The United States government has now officially embraced climate change as a catastrophe in the making. Only it contends that the catastrophe is now inevitable no matter what humans do…and so, we should do nothing at all since whatever we do won’t matter much.

That, at least, was the justification offered for freezing fuel-efficiency standards for vehicles after 2020. For the National Transportation Safety Board which issued a report containing the justification, the phrase “Every little bit helps” has morphed into “Every little bit won’t matter.”

The problem, of course, is that if this becomes the attitude of everyone trying to mitigate climate change, almost nothing will get done.

But the report does highlight one very important problem for those who desperately want to address climate change: Climate change is no longer a “crisis.” As French thinker Bruno Latour reminds us in his book Facing Gaia, climate change is not really a “crisis,” at least not anymore. A crisis comes and goes. Climate change isn’t going anywhere except toward a place which is much worse. It isn’t going to pass. It is going to endure.

That is the hard part about it. Addressing climate change does not mean taking temporary emergency measures which can be relaxed after the crisis has passed. Addressing climate change means making profound and permanent changes in the way we live. That is, of course, why doing much of anything is opposed vehemently by interests dependent on fossil fuels for their livelihoods such as the auto industry and, of course, the oil industry. There’s no going back to the way things were after the crisis passes because it’s not going to pass.

Latour styles climate change as the third world war of the 20th century, one that most of those who lived through it didn’t even notice. We didn’t even notice that the climate was waging a successful campaign destined to make much of the Earth uninhabitable for humans and untenable for modern civilization. That was the moment of crisis if there ever was one in this fight. That we could have won that war if we as a global society had noticed it was happening is now lost on most. With multiple tipping points probably already passed, we are now left with “a profound mutation in our relation to the world,” he writes.

Our response is manifold. Some choose despair. Some choose denial. Some suggest that we double down with additional modern attempts to dominate nature through something called geoengineering. According to those advocating this approach, the problem is not that we have assaulted the planet and its climate; it’s that we have not dominated their workings enough!

We are told we face crises in education, in leadership, in morals, and in politics. We have health crises and food crises and toxic chemical crises. The soil, the water, the forests and the fisheries are all in crisis. It never occurs to the bulk of the population nor to its leadership that these crises are all related to systemic changes in the landscape, the sea and the atmosphere linked to our profligate use of energy and resources.

Because half measures do not seem enough in the face of this great ecological storm of change, the U.S. government now says that no measures at all need to be taken. This is not the voice of despair. Nor is it the voice of denial in the brute sense of the word. This is the voice of a child who simply does not want to change even though he or she now understands that change must come.

Yet children most often adapt and that’s how they grow up and mature. But great masses of people can remain dangerously immature. Swiss psychologist Carl Jung wrote that the reason that collective guilt is so lightly worn—he was referring the Germans in World War II—is that when, say, 70 million share the guilt, they only seem to feel one seventy-millionth of it.

This is part of the collective drama we live in. Some feel the results of our ultimately ruinous way of life first. And, some feel it more brutally because they haven’t the means to shield themselves. While the rest may feel some sense of blame, this does not weigh heavily enough to slow down their daily lives, not yet, at least.

But slowing down is really the first step. The availability of cheap and growing energy supplies in the industrial age has beckoned us to go faster and faster and never slower. And yet, slowing down is a first step in noticing. And, noticing is a next step toward understanding. After that comes imagining how we might live in ways that mitigate the onrushing catastrophe of climate change and resource depletion. That’s what the mature mind does in the face of unalterable change.

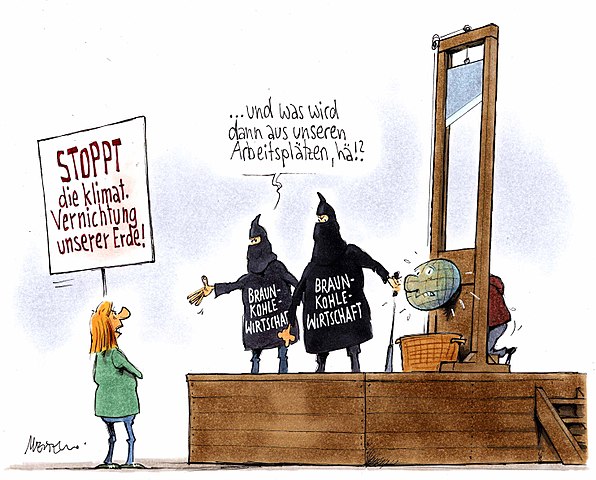

Image: Caricature by Gerhard Mester on climate change and coal burning: Jobs argument (2015). Translation:

Protestor: “Stop the climate destruction of our earth!”

Brown Coal Economy (hooded figures): “And what will become of our jobs, huh?”

Via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:20150715_xl_145658-o13592-Karikatur–Gerhard-Mester–Klimawandel-und-Kohleverbrennung–Totschlagargument-Arbeitsplaetze.jpg