go ‘ohh, I can see it now’. This is the neck, these are the horn, these are the eyes, this is the snout. She is looking down this way [from center line to bottom right of the circle].

This is just to show that organizing ideas are incredibly powerful. We don’t see things because they are out-there and they just come-in. We see things because we have ideas about what is out-there and we make the world. We bring forth a world together in conversation. That is the power of reshaping the world for us as well.

One of the big stories that we have been told is that life is all about survival of the fittest, the struggle for survival on a planet with scarce resouces. — That is not true. — Life is a process that acts through diversification and subsequent integration of that diversity at higher levels of complexity. More often than not this is done through new forms of collaboration.

This is what we are challenged to do now — we have to! And, it seems impossible if we watch the news. In Brazil, in the USA, in so many places we seem to be going in exactly the opposite direction. But we have to — let this one sink in: we now have to do the impossible, because the probably is unthinkable and unconscionable (2).

So maybe it is good to be here at Findhorn where one of the tag-lines is often ‘expect a miracle’. We need one!

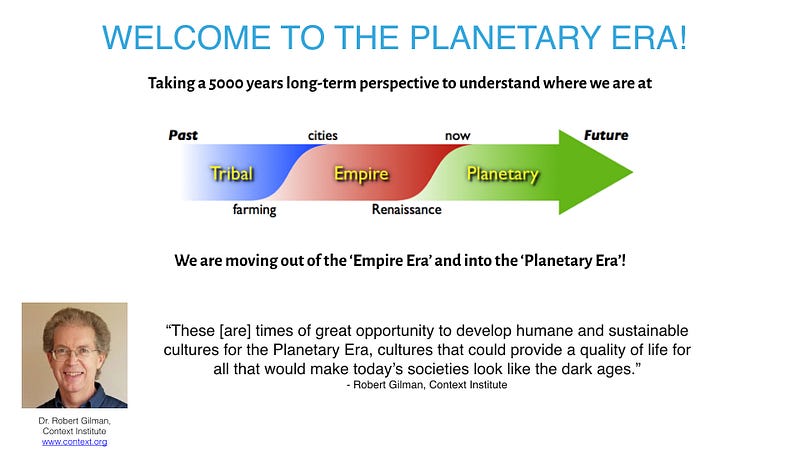

Another good friend of this community — Robert Gilman — sketches it out in this way. He talks about the ‘tribal era’ that humanity went through. Then with the onset of agriculture — which to some extent was also the beginning of humanity starting to exploit the planet in a way that was not very wise — we became able to settle and the ‘era of empires’ started.

We started to build cities. We started to create nations and empires that went to war against each other. So — we began a war against nature and in doing so began a war against ourselves. — And then, Robert speaks about humanity moving into the ‘planetary era’ (3).

What I like about this graph[above]: in many ways, it seems that with the beginning of the Renaissance we enabled the ‘scientific revolution’ and a new kind of technology was made possible that made it also possible to destroy the planet much faster. At the same time — through science — the same science that gave us these destructive technologies also gave us an understanding of being part of this living planet.

This transition out of the era of empires into the planetary ear — to us with our 70, 80, 85, 90 year lifespan — seems very long; but really it is short for a complete transformation of our civilizational presence in Earth. And — that sometimes gives me hope: that we are at the end of the long transition era and that what seems like ‘nothing is moving’ is actually part of a larger process.

So we are moving into the planetary era.

This is me in 2006 just before I moved to Findhorn. The two large books I am holding in my hand are volume one and volume two of my PhD thesis: ‘Design for Human and Planetary Health: A Holistic / Integral Approach to Complexity and Sustainability’. Sounds very academic!?

What is amazing [to me today] about this, is when I finished the PhD I could not find any post-doctoral research grants, nobody wanted to fund me because my work was too trans-disciplinary. I was sent from one funding council to the other. So I kind of put my PhD in a drawer and came to Findhorn. … In those days it was good to hide your PhD. There was a bit of an attitude, that if you had a PhD you were in your head so you could not be in your heart and you probably weren’t spiritual. […] I don’t think it is like that!

