“It’s like watching a state circle the drain.”

That’s what journalist Corie Brown said about Kansas on a recent Strong Towns podcast. This April, Brown wrote a piece for New Food Economy about her 1,800-mile drive through the state. She discussed the state’s emptying out, noting firsthand the struggles of rural towns and the farms surrounding them.

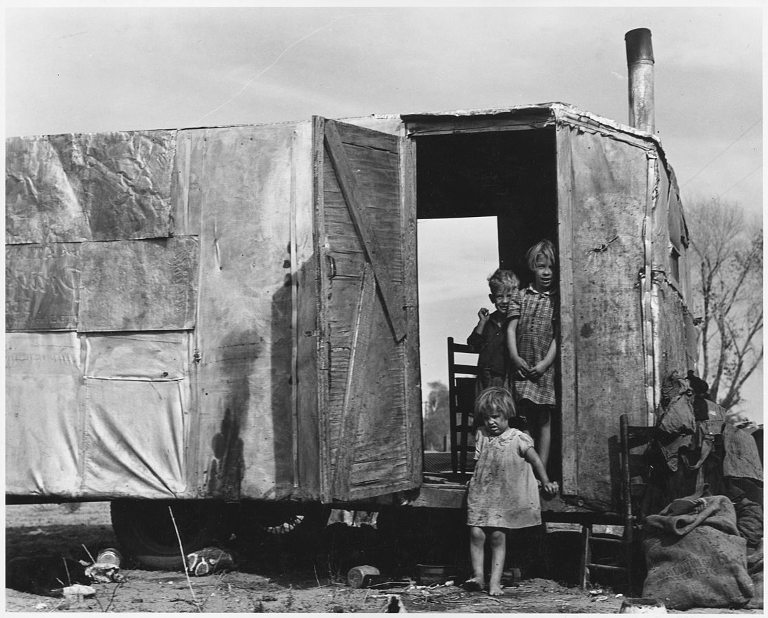

“That’s the thing about rural Kansas: No one lives there, not anymore,” she wrote. “The small towns that epitomize America’s heartland are cut off from the rest of the world by miles and miles of grain, casualties of a vast commodity agriculture system that has less and less use for living, breathing farmers.”

The Midwest has always been a land of commodities—crops like corn, soybeans, and grain. Kansas is a grain-producing state: two years ago, it grew 467 million bushels of grain across 8.2 million acres. But as farmers compete in a global market that is overflowing with grain, they are struggling to survive—even though, as Brown noted during her interview, “they’ve never worked harder, they’ve never worked longer hours.”

Meanwhile, a recent article in The Atlantic highlighted the “zombie small businesses” amongst chicken farmers across the United States, many of which are contractors to large agribusinesses like Tyson and Purdue. “The big company provides the chicks,” reporter Annie Lowrey writes. “The contract farmer raises them into chickens. The big company slaughters them for meat. It packages and brands that meat under one of dozens of labels. And it sells it cheap to the American consumer.”

So what’s the big deal, you ask? Lowrey continues:

The issue, the Small Business Administration report found, is the level of control that the integrated poultry company exerts over the farmer. These big operations do not act like department stores, choosing goods from a broad variety of vendors and fostering competition and innovation. They instead act like a lord with serfs, or a landowner with sharecroppers. …[F]armers have complained about and litigated against such contractual relationships for years. “The company has 99-and-a-half percent control over the grower,” said Jonathan Buttram, the president of the Alabama Contract Poultry Growers Association and an outspoken critic of the industry. “I’ll list what they tell you: what time to pick up the chickens, what time to run the feed, what time to turn the lights off and on, every move that you make. Then, they say we’re not an employee—we are employees, but they won’t let us have any kind of benefits or insurance.”

Yet for all the control the poultry businesses have over the farmers, the farmers maintain significant financial and legal risk. They have little job security. They can get dumped for a different supplier, and face a tournament-style system that pits them against fellow growers. They are responsible for financing their own operations, and face the persistent threat of foreclosure.

These stories are important, because they highlight the debilitating “bigness” of our agricultural market—along with the desperation and emptiness that bigness often creates. These farmers feel trapped in a system of growing and harvesting that is killing their land, animals, and way of life. Yet changing the way they farm, or the trajectory of their towns, seems impossible. The margin for error is far too small, the potential cost far too big.

Industrialized agriculture prioritizes efficiency and quantity over human and ecological flourishing: it pushes farmers to plant more commodities over greater swaths of land, or to cram even more chickens into putrid and disease-ridden chicken houses, despite the animals’ suffering and discomfort. This is the only way to turn a profit. Yet when farms industrialize, it does not just impact them—the towns around them also suffer. The economy has no “local orientation,” as Brown puts it.

For quite some time, the nation’s heartland has been struggling with a “brain drain”—a slow exodus of youthful talent and energy—alongside a slow collapse of small-town economic life. In his book The Omnivore’s Dilemma, Michael Pollan documents the way tractors and chemicals have replaced farmers and farmhands, slowly eating away at the jobs that once gave life to these small communities.

