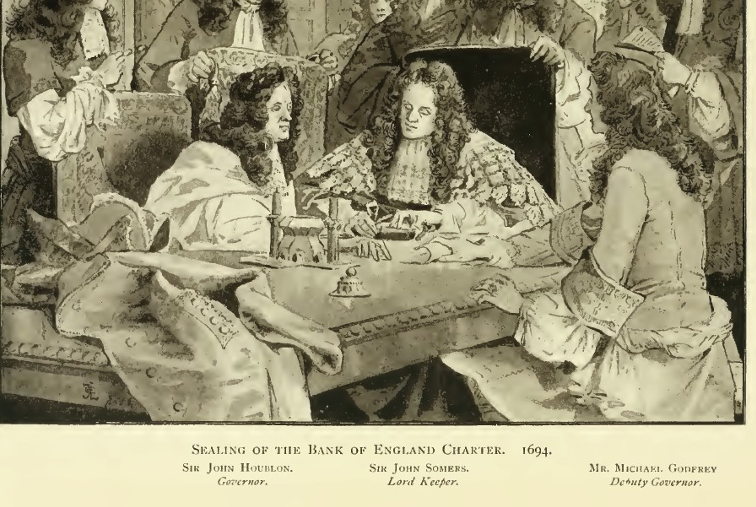

If such an implausible appointment were ever to be made by a Labour chancellor, I would regard it as a great honour. The Bank of England stands at the pinnacle of Britain’s monetary system, which I regard as one of Britain’s great public goods. It is as vital to our economic health as the sanitation system is to public health. The development of the monetary system and the founding of the Bank of England in 1694 represented – despite all its flaws – a great civilisational advance. As the £1,000 billion bailout of the banking sector in 2007-9 proved, thanks to our monetary system, there need never be a shortage of money. We need never lack the money for all that society regards as vital to economic, social, political and ecological stability. I write that with feeling, having worked in countries that lack a developed monetary system, and therefore have no money.

The Bank of England, explained the governor Mark Carney recently, is ‘the only game in town’. The bank’s power – or at least the power of its civil servants and monetary policy committee members – was greatly enhanced during the Blair government. Under Gordon Brown’s watch one of the most important economic tools available to any government – the power to determine the rate of interest (bank rate) – was delegated to a committee of unelected men (and the occasional woman) at the Bank of England. Brown made clear in 1997 that the monetary policy committee was expected to wield this great power independently of parliament’s scrutiny.

David Cameron, as prime minister, and George Osborne, his chancellor, went further when they declared their government was made up of ‘monetary radicals and fiscal conservatives’. They expected unaccountable civil servants at the bank to be dominant in economic policy-making while government ministers at the Treasury sat on their hands. After the most catastrophic financial crisis in recent history, elected government ministers effectively refused to deploy fiscal policy to revive investment, employment and incomes in Britain. Instead they encouraged the bank’s staff to use monetary policy to bail out the private financial system.

By savagely cutting government and local government spending during a period of economic weakness, and at times a slump, while simultaneously encouraging the bank to bail out those that had caused the crisis, the Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition effectively slashed the nation’s income while simultaneously raising its public debt. That is why Britain’s public debt rose to nearly 90 per cent of GDP by 2018 and real wages went into decline – and are still lower than before the crisis.

What powers does the bank have?

Just like every high street commercial bank, the Bank of England has the power to create liquidity out of thin air. That is how it was possible to provide £1,000 billion to the finance sector almost overnight, as the 2007-9 financial crisis deepened. And – just like every commercial bank – it is powerless without borrowers, and in particular without borrowers that hold collateral the bank deems to be of value.

Because the bank operates at the macroeconomic level of the economy, its clients are institutions that have a macroeconomic impact. These include the government and other central banks, as well as commercial banks and other financial services firms. Commercial banks, by contrast, operate at the microeconomic level, providing finance to individuals and firms.

Second, the Bank of England, by way of the Mint, is the only institution that can issue the nation’s currency, sterling, and coins. All other notes and coins are deemed counterfeit. As banks now increase their profiteering by ‘nudging’ consumers into cashless payments, however, this power is declining in importance.

Third, the bank has limited power to maintain and stabilise the value of the currency. It derives this power largely from the health of the economy and because it is backed by 30 million British taxpayers. Thanks to the free market dogma that transformed the bank at the end of the Bretton Woods era, it has only one instrument at its disposal for adjusting the value of the currency: the rate of interest. This means that when speculators attack, as happens periodically, the bank’s only defence is to raise interest rates. High interest rates favour finance capital and rentiers, while low rates of interest favour industry and labour. This means that to defend the currency, the bank has to damage firms and individuals active in the domestic economy. Prior to the deregulation of the 1960s and 70s, the bank had the power to manage and stabilise the currency by intervention in foreign exchange markets rather than by manipulation of the interest rate. Speculators used monetarism’s ‘free market’ economic theory to remove that power and restore the currency to its role as a speculative asset for the rentier class.

Fourth, the Bank of England has ‘supervisory’ powers over banks, building societies, credit unions, major investment firms and insurers.

Finally, the bank has either been stripped of powers, or has declined to use them. The most important of these is the power to influence interest rates across the spectrum of lending. In other words, while a committee at the bank can determine the bank rate (available only to bankers), the bank has given away its power to influence lending rates deployed daily in the real economy. These include lending rates on short or long-term loans, on safe or risky loans, or in real terms, relative to inflation. All are now determined by private bankers operating in the market, and all are much higher than the bank rate. These high rates have deterred investment and are a major reason for the decline of British industry.