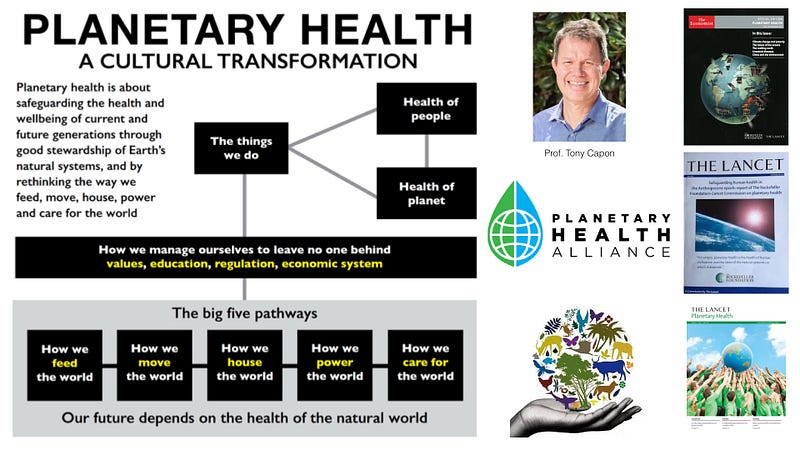

Just recently, this summer, I had a phone call from Anthony Capon — a professor at the University of Sydney — who said he was going to be in Europe and between two conferences he had some time and would love to come and see me on Mallorca to talk about my work. I said, yes, sounds interesting, let’s meet. He is a co-author of a report that came out in 2017 by the Rockefeller Foundation and The Lancet — the top medical journal — that is called ‘Planetary Health’.

This whole meme of ‘planetary health’ has grown enormously over the last years — and I was not actually aware of that until I saw the report had been published. There is a whole field of medicine now that understands that there is a deep link between ecosystems health and ‘planetary health’.

Health actually is — and this comes from my PhD — an emergent property of complex dynamic systems at different levels of scale. So a healthy cell sits in a healthy organ in a healthy body in a healthy family in a healthy community in a healthy bioregion in a healthy ecosystem on a healthy planet. And of course it goes the other way around. If we do anything that is unhealthy at any of those levels it affects health at all the other levels.

I came to work on planetary health using a different name [under the framework of regeneration]. A couple of years ago I published a book called ‘Designing Regenerative Cultures’ because the idea of regeneration is also about health. Resilience is also about health.

The title of my book harbours a — somewhat — paradox. On the one hand we need to redesign the human presence on Earth, and on the other hand cultures aren’t designed, cultures emerge out of the interactions that we have with each other — through the stories we tell.

I have learned from one of my mentors at Schumacher College that “if you step on a paradox, you can be sure to have some truth on your shoes”. Life is much more complex than linear either/or thinking. So when we work with paradoxes we get closer to what truth is actually about.

In writing this book — very early on I realize, asking myself ‘what can I write in this book that would actually be meaningful in ten, fifteen years, twenty years time’ — I realized that most of the solutions that human beings have created for themselves and for future generations were created with the best of intentions. Nevertheless, so many of them have turned into today’s problems.

So yesterday’s solutions turn into today’s problems. Who are we to think that our sustainable, regenerative, green — or what ever you want to call them — solutions will not turn into problems later on? Maybe we have got it wrong as a culture? Questions that aren’t transient are means to get to better answers. Maybe answers and solutions that are transient are means to help us ask better questions?

Maybe a wise culture — when you try to create a compass that you can hand from one generation to the next — would actually create a set of questions to give to the next generation? How to we fit in? Who are we obliged to? Why are we here? Where are we going? What is this all about? These questions need to find new ways of making meaning.

My mentor David Orr once floored me with a question, saying “Daniel before we can find the answers to the questions of the how and the what we might have to do in order to create a sustainable human presence on Earth, we have to ask ourselves a much deeper question. And that questions is: What is it about Humanity that is worth sustaining?” — And if we find an answer to that question then we might learn to live into the future in a wiser way.

