I was watching an episode of the science-fiction noir thriller “The Expanse” recently. Set hundreds of years in the future, the United Nations has now become the world government and its main rival is Mars, a former Earth colony. The UN is still in New York City and a new fancier UN building is now tucked safely behind a vast seawall that protects the city from rising water resulting from climate change.

It’s a world that looks like an extension of our own, but one that has survived the twin existential threats of climate change and resource depletion. But will it be so easy to update our infrastructure to overcome these threats?

The naive notion that we can, for example, “just use more air conditioning” as the globe warms betrays a perplexing misunderstanding of what we face. Even if one ignores the insanity of burning more climate-warming fossil fuels to make electricity for more air-conditioning, there is the embedded assumption that our current infrastructure with only minor modifications will withstand the pressures placed upon it in a future transformed by climate change and other depredations.

That assumption doesn’t square with the facts. Take, for instance, the Miami, Florida water system. One would think that Miami’s first task in adapting to climate change would be to defend its shores against sea-level rise. But it turns out that the most troublesome effect of sea-level rise is sea water infiltration into the aquifer which supplies the city’s water.

Once that happens the city would have to adopt desalination for its water supply, a process that currently costs two and one-half times more than current water purification processes. And, of course, desalinating water for a city as large as Miami, a city of more than 400,000 who consume 330 million gallons per day, would require a huge, expensive new infrastructure.

But the problems don’t end there. Superfund sites dot Miami and are already contaminating some of the water supply. The rising waters and more frequent floods will only make matters worse, requiring expensive decontamination equipment even before desalination becomes a necessity.

In addition, limestone mining allowed in many places leaves holes which quickly fill with water and allow much freer movement of chemicals through the aquifer.

At this point I feel like one of those late-night infomercials blaring, “But, wait there’s more!” That’s because the list keeps getting longer.

Developers have in many cases skipped expensive hook-ups with the area’s sewer system and opted for septic tanks. But as the water table rises due to sea-water infiltration and as flooding becomes more frequent, these tanks will increasingly be in contact with the city’s shallow aquifer. The writer of the linked piece above asks: Who will pay to hook up these households, and does it really make sense to hook up those households that in a decade or two may be underwater for significant periods during the year?

Which brings us to the next problem. The real estate boom in Miami will come to an end one day. A major slump in property prices could hit tax revenues making it more difficult for Miami to pay for climate change preparations. But the nightmare scenario is that the threat of climate change and sea-level rise could turn Miami from a destination city into a depopulating backwater with plummeting real estate values and contracting economic activity, and with all this happening “before the sea consumes a single house.” Who would pay for all the needed adaptation for those staying behind?

The interlocking nature of infrastructure, environmental change, economic activity and political institutions make the problem of adapting to climate change much more complex and expensive than most people and governments realize.

The problem elsewhere will not be one of too much water of the wrong kind, but of too little water to go around. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation which oversees federal water projects recently projected that Lake Mead which provides water to Arizona, Nevada and California has a one in five chance of dropping below 1,000 feet by 2026. That would trigger giant cuts to cities relying on the water; and that would be on top of cuts already made before reaching that level.

A further 100-foot drop would turn Lake Mead into what is called a deadpool behind Hoover Dam which formed the lake. That means no water would flow from the dam.

California and Nevada have already signed on to a plan to manage cuts and reduce water consumption. Arizona has so far refused, continuing to rely on existing water agreements to keep the water wolf at bay. Whereas Miami’s problems fall squarely on its municipal government to solve, the problems of water allocation in the southwestern United States are a multi-jurisdictional issue. The complexity of climate adaptation goes up exponentially when several official bodies must act in concert.

As for our hypothetical lover of air-conditioning whom I mentioned at the outset, even that amenity in most places depends on water. This is because thermal power plants including coal- and nuclear-fired facilities use lots of water to create steam to spin electricity generating turbines. That water must be cooled before it is returned to the rivers or lakes from which it is often drawn. That is the purpose of the large cooling towers from which plumes of steam constantly flow. Returning the water to its source without cooling it kills much of the marine life.

But, it’s hard to cool off hot water in a cooling tower when the outdoor temperature is also very hot. This is what was behind the shutdown this summer of nuclear reactors in France.

Sometimes the problem is just lack of water to run a power plant. This was the case in India in 2017 when a weak monsoon forced the shutdown of 18 plants for varying lengths of time from a few days to months. The electricity generation lost would have been enough to supply the island nation of Sri Lanka all of its electricity for a year.

This discussion, of course, only scratches the surface of all the water infrastructure that will be affected by climate change. I didn’t even mention the effects on the agricultural irrigation infrastructure (and the knock-on effect on food supplies). And, of course, I’ve said little about other types of infrastructure which are vulnerable as well and won’t be easily or cheaply fixed, if they are fixed at all.

Even more alarming is that, at least in the United States, we are starting with an infrastructure that has been very badly neglected—so badly that the American Society of Civil Engineers gave the country a D+ on its latest infrastructure report card. The organization estimated that the country needs to spend $4.5 trillion by 2025 just to bring its infrastructure up to good condition.

If the United States ever gets busy upgrading its infrastructure, perhaps it will include building a seawall to protect New York City as imagined by the creators of “The Expanse.” But I’d rather see the money spent first on securing our water systems for the simple reason that nothing, absolutely nothing in our society can function properly without a reliable, clean water supply.

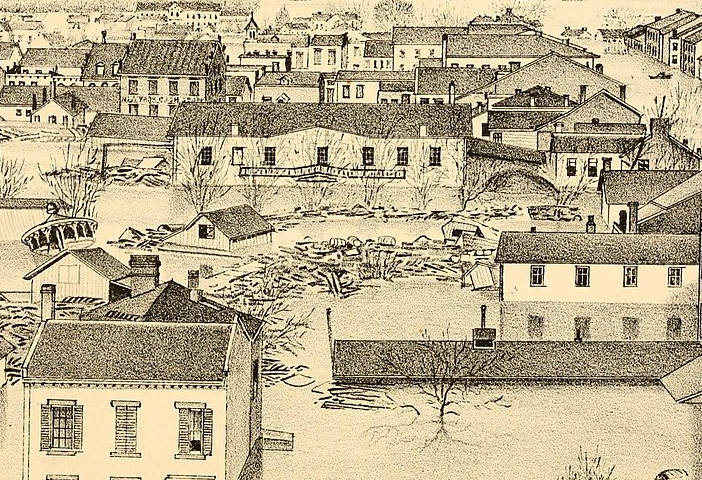

Image: Flood in the Ohio River Valley. From ” History of Dearborn and Ohio counties, Indiana” (1885). Via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:History_of_Dearborn_and_Ohio_counties,_Indiana_(1885)_(14801972633).jpg