The bank has also been denied the power to manage flows of capital across British borders. While it has deployed some limited ‘macro-prudential tools’ to, for example, inhibit flows of money into London property, these are strictly limited. Capital mobility makes it impossible for the central bank to manage rates of interest on all lending and leaves the determination of the exchange rate to the whim of speculators and others working in global capital markets.

Commercial banks are increasingly managing the private payments system – and doing so in their own interests: to cut costs and increase profits. As Frances Coppola argues, ‘a crucial public service has become deeply embedded in a system which is by nature risky.’ In the past, bankers handled payments for firms and for those with bank accounts but most transactions between ordinary people were in cash. No more. Today almost all money is digitised.

A cashless society, as Brett Scott argues, ‘brings dangers. People without bank accounts will find themselves further marginalised, disenfranchised from the cash infrastructure that previously supported them. There are also poorly understood psychological implications about cash encouraging self-control while paying by card or a mobile phone can encourage spending. And a cashless society has major surveillance implications.’

As governor, I would advocate the return of this ‘crucial public service’ and these powers to the Bank of England.

What would you do with the powers the bank has?

First and foremost, I would publicly acknowledge that the private, globalised financial sector is deeply entwined with, and dependent on, our public, taxpayer-backed monetary system and nationalised Bank of England. Some call this relationship parasitic. The financial crisis proved that it is far from mutually beneficial. I would want to ensure that British voters understand that we, as taxpayers, play an important role in support of the private finance sector. What, I would ask, do taxpayers get in exchange for the finance sector’s use of this great public good?

As taxpayers we guarantee deposits in private banks operating in Britain up to £75,000. No other private enterprise enjoys such generous taxpayer-backed guarantees against losses. As a result, banks take even bigger risks than before the crisis, knowing they are now too big to fail. As governor, I would rein in their speculative activities.

The Bank of England manages and maintains the value of the currency central to the speculative activities of the finance sector. But that in turn depends on a sound tax collection system – and on 30 million British taxpayers. The fact that many corporations that trade in Britain rely on our stable currency but do not pay taxes here is often conveniently ignored.

The liberalised, de-regulated global financial system depends heavily on one particular government asset or collateral for its functioning, stability and security. That asset is government debt, which takes the form of publicly-issued bonds or gilts. Global corporations and asset management funds hold large volumes of cash (think of Apple’s vast profits) but their cash mountains are too big to be safely deposited in traditional banks. And in any case, cash does not yield additional gains.

So banks and other big corporations prefer to convert cash into bonds that earn interest over time. The safest bonds are US and UK government bonds. And safe assets like government bonds can be used as collateral to leverage additional finance – just as households would use the value of their asset, a property, to leverage a bigger mortgage. Without the production and circulation of these safe assets, the ‘plumbing’ of the global financial system would quickly become clogged and blocked. Ironically, thanks largely to deflationary policies defined as ‘austerity’ and promoted by orthodox economists and right-wing politicians, there is now a shortage of this safe government collateral/asset.As we know from the experience of quantitative easing, globalised finance relies heavily on taxpayer-backed central banks for liquidity and low rates of borrowing. Citizens cannot borrow at 0.5 per cent from the Bank of England, but the globalised finance sector can. Citizens cannot exchange assets for cash or liquidity with the Bank of England, but globalised banks can.

Worst of all in terms of accountability is the taxpayer-backed ownership of what was once one of the biggest banks in the world: the Royal Bank of Scotland. We, the taxpayers, paid a hefty £46 billion for that privilege, while at the same time guaranteeing £202 billion under the asset protection scheme. The government’s sale of 7.7 per cent of RBS stock in June 2018 was undertaken at a loss of £2.1 billion.

Given this dependence of the private finance sector on the public good that is the monetary system, I would ensure much greater accountability to parliament for the bank’s activities. Before making decisions on, for example, the bank rate, I would insist that the bank draw on a much wider range of experience and expertise within the productive sector of the economy.

Second, I would invite debate about the bank’s mandate and encourage parliament to widen it. Currently it is ‘to maintain monetary and financial stability’, which effectively means targeting inflation. The obsession with inflation derives from the influence of creditors within the finance sector. Inflation erodes the value of their assets (debt), whereas deflation or noflation increases the value of their assets.

While fully aware of the dangers of inflation, I disagree that it should be the sole target, and would suggest that parliament consider making full employment a target. I would welcome John McDonnell MP’s proposal that the bank should target an increase in productive lending by commercial banks and financial institutions, as opposed to speculative lending on, for example, London property. To do this, the bank should return to its role of offering guidance to bankers in their lending – and penalise those that engage in speculative lending.

What else would need to change?

This would only work if it were part of a sustained attempt by a democratically-elected government to once again regain public authority over the privatised monetary system, to ensure that it works for all, not just financial interests. The Bank of England and the British monetary system have advanced since 1694, but not without periodic conflicts between society and the finance sector – with the latter determined to subordinate the monetary system to private interests. At regular intervals society wrenches back control. The last time finance served the economy rather than mastering it was from 1945 to the 1960s.

Reclaiming the monetary system will require society to once again challenge the enormous power now wielded by private capital markets, not just over the Bank of England and the British economy but over the global economy. It will require greater public understanding and defence of the monetary system. It will also require international cooperation with like-minded citizens and politicians in the US, Europe, Latin America, Asia and Africa.

Above all, it will require political will. We must understand that the monetary system was not privatised by financiers and speculators. It was privatised by democratically-elected politicians. For my appointment to be effective in transforming the system, ethical politicians must reverse the laws and regulations that permitted the private takeover of the great public good that is our monetary system.