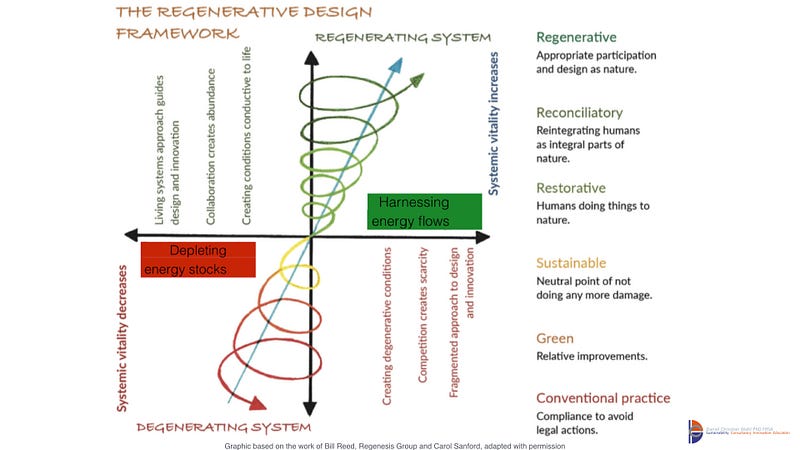

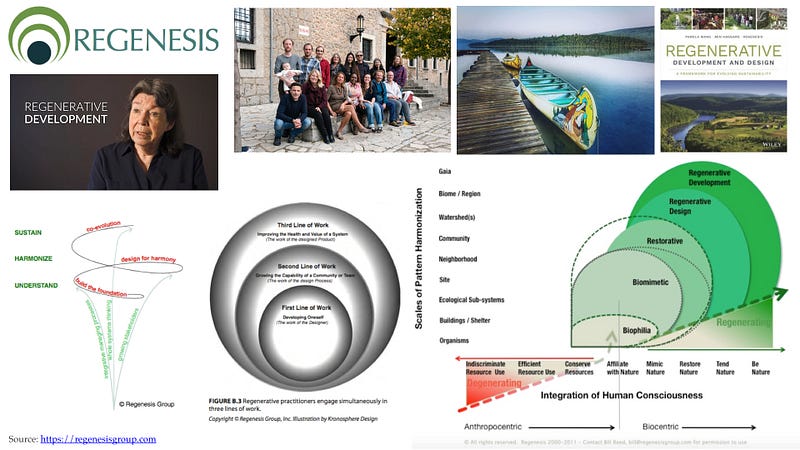

Very briefly, what do I mean by regenerative? This spectrum [below] is from a friend of mine, called Bill Reed, who works with a group called the Regenesis Group. It has also been influenced by a woman called Carol Sanford. Basically, there is a spectrum from ‘business as usual’ to ‘green’, which means doing things a little bit better, polluting a little less, using a little more renewable energy — which is part of the journey.

Then we get to ‘sustainable’ which means no negative impact, not adding any more damage. But because we have done so much damage we need to do more than that. So then you move into restorative, which can still be practiced in a mindset that views humanity as having power over nature — perpetuating the separation between man and nature. I am saying ‘man’ on purpose, because they have created most of the mess. This can lead to efforts like, for example, a large scale reforestation with eucalyptus in an already water-stressed area. They look very nice for 10 years or so and then they all die, because we ‘engineered’ an ecosystem.

So once we do the reconciliatory step and shift the organizing idea to that we are actually nature — that we can design as nature because we are nothing but it: biological beings first and foremost — then we move into working regeneratively.

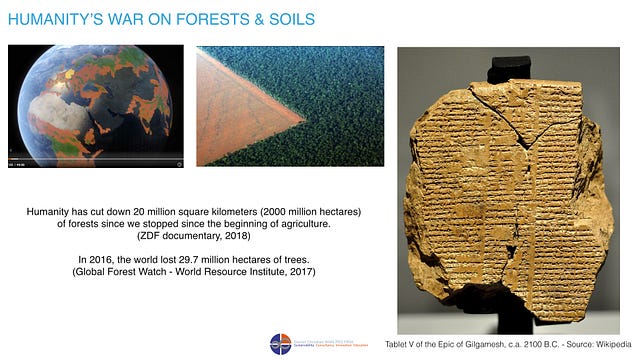

The oldest written story of humanity is the Epic of Gilgamesh. It tells the story how Gilgamesh was told by Humbaba, the forest god, that he was the all-powerful king but he was not allowed to cut down the Cedars of Lebanon. What did he do — the arrogant ______, I won’t say the word — he ordered himself a Cedar-palace, killed Humbaba and cut down the forest.

A modern ecologist would call this downwind desertification: Humbaba’s curse was that if you cut down the forest, your rivers will run dry, your soil will go salty and your empire will crumble. That’s precisely what happened [with the once fertile garden of Eden of the so-called ‘Fertile Crescent’].