This agricultural economy has put an enormous burden on the surviving farmers: despite their long hours and arduous labor, they are completely reliant on the erratic boom and bust of the market. The name of the game is to farm more land with fewer people and more technology, chemicals, and equipment. Today’s farmers are desperately trying to increase their yields and get more land, in exchange for ever-shrinking profits.

“There’s literally no way for you to benefit from doing a better job,” Brown says on the podcast. “It’s such a no-win game for American farmers, it’s hard to imagine they still play it—but they play it, and they play it hard.”

American agriculture has been playing the globalized commodity game for a couple centuries now, and although we never seem to win it, we can’t seem to quit it either. Patterns shift and times change, yet we still plant from fence row to fence row, telling farmers to “get big or get out.”

Today’s farmers—be they grain farmers or chicken farmers—are not all that different from those John Steinbeck wrote about in his classic work, The Grapes of Wrath: they are still trapped within a system of production that little prizes them and their land. At the beginning of his book, Steinbeck shares a conversation between the tenant farmers and the “owner men,” who have driven them to plant cotton without diversifying:

…[A]t last the owner men came to the point. The tenant system won’t work any more. One man on a tractor can take the place of twelve or fourteen families. Pay him a wage and take all the crop. We have to do it. We don’t like to do it. But the monster’s sick. Something’s happened to the monster.

But you’ll kill the land with cotton.

We know. We’ve got to take cotton quick before the land dies. Then we’ll sell the land. Lots of families in the East would like to own a piece of land.

The tenant men looked up alarmed. But what’ll happen to us? How’ll we eat?

You’ll have to get off the land. The plows’ll go through the dooryard. …It’s not us, it’s the bank. A bank isn’t like a man. Or an owner with fifty thousand acres, he isn’t like a man either. That’s the monster.

In California, Steinbeck writes, “The little farmers watch debt creep up on them like the tide. They sprayed the trees and sold no crop, they pruned and grafted and could not pick the crop. …The little orchard will be a part of a great holding next year, for the debt will have choked the owner. This vineyard will belong to the bank. Only the great owners can survive….”

In today’s agricultural economy, only the great owners survive. Across the nation, 10 percent of farms are responsible for 87 percent of food production. The little farms and towns and economies that once thrived around them die out, their life and vibrancy bleeding into other lands. The Grapes of Wrath and its vision of scarcity and enslavement to big agribusiness isn’t just our past—it is also our present. And it will be our future, if we can’t turn things around.

Adjusted for inflation, today’s dairy operators fetch 38 percent less than they did in 1980. Yet dairy herds have grown by 124 percent, while operators have fostered improvements in milking technology, nutrition, and hormone regimens in order to bolster their output. Despite this, America has lost half its dairy farmers in the past 16 years.

Our growing agricultural reliance on commodities, meanwhile, has narrowed both the power and variety of the corn industry: two companies, DuPont (Pioneer) and Monsanto, control 58 percent of the U.S. market for corn seed. Three (Archer Daniels Midland, Bunge, and Cargill) control 90 percent of the global grain trade. Four (Archer Daniels Midland, Cargill, Staley Manufacturing Co., and CPC International) control 85 percent of the high fructose corn syrup industry.

“The monster’s sick. Something’s happened to the monster,” Steinbeck writes in The Grapes of Wrath. We’re seeing the same sickness plague our country today—a monstrosity that curbs the growth and health of small farmers and instead makes big farmers bigger.

Bigness can kill both farms and farmers alike—no one is safe in today’s economy. Last year, a study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that agricultural operators are more likely to commit suicide than workers in any other occupation. The suicide death rate for farmers is more than double that of military veterans, according to Newsweek.

Wendell Berry—son of a Kentucky farmer, writer of novels and poems, and environmental activist—has long argued against our industrialized agriculture. He believes farming should not be seen solely as a commodity game meant to serve a global audience. Tied as it is to land and place, animal and plant, he views farming as inherently local.

As Berry once wrote for Orion Magazine:

It has become increasingly clear that the way we farm affects the local community, and that the economy of the local community affects the way we farm; that the way we farm affects the health and integrity of the local ecosystem, and that the farm is intricately dependent, even economically, upon the health of the local ecosystem. We can no longer pretend that agriculture is a sort of economic machine with interchangeable parts, the same everywhere…. We are not farming in a specialist capsule or a professionalist department; we are farming in the world, in a webwork of dependences and influences probably more intricate than we will ever understand.

Writers like Berry, Steinbeck, Gene Logsdon, and John Crowe Ransom (among others) have all warned of this process’s consequences. They envision a future for farming that cultivates vibrant local towns and stanches the flow of youth, money, and food from rural communities. They identify the deep importance of agricultural flourishing—not just for the towns that lose them, but for our entire economy and culture.

We need to start listening to them. An empty heartland, after all, cannot sustain the body of the nation.