The following story is the eighth installment in a new series we’re calling “10 Stories of Transition in the US.” Throughout 2018, to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Transition Movement here in the United States, we will explore 10 diverse and resilient Transition projects from all over the country, in the hope that they will inspire you to take similar actions in your local community.

For more information about Transition, please visit www.TransitionUS.org/Transition-101. Click here to view other stories in this series that have already been published, and here to subscribe to the Transition US newsletter if you’d like to be notified of additional stories as they become available.

While more and more people every day are becoming concerned about the impact humans are having on our planet, finding solutions to global problems like climate change, resource depletion, and economic instability can often seem overwhelming. In response to this need for clear and accessible ways to build resilience in the face of uncertainty and mounting social and environmental challenges, Transition Streets is helping to bring neighbors together to build community and take action right where they live. Launched in the US in 2015, this program empowers people all over the country to begin creating a better world now, household by household and block by block.

“Most people are aware of our dwindling natural resources,” says Transition US Co-Director Carolyne Stayton, “and that our current lifestyles are the cause of many of our ills. We are pumping pollutants into the air that exacerbate climate change and result in destructive weather patterns: massive wildfires in California and the West, floods in Houston, and more frequent and forceful hurricanes in Florida. To be part of the solution, we need to know where to begin. Transition Streets offers community members concrete steps for taking action. As Joan Baez famously said: ‘Action is the antidote to despair.'”

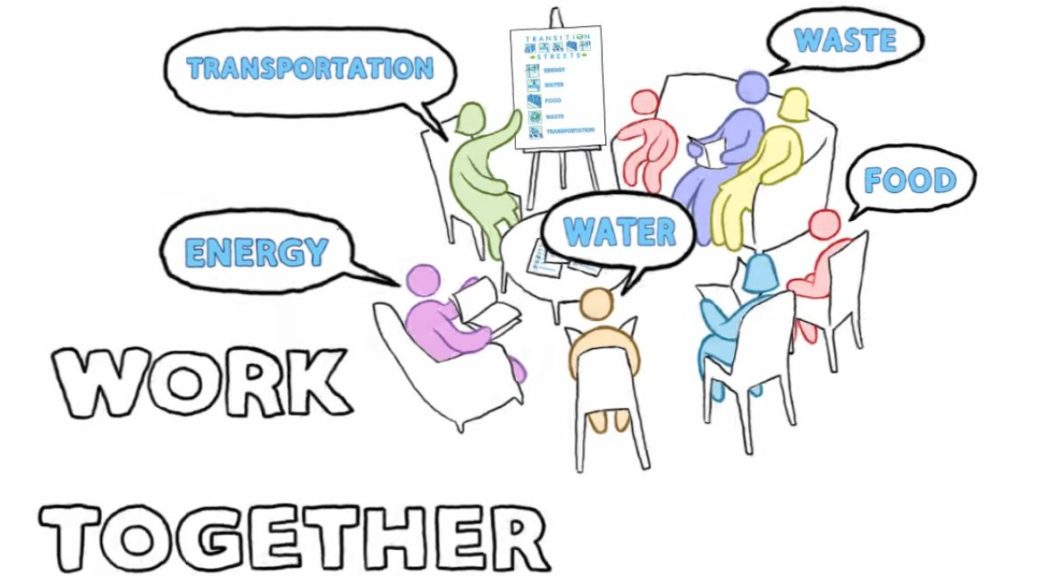

As more and more people come to the realization that our government isn’t likely to address these challenges on their own, a lack of support for those who are committed to taking action can leave many isolated and feeling hopeless about the future. As an antidote to this particular despair, Transition Streets offers a unique opportunity for people to meet with their neighbors, learn more about each other’s interests and skills, and brainstorm together how they can conserve precious natural resources while reducing household expenses. This seven-session program encourages participants to become more aware of their environmental impact and support each other in reducing energy and water use, waste production, and transportation miles, while inspiring new actions that grow local food, reduce carbon emissions, and build community.

As Stayton describes it, “Transition Streets was developed by Transition Town Totnes in the UK, where it was presented with the Ashden Award for Sustainable Energy. It offers a downloadable handbook, as well as facilitation and outreach guides, that provide participants with simple, actionable steps they can explore together.”