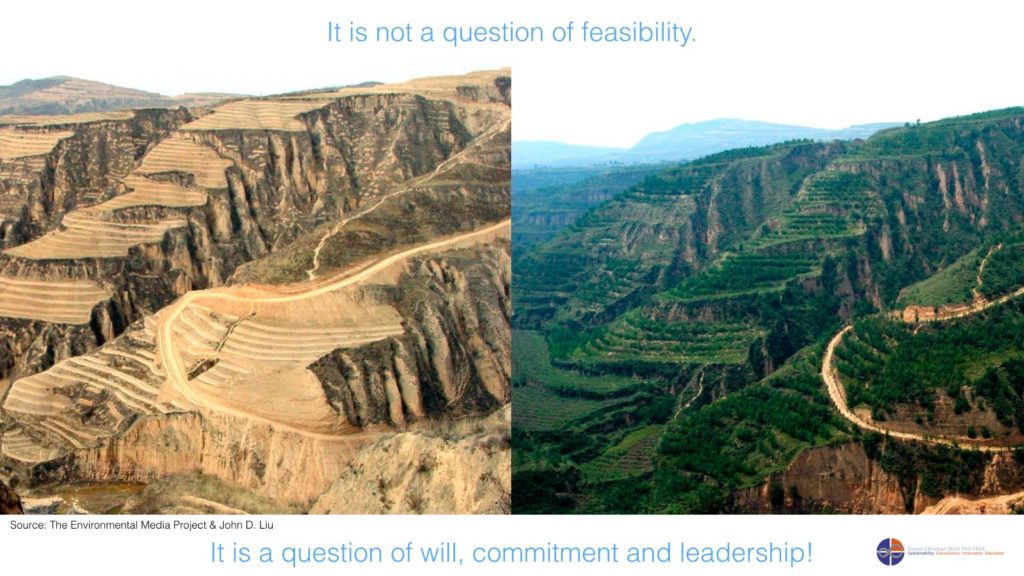

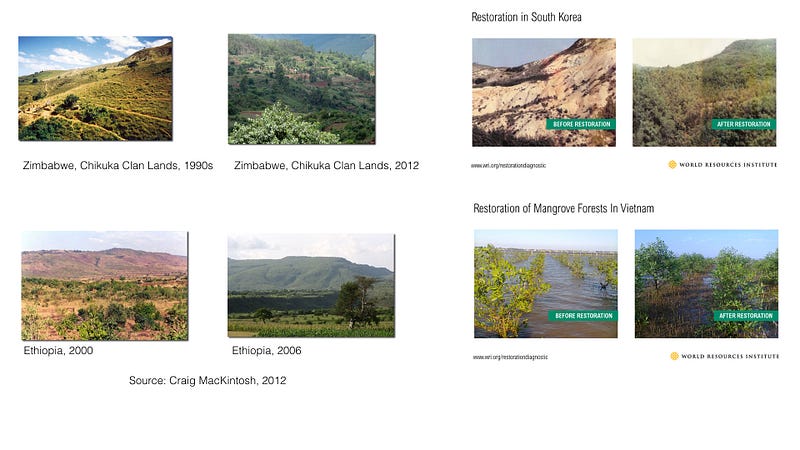

So we need to go from this.

To this:

And, it is possible!

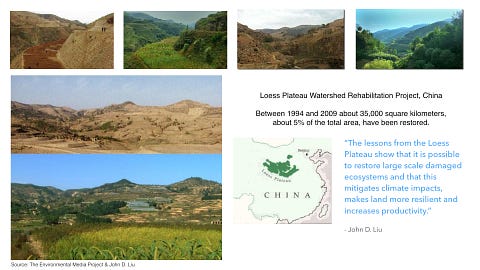

These [above] are pictures of the Loess Plateau in China. John D. Liu, who was here at Findhorn for the New Story Summit, documented this change. Over fourteen years the Chinese managed to turn an arid desert into a fertile and productive landscape. These are also all images from that area [below].

It is a very large area South-East of Beijing. We are talking thousand of square kilometers.

We can heal the planet. We can heal ecosystems. We can fit back into the community of life and create — bioregion by bioregion — a more abundant place. We can move from competitive scarcity to shared abundance.

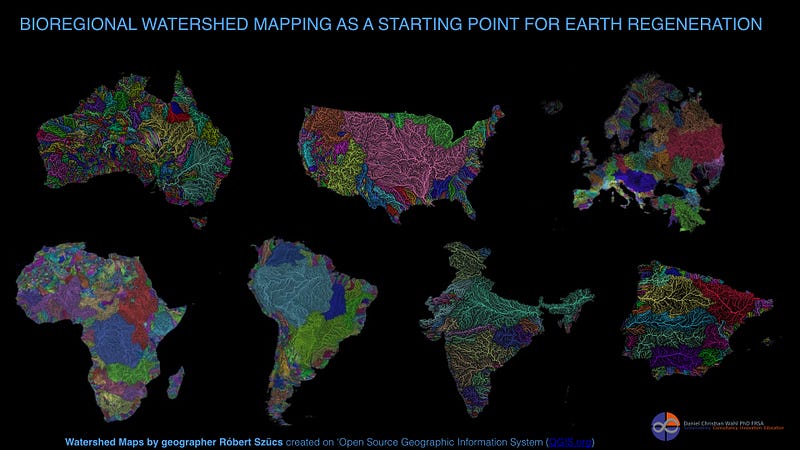

These [below]are wonderful images created by a geographer called Robert Szúcs who basically maps the river-systems of the planet. Once we start moving into a bioregional world — regenerating bioregion by bioregion — these kinds of maps will be very useful.

The bioregional approach fits humanity back into natural patterns rather than the other way around.

This was an event that I helped to organize at the Commonwealth Secretariat in London. Baroness Patricia Scotland, the Secretary General of the Commonwealth Secretariat that has an advisory role to 53 governments who together represent over 2.4 billion people, most of them are under 30 and a lot of these countries are in the front lines of climate change.

