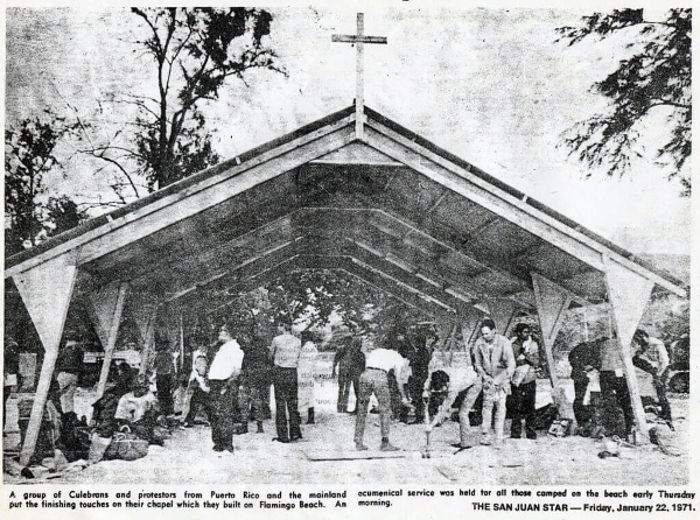

Original caption: A group of Culebrans and protestors from Puerto Rico and the mainland put the finishing touches on their chapel which they built on Flamingo Beach. An ecumenical service was held for all those camped on the beach early Thursday morning. (The San Juan Star, Friday January 22, 1971)

The building of the church met its objective. In January 1971 the U.S. Navy ceased its bombing of Flamenco Beach on the Puerto Rican island of Culebra.

Bob Swann had traveled to the island with a small group of peace activists at the invitation of the islanders who were distressed that their beach, named one of the ten most beautiful in the world, was being used as target practice. There had been a church at Flamenco before the bombing. The Americans decided to build a new church in its place as part of the demonstration. Because Bob was a carpenter, he was recruited to create a design and oversee its construction.

It was not one of the tall, thin, and graceful churches that you see in New England villages. There were no convenient building supply stores on the island. Lumber had to be pre-ordered, then ferried in from the big island, then precut in town where there was electricity, and then hauled out on trucks to Flamenco for assembly by many hands. Salt water helped to set the cement pilings.

What emerged was a typically Bob Swann design, a wide wooden structure with low slung roof made of plywood, and a two-by-four cross at its peak. It was a perfect open-air pavilion for picnics at the beach and it would do for a church as well.

The San Juan Star featured a picture of the completed church on its front page. The protest numbers swelled as a result, accompanied by singing, eating, and lots of old fashioned partying. The Navy stopped its bombing and Flamenco Beach was returned to the control of island’s local government.

The pavilion finally blew down in 1989 during Hurricane Hugo, but the mile-long beach continued to be run as a well-maintained campsite by island authorities. As word spread of its quiet beauty and affordability Flamenco Beach became the vacation destination for Northeastern organic farmers during the winters. On the road to the beach, islanders began constructing houses again—some probably without permits in what is an informal squatting on land, which is common throughout Puerto Rico.

In 2017 Hurricane Maria hit Culebra hard. Clean up and rebuilding is still ongoing. I was not able to visit this year as I usually do, but I did visit San Juan, the capital of Puerto Rico, where I saw two responses to the devastation after Hurricane Maria.

I read about Caño Martín Peña Community Land Trust (El Fideicomiso de la Tierra del Caño Martín Peña) before leaving for San Juan and connected in advance with Lyvia N. Rodríguez Del Valle who is Directora Ejecutiva of Corporación del Proyecto ENLACE del Caño Martín Peña, the partner organization of the land trust.

She gave me a tour of the Buena Vista Santurce neighborhood on the day of a health fair. It is one of eight neighborhoods in Caño Martín Peña. The land trust holds a total of 200 acres that sit on either side of a canal. At its prime the canal served as a drainage basin for downtown San Juan. Debris has largely filled in the canal; raw sewage flows unchecked into it. ENLACE is leading an effort to clean the canal and restore the tropical estuary.

The 200 acres are also home to what was an “informal” settlement that was built up haphazardly along the canal over five generations. Fifteen hundred families live in the neighborhoods abutting the canal. Not only homes, but businesses, schools, churches, and community buildings were all built to serve the needs of canal residents. But without deeds and proof of ownership, canal residents did not qualify for city services. Street maintenance, water, sewer, and electric services were all neglected. Frequent flooding left the population vulnerable to diseases that were carried in the contaminated water.