In adapting this program, Transition US enlisted a cadre of experts in five main topic areas – Energy, Water, Waste, Transportation, and Food – adding resources relevant to the US and removing those that were not. With 550 households in the UK each saving an average of $900 and shrinking their carbon footprint by 1.3 tons per year, communities in the US were excited to get on board. When the program was first launched, 12 different Transition groups in Albany, CA, Berkeley, CA, Bozeman, MT, Charlottesville/Albemarle, VA, Howard County, MD, Humboldt, CA, Goshen, IN, Manitou Springs, CO, Milwaukee, WI, Missoula, MT, Newburyport, MA, and San Diego, CA all signed-up to start their own groups.

By working collaboratively, Stayton explains, participants receive the added benefits of “friendly peer-pressure from their near neighbors to hold each other accountable, support from each other in making changes, and even stepping out further to undertake additional activities together.”

“The real juice happens in the sharing part,” says Linda Currie, who co-founded Transition Berkeley in 2011. “People liked hearing what others were doing.”

Some of the initiatives that participants have embraced so far are riding bikes instead of driving cars, lowering the thermostat in summer and raising it in winter, investing in power-saving surge protectors, reducing time in the shower, and generating less waste. When participants start to feel the impact of taking these small steps, they feel empowered to take even bigger, collective actions.

Many communities have found innovative ways to use Transition Streets to address their own unique needs. For instance, Transition Fort Collins designed a Green Renters program to serve the nearly 50% of their local population that rents instead of owns, resulting in a new class at Colorado State University. Transition Albany used the program to develop the Albany Sustainability Committee, working to help residents implement their city’s Climate Action Plan. Currently, a water-saving edition of Transition Streets is being created for drought-prone areas in California, and a related curriculum on emergency preparedness will also soon be available.

Currie describes how she has always, “loved the transformation that happens when people come together in small groups with a shared intention. We each have so much power to inspire each other just by sharing from our experience. I love seeing the light bulbs that go off for people when they realize what is possible.”

While the main focus of Transition Streets is to inspire people to take a more active role in addressing environmental issues, increased social cohesion is an important byproduct of the program.

While the main focus of Transition Streets is to inspire people to take a more active role in addressing environmental issues, increased social cohesion is an important byproduct of the program.

“What we had imagined, but greatly exceeded,” explains Stayton, “was the element of community-building that Transition Streets provides. Participants were grateful for the well-designed handbook and suggested action steps, but they were even more enthused about getting to know their neighbors. They enjoyed going into each other’s homes (often for the first time), learning about each other’s lives, and finding out what other interests their neighbors pursued. Transition Streets gave participants a new means to realize the kind of community that many of us long for, that of a familiar and friendly neighborhood.”

Living in the San Francisco Bay area, one of the challenges for Currie was letting her neighbors know about the Transition Streets program and getting a group to commit to meeting seven times to go through the program together. Other communities have used a variety of different approaches to get people involved in the initiative. In San Diego, California, an organizer found participants through the neighborhood listserve Nextdoor. In Charlottesville, Virginia, they partnered with city government to raise awareness. In Missoula, Montana, the group found each other through a local church.

By openly speaking about the challenges neighbors face and the solutions they envision, Transition Streets participants come to realize the wealth of knowledge, skills, tools, and potential they have in their community. Drawing on group wisdom and energized by a heightened sense of connectivity, neighbors are working together to repair bicycles, identify native plants, share recipes, avoid plastic, support local agriculture, and take advantage of alternative transportation options.They also share more with each, provide assistance during emergencies, and enjoy block parties or potluck dinners together.

“During times of crisis, various systems fragment, fears run high, and turbulence takes over,” says Stayton. “What we need then is what Meg Wheatley calls ‘islands of sanity in the midst of a raging, disruptive sea.’ Wheatley insists that ‘there is no power for change greater than a community discovering what it cares about.’ If we build these connections with those living closest to us, we will find ourselves in a much better position when the next fire, flood, or hurricane hits. Those who are engaged in working for their community’s good can effectively challenge assumptions, influence decision-makers, and demonstrate that another world is possible.”

Photo Captions and Credits

1. Screenshot from a one-minute animated video introducing Transition Streets.

2. Tom Hoehn of Transition Fort Collins mentoring students in Colorado State University’s Green Renters program. Photo courtesy of Janice Lynne.

3. Members of a Transition Streets group in the Westbrae neighborhood of Berkeley, California. Photo courtesy of Linda Currie.