Baroness Scotland is fully behind this idea of regenerative development. We brought key practitioners of regenerative development from all over the world together. It has been a slow process to defined what exactly has come out of that meeting in terms of moving forward, but a lot of people met there and started to collaborate afterwards.

What has directly come from this process is this platform called ‘Common Earth’. It’s aim is to offer advice to Commonwealth countries on how to do regenerative development, as well as, showcasing best practice examples.

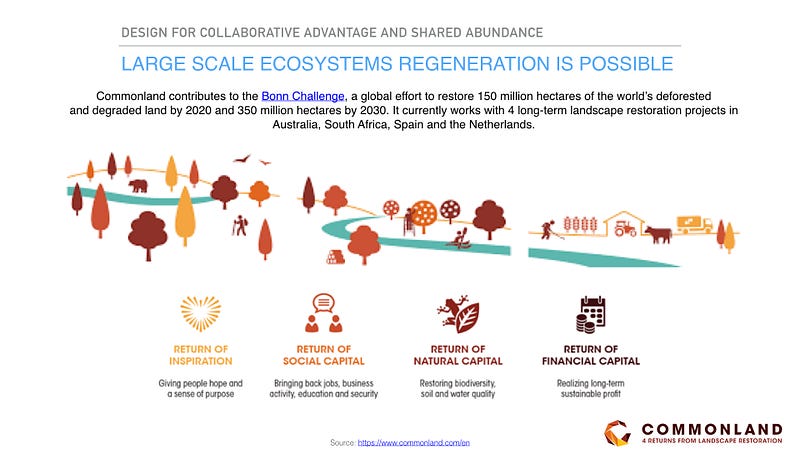

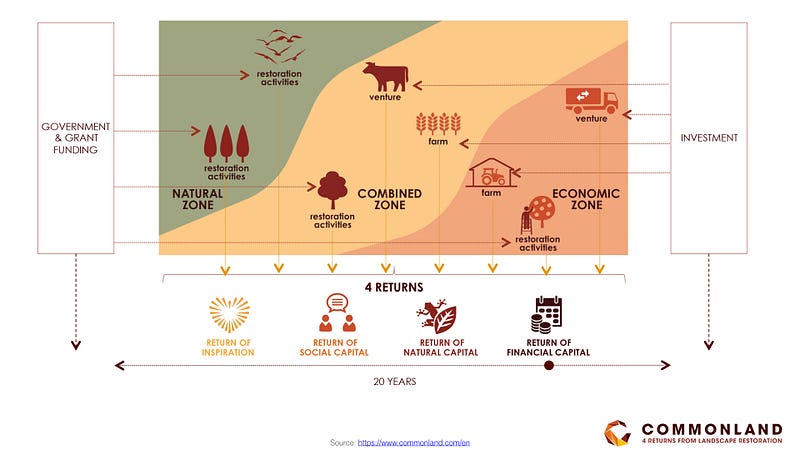

There is an organization in the Netherlands — called Commonland — that developed a strategy to finance large scale and long term ecosystems restoration and how to make it viable.

See more on the Commonland website]

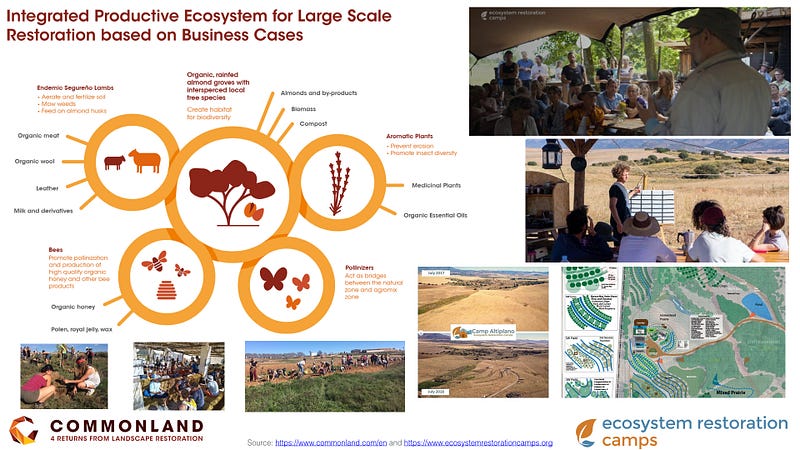

Commonland has set up four pilot sites around the world where they are working with regional landowners to transform entire regions. One of them is the altiplano near Murcia in Spain. The guy I mentioned earlier, John Liu, who documented the change at the Loess Plateau, has started an organization called the ‘Ecosystems Restoration Camp Foundation’ and the ‘Ecosystem Restoration Camp Cooperative’. Their work is basically to invite young people — or anyone — from around the world to come and learn how to become restorers of ecosystems in that place.

