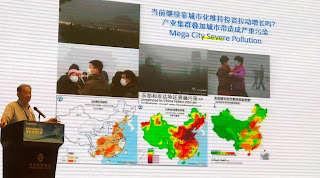

I have never been terribly fond of cities, but if you had to live in a Chinese megacity, you could do worse than Chengdu. It is the capital of Sichuan Province so you know the food is going to be good. It has been sobriqueted at one time or another as “The God-favored Land,” “Hibiscus City,” “Brocade City,” “Civilized City,” “Garden City,” “World Gastronomic Capital,” and “Model City for Environmental Protection,” whose biggest sightseer draws are the wild herds of pandas. It is also home to 16 million permanent residents, has 20 districts (former cities and towns it swallowed up somewhere along the millennia), is said by Forbes to be the fastest growing city on Earth, and is expected to remain on that blistering pace for at least the next decade. Apart from the pandas, those are not pluses.

Chengdu shared bikes are activated by the WeChat phone app.

Chengdu shared bikes are activated by the WeChat phone app.

The site and name have remained unchanged since at least the time Chengdu became the capital for the 9th Kaiming King of the Shu 2300 years ago. As recently as 2100 years ago it had its first school, called Shishi (“thank you”) built by Governor Wen Weng. According to legend, around the end of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220), Zhang Daoling, later known as Celestial Master Zhang Tianshi, cultivated and preached the way of the Tao on Mt. Qingcheng, now revered as the birthplace of Taoism.

I am here at the invitation of Mr. Wang Li, Deputy Director of the UNESCO Rural Development Center, to speak of ecovillages in the context of environmental education to the 9th annual meeting of the Dujiangyan International Forum. The theme of this year’s forum is “Harmonizing Urban-rural Education Development in the Context of Education 2030.” I honestly expected most of the speeches to be real snoozers (not a heavy lift after 20+ hours of air travel), given titles like “Let Education Be Implanted with the Green Heart and Share the Beautiful Earth,” but I was in for a real surprise. The first talk, by the deputy director of an academic committee of some Chinese university, had me hanging on every word.

To be fair, Wen Tiejun had every right to be outspoken. As a teenager at the time of the Cultural Revolution he was yanked from school and sent out to a gruesome life of menial labor on a remote collective farm, along with his parents, who were being punished for being intellectuals. Later in life he won a favored party position and as a policy developer gained a mastery of Maoist language and framing. This was how his 30-minute opening keynote at the forum could be so devastating.

To be fair, Wen Tiejun had every right to be outspoken. As a teenager at the time of the Cultural Revolution he was yanked from school and sent out to a gruesome life of menial labor on a remote collective farm, along with his parents, who were being punished for being intellectuals. Later in life he won a favored party position and as a policy developer gained a mastery of Maoist language and framing. This was how his 30-minute opening keynote at the forum could be so devastating.

Bear in mind that this is an event far into the interior of China, co-sponsored by a UN Agency and the Chinese government. I almost could not believe what I was hearing. I had to start scribbling notes.

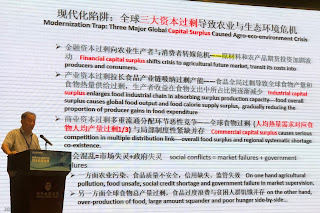

One of the themes of this forum is equalizing the educational opportunities of rural and urban regions. Many of the presenters prepared talks on bringing rural students into the digital age, or using cyber enhancements to improve pedagogy. Wen called that moving from a colonial knowledge system to a neocolonial exploitive system. It is the old paradigm of “development-ism,” he said: “colonization, overproduction, overconsumption, capitalization of the economy.” Developed countries were going all over the world and paying vast sums in “foreign aid” to “propagate the crisis.” It was the same mentality that brought about World War II, he said. First you build massive arsenals so you can build massive industrial infrastructure, then you have to use it, destroy it, and build newer and bigger replacements.

“We need a decolonial policy,” he demanded, taking indirect aim at Li Xaoping’s Belt and Road initiative. He told the assembly that if you want rural revitalization you need to put the culture back into agriculture. You need ecological agriculture, farmer rights, and a bottom-up love for environmental sustainability.

The former author of Maoist slogans ticked off the list of recent Chinese government slogans:

The former author of Maoist slogans ticked off the list of recent Chinese government slogans:

- Integrate Urban and Rural (2002)

- Scientific Development (2004)

- A Harmony Society (2004)

- Multifunction Agriculture (2006)

- Eco-Civilization (2007)

- Inclusive Growth (2009)

If you want to put meaning into meaningless slogans, he said, think about an eco-civilization that means local resource sovereignty, multidiversity solidarity, and sustainable ecological safety. What China was doing instead, he complained, was adopting an Anglo-American model of very destructive neocolonialism. It destroys the fabric of culture, soils and health. “Modernization is a trap.”

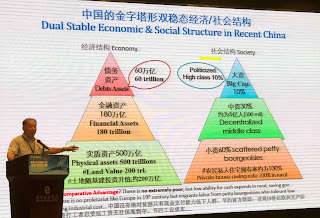

Giving an example, he said the East Asian Land Reform initiative went from ideals of Confucius (good governance arises from good-hearted people) and community stability to the largest percentage of the population becoming petty bourgeois and omni-destructive consumerists. What was cast as land reform ended up destabilizing Asia—most dramatically India—separating rich and poor, pushing a third of the population into landless, jobless poverty, threatening two thirds of the states with growing insurrections, and making 90 percent of those who counted themselves employed no more than slaves of an unstable grey economy, all the while accelerating pollution, land degradation and climate change.

Giving an example, he said the East Asian Land Reform initiative went from ideals of Confucius (good governance arises from good-hearted people) and community stability to the largest percentage of the population becoming petty bourgeois and omni-destructive consumerists. What was cast as land reform ended up destabilizing Asia—most dramatically India—separating rich and poor, pushing a third of the population into landless, jobless poverty, threatening two thirds of the states with growing insurrections, and making 90 percent of those who counted themselves employed no more than slaves of an unstable grey economy, all the while accelerating pollution, land degradation and climate change.

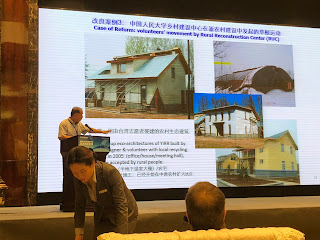

Wen shows strawbale houses being built by volunteers as an example of what rural China needs more of.

I was looking around the room and trying to see if anyone else was as dumbstruck as I was, but they applauded Wen’s candor. This is not your daddy’s China anymore.

In March 2018 China amended its constitution to include the advancement to Eco-civilization as a duty of government at all levels.

UNESCO Office Director of the International Training Center for Rural Education Zhao Yuchi, seated next to me, leaned over and said, “We are the people who are eating the first crabs.”