It took two decades of organizing residents and lobbying the Puerto Rican government, but finally a special act of the Puerto Rican legislature permitted the forming of a community land trust and a transfer of all 200 acres into the trust. Building owners were given “surface” rights on land trust land, which provided secure tenure. The land trust has further engaged the eight communities in a planning process to appropriately develop remaining land, including resettling those in the most fragile ecological areas.

But, of course, Hurricane Maria took a toll. Blue tarps meant to temporarily serve as roofs are now compromised and leaking. Support from FEMA is slow. The community land trust has joined with other San Juan groups in a project called “tarps to roofs” through Global Giving.

Lyvia Rodriguez reports that they originally estimated the cost of each roof at $8,500—but the shortage of building supplies and shortage of contractors (all busy on other projects) has put the cost per roof at $15,000. A thousand new roofs are needed.

The approach the land trust has taken is to let each of the eight communities know how many roofs they can expect in each round of funding. The communities then set priorities: elderly and handicapped first, and then work down the list. It is a slow process.

El Fideicomiso de la Tierra del Caño Martín Peña is in the heart of San Juan, close to its famous “golden mile” of banks and high-end shops. There is nothing golden about the settlement around the canal except the spirit of its people, and the shining, shy, faces when visitors come by and take notice. The two decades of organizing and the security of tenure provided by the community land trust has given residents an optimism and pride that is tangible even with the extensive clean up still ahead.

While in Puerto Rico I also met with Francisco Susmel, a staff member for Techo, an Argentinian organization that works throughout South America and the Caribbean to build homes after natural disasters. Francisco is an architect overseeing a volunteer crew of workers in San Isidro, an unincorporated “census place” in the municipality of Canovanas—about a 30 minute drive east of San Juan. He works in the informal settlements of Villa Hugo and Valle Hill, known locally as Hugo I and Hugo II. They were so named because following Hurricane Hugo—so named after Hurricane Hugo that hit Puerto Rico in 1989. Following Hurricane Hugo, the Mayor of Canovanas invited the newly homeless to build in those two areas without having to acquire permits.

While in Puerto Rico I also met with Francisco Susmel, a staff member for Techo, an Argentinian organization that works throughout South America and the Caribbean to build homes after natural disasters. Francisco is an architect overseeing a volunteer crew of workers in San Isidro, an unincorporated “census place” in the municipality of Canovanas—about a 30 minute drive east of San Juan. He works in the informal settlements of Villa Hugo and Valle Hill, known locally as Hugo I and Hugo II. They were so named because following Hurricane Hugo—so named after Hurricane Hugo that hit Puerto Rico in 1989. Following Hurricane Hugo, the Mayor of Canovanas invited the newly homeless to build in those two areas without having to acquire permits.

Essentially a wetland, these neighborhoods flood frequently. Because residents do not have proof of ownership of their homes, government agencies do not respond to their requests for services. Nor did FEMA after Hurricane Maria.

Francisco’s approach is to gather residents together at the small store that also serves as a community center. He explains that a volunteer team will help construct pre-designed and pre-fabricated houses. Residents are responsible for preparing their site: clearing debris, leveling the ground, and digging holes for the posts. Each family signs a contract detailing what they can do to help build their own home and promising to help with the next set of homes.

The concept is to train folks in simple construction techniques that will be a long-term resource for the community.

But Hugo I and II do not have the advantage of two decades of community organizing as in Caño Martín Peña. Contracts aren’t always met and the new homeowners complain that the house is not painted, nor the floor finished, nor steps built—all items they committed to do themselves.

Still, homes are built. Volunteers from Southern and Central America have come to help. They stay in the nearby school gymnasium at night, wake up early, leave before the students arrive, and then head to their work sites—despite their lack of training, they are ready to jump in and create safe homes for strangers.

Still, homes are built. Volunteers from Southern and Central America have come to help. They stay in the nearby school gymnasium at night, wake up early, leave before the students arrive, and then head to their work sites—despite their lack of training, they are ready to jump in and create safe homes for strangers.

It is pre-fab construction—just like the church on Culebra. The lines of the roofs might not be as straight as wished. It might take more nails than need be to hold a post. But the energy these volunteers bring ignites the natural good spirit of the neighborhoods. The rebuilding is slow, but steady.

Today is the centenary of Bob Swann‘s birth. In 1967 Bob organized the first community land trust with Slater King, which these many years later provided a solution for the residents of Caño Martín Peña who were living without secure land rights. Bob was also founder of the Schumacher Center in 1980. A tip of the hat to Bob on his 100th birthday. We miss him!

Stephanie Mills’ biography of Bob Swann, On Gandhi’s Path, is available through your local bookstore.