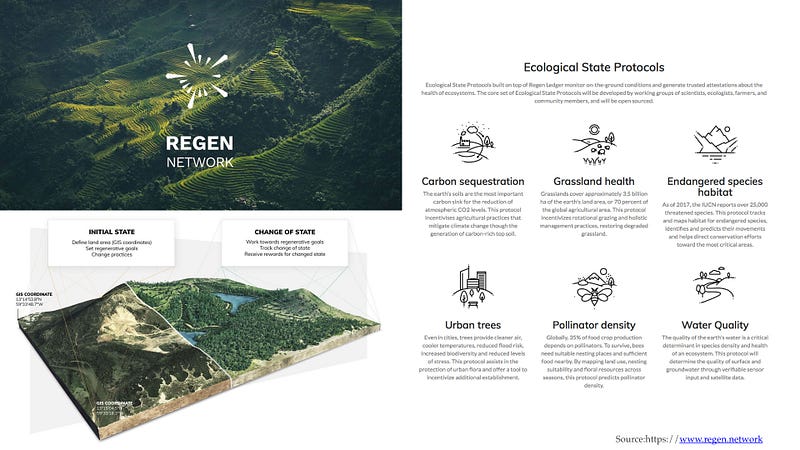

There is an organization call the Regen Network, who are working on using remote satellite images as well as sensors on the ground to really look at the before and after of regenerative work. Once you can quantify and prove that you have had a regenerative effect there are ways of finding funding linked to that. The Regen Network is also working with block-chain technology and crypto-currencies (liquid tokens) to create large funding streams to support regenerative practice.

These are more images of how they are doing the short and long term impact analysis and monitoring.

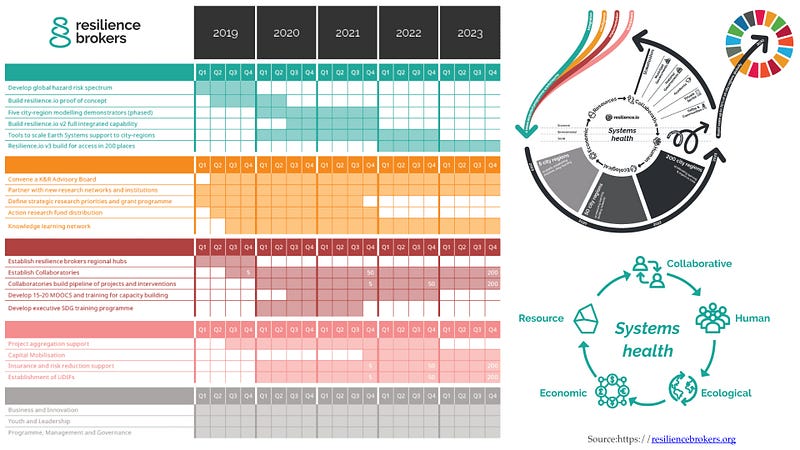

Peter Head used to run Arup Engineering, working on a lot of the early eco-city projects in China. He has now set up an organization called Resilience Brokers. They are starting an ambitious programme next year to by 2023 have worked with 200 city-regions around the planet to build resilience based on this shift towards a more bioregional biomaterials economy that supports the regeneration of ecosystems.

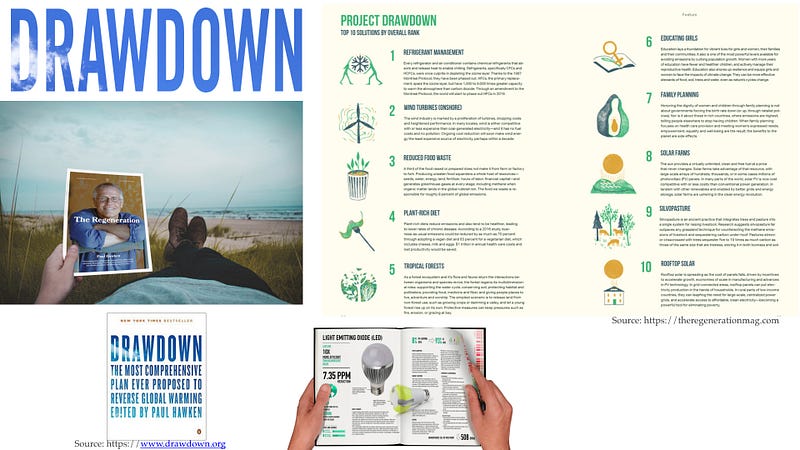

You have probably heard of Project Drawdown. The book and project set up by Paul Hawken, who also lived for some time in the Findhorn community. Project Drawdown has identified 100 proven strategies of how to draw down carbon out of the atmosphere.

This is beyond just carbon. We should not have carbon myopia, but right now we are faced with the challenge to stop cataclysmic run-away climate change. The techniques advocated by Project Drawdown are proven and some governments are now beginning to roll out programmes to work on this.

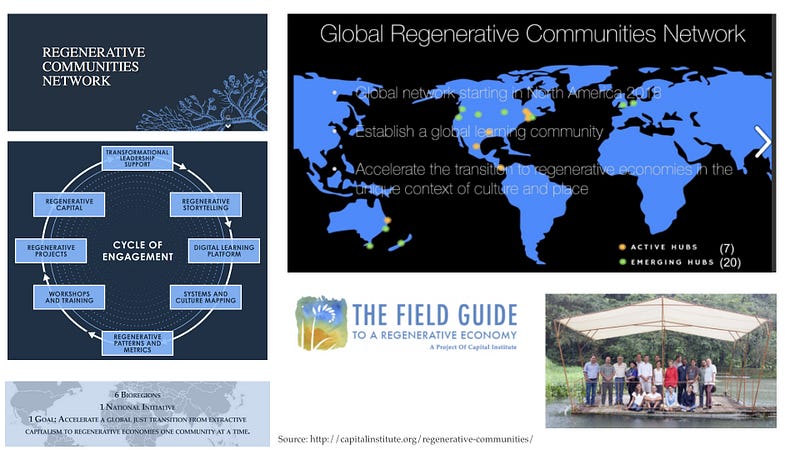

The ‘Regenerative Communities Network’ launched recently by the Capital Institute sets itsself the challenge to region-by-region create regenerative bioregional economies. There are now seven regional Regeneration Hubs of people working at the regional scale to build bioregional biomaterials economies.

Basically we need to shift out of fossil carbon. Our entire material economy is fossil fuel dependent. We need to create a new type of material culture that is biomaterials based and sequesters carbon into everything we use.

There is also an organization called Regeneration Interational that links farmers from around the world who practice regenerative agriculture. The map in the image below shows some examples of where these activities are taking place.

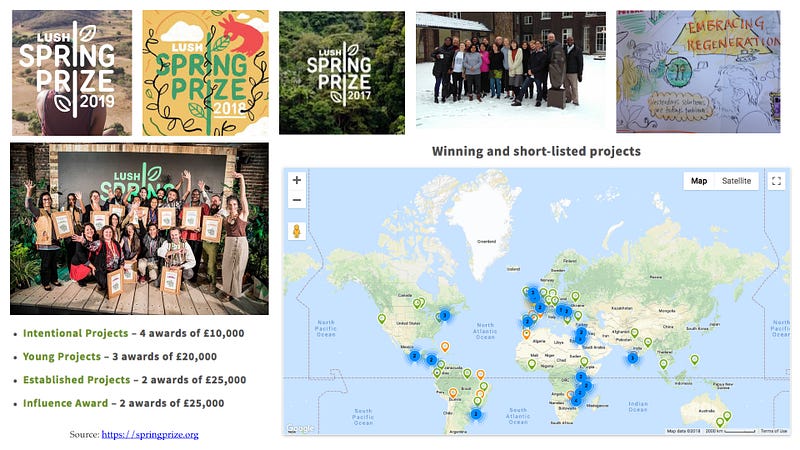

Lush — the ethical cosmetics company — runs the Spring Prize that I have the honour to be on the jury of. Every February we meet to deliberate on how to give away 200,000GBP to organizations that working on social and ecological regeneration.

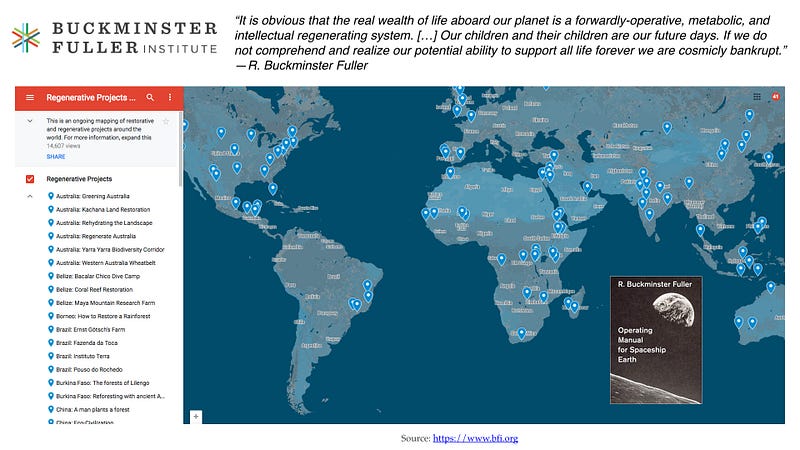

There is some hope. There is a silver-lining to the dark storm clouds we are facing. If you really want to stop watching the bad news have a look at the website of the Buckminster Fuller Institute. My friend David McConville created a google map on which each point you can click on pops up a little video of a story happening in that place of people already doing regeneration work on the ground.

Next year [technically late this year in late December] is the 50th anniversary of ‘Earth Rise’ — the first image from outer space of Earth rising above the moon — and it is also the 50th anniversary of Buckminster Fullers book ‘Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth’. I think we are getting closer to knowing what we need to do and we are beginning to do it.

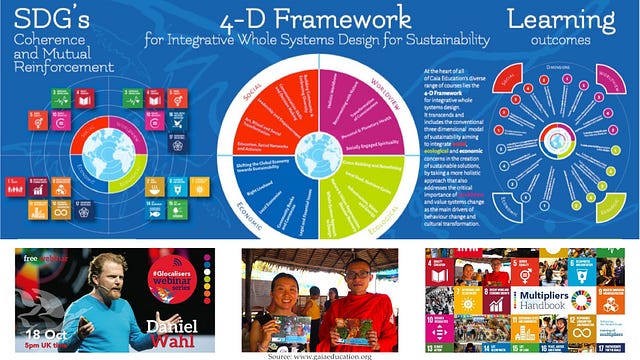

In terms of education and capacity building I have already mentioned Regenesis Group.

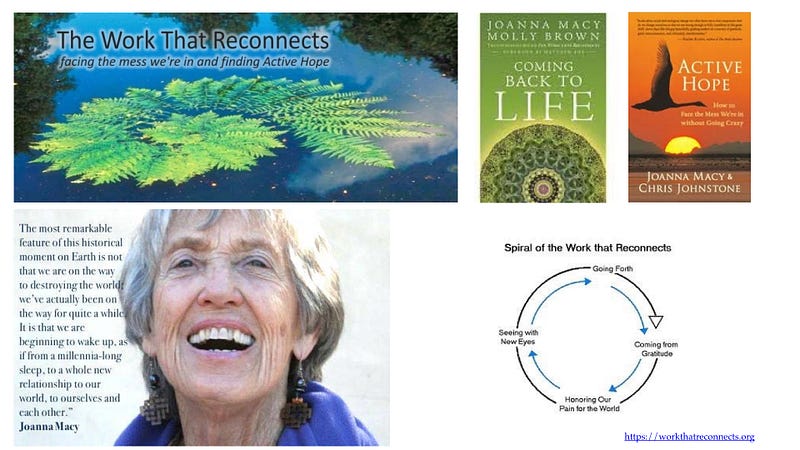

So just to close. This is a great teacher [of mine] — Joanna Macy — who for years has emphasized that the key things we need to change are upstream. The key things that we need to change start in the human heart and in the human relationship with the Earth.

I love what she says here [below]. We have been on the path of destroying this planet for many, many years, probably about 5000 years, since the beginnings of agriculture [which started 8 to 10k years ago but began spreading widely around 5k years ago]. But, there is something special happening right now, we are beginning to redefine our relationships to each other, to this planet, and our potential role of healing this planet.

I am going to close with a poem that Joanna Macy translated by one of my favourite poets, called Rainer Maria Rilke, and it speaks to our time:

Dear Darkening Ground, you have endured so patiently the walls we have built.

Maybe you will give the cities one more hour; Cloisters and churches two;

and those who labour, maybe you let their work grip them for another five hours of seven;

Until you become forest again, and water and widening wilderness, in that hour of inexplicable terror when you take back your name from all things.

Give me just a little more time, give me — just — a little more time,

So I may love the things until they are real, and ripe, and worthy of you.

So I invite you all to love life. Love the opportunity of being alive. We don’t know whether we are going to make this. We are undergoing a species-level rite of passage right now. Rights of passage require that you are not allowed to know for sure whether you are going to make it, otherwise they don’t work.

We are facing a knife’s edge, between a future that is abundant of collaboration with [more than human] nature, or decades of decline and unspeakable, unthinkable situations that we want to avoid. The way to start navigating the path towards the positive is to be in love with life and each other every day a little bit more.

Thank you!

[If you want to watch the whole talk, it is 26 minutes long, links below!]

I uploaded a copy of this talk in my Facebook page in November 1st and by November 7th it had gained more than 14k views. Please help spread the link to the Youtube video to people you know who care.

Regeneration Rising!

(1) [thanks to Christopher Chase for a conversation that helped me see that]

(2) [Thanks to Kevin Barron, used part of this phrase in a comment on social media]

(3) [See also Sean Kelly’s excellent book ‘Coming Home: Birth & Transformation in the Planetary Era’]