Many of the severest crises we’re facing at present – e.g. climate instability, biodiversity collapse, the depletion of vital resources, and the dangerous compromise of ecosystem health through the spread of waste plastic and other pollution – stem directly from economic expansion hitting against ’hard’ limits in the physical world. And many other crises, such as violence in the Middle East, the plight of refugees, geopolitical sabre-rattling and the threat of wider global wars including nuclear war, can also at least partly be attributed to these hard limits.

To use a metaphor that’s become common among certain environmentalists, economic growth is acting as a planetary-level cancer. For example, the causal link between fossil fuel consumption and economic growth is well-documented and despite widespread claims to the contrary, evidence strongly suggests that decoupling growth from fossil fuel use, in absolute terms, will be pretty much impossible.

Clearly we would be far more likely to successfully eliminate greenhouse gas emissions – and also reduce other sources of dangerous pollution – if aggregate global economic growth were to be replaced by aggregate global economic contraction.

But isn’t growth necessary to progress and wellbeing? Shouldn’t growth – or at least, ‘green’ growth – be considered a desirable end in itself? Thankfully, these assumptions have been strongly challenged in recent years[1].

Money and growth

At present though there’s a serious technical problem with getting rid of aggregate economic growth – a problem hidden in plain sight:

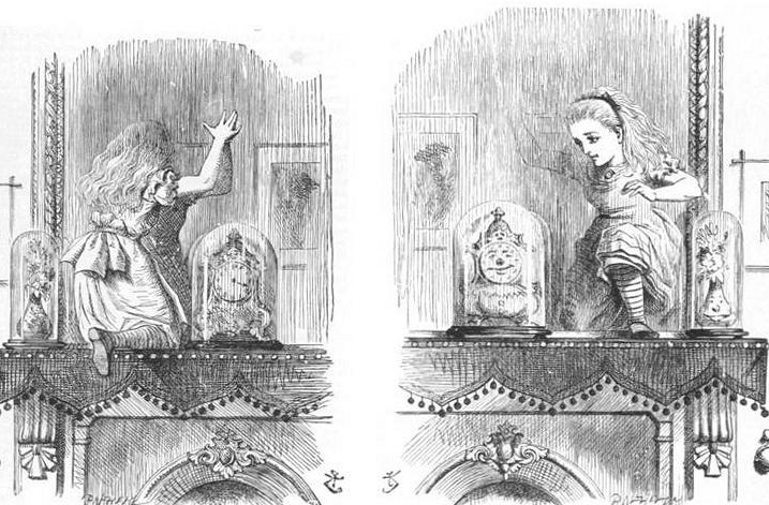

“Are we nearly there?’ Alice managed to pant out at last.

‘Nearly there!’ the Queen repeated. ‘Why, we passed it ten minutes ago! Faster!’

[…]

‘Well, in OUR country,’ said Alice, still panting a little, ‘you’d generally get to somewhere else—if you ran very fast for a long time, as we’ve been doing.’

‘A slow sort of country!’ said the Queen. ‘Now, HERE, you see, it takes all the running YOU can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!’

(From Through the Looking Glass by Lewis Carroll, chapter 2)

Since the global money supply is almost entirely created on a basis of debt, it needs aggregate growth to maintain itself. As Richard Douthwaite explained in his book The Ecology of Money, without continual growth (or inflation) there will not be enough money in circulation to enable our economies to function:

“…due to the way money is put into circulation, we have an economic system that needs to grow or inflate constantly. This is a major cause of our system’s continuous and insatiable need for economic growth, a need that must be satisfied regardless of whether the growth is proving beneficial. If ever growth fails to materialise and inflation does not occur, the money supply will contract and the economy will move into recession. Politicians naturally do not want inflations and recessions occurring during their periods in office so they work very closely with the business community to ensure that growth takes place. This is despite the damage that continual expansion is doing both to human society and the natural world.” .

To put it another way: in the present system, our need to have enough money circulating in the economy to enable us to function on a day to day basis is directly undermining the climate and other vital aspects of the global ecosystem.

So the financial system is playing the role of an economic carcinogen. Its basis in debt pressurises the economy to expand in a reckless, unbalanced manner that puts us (and other species) in extreme danger because it can’t acknowledge and adapt to the hard physical limits mentioned above.

It’s important to note however that in strong contrast to those hard physical limits, the financial system is actually ‘soft’. It’s a construct of the human mind. Despite what some economists might imply , it does not derive from the laws of physics or biology. It can be changed, it has in fact changed a great deal over history, and in recent years an increasing number of analysts have been calling for a further change: a shift away from debt-based, growth-dependent money issuance[2].

It’s true that their calls don’t always mention the growth dependency of the financial system. But they make other, equally valid arguments for reform, emphasising the need to improve financial stability by eliminating bank runs and lessening the frequency and extent of mass bankruptcies.

(I’m focussing in this article on campaigns for publicly-issued debt-free money. I’m aware that there’s a lively debate as to whether money issuance can ever be trusted to a small group of corruptible people, be they private bankers or bureaucrats, and that there’s also a need to clarify exactly in what manner new money, whether debt-based or debt-free, will first be spent into the economy, but I’ll leave those topics for another day.)

There’s the well-publicised Positive Money campaign in the UK, which is a member of the International Movement for Monetary Reform, bringing together groups from places as diverse as India and Puerto Rico. Positive Money campaigners advocate replacing privately-issued, debt-backed money with government-issued, debt-free money, which they called “sovereign money”.[3]

To many people’s surprise, an IMF working group published a paper in 2012, “The Chicago Plan Revisited”, which advocated 100% reserve-backed money – a position quite close, though not identical, to that taken by Positive Money (although it should be noted that the working group’s views do not represent the IMF as a whole). In Iceland, a 2014 report by an MP which proposed replacing bank-issued money with sovereign money also drew serious attention, including an endorsement in the leader editorial of the Financial Times. In Canada, a group has been pursuing legal action since 2011 to bring about monetary reform. Meanwhile in Ireland there is the Sensible Money campaign, and Feasta’s own Currency Group.

Most recently, in June of this year there was a referendum in Switzerland, organised by grassroots campaigners, for so-called ‘Vollgeld’, their term for sovereign money that would be issued debt-free by the Swiss central bank and that would replace privately-issued debt-based money. The proposal, coming out of left field in a conservative country with a deeply entrenched banking system, only got 24% of the vote. But it has triggered a well-overdue discussion about money creation in Switzerland and heightened the debate elsewhere.

The Swiss campaign was actually rather cautious. The campaigners advocated a gradual, and only partial, replacement of debt-based money by debt-free money. To ensure that the link between the money supply and growth is broken, a much bigger shift to debt-free money will be required (although it could be introduced gradually).

Despite the campaign’s caution, it was vociferously opposed by many private bankers, some economists and the Swiss central bank.

The opponents’ vehement reaction is unsurprising. From what I can make out, the economists who opposed the campaign didn’t take resource limitations into account at all in their calculations – they generally aren’t trained to do so, after all – and so they based their criticism solely on potential risks to financial stability and to innovation (also highly debatable criticisms, but they aren’t my main focus here). Private bankers stood to lose part of their shareholder profits if the reforms were enacted, so naturally they tended to oppose them.

Central banks and growth

Then there’s the Swiss central bank.

I think it’s worth exploring in more detail the role that central banks are playing in the money-issuance controversy. Central banks’ function is to try to keep the financial system stable. At present, a big part of this entails trying to keep the volatile, skittish speculative markets calm by insisting that the present system is working well (and downplaying the fact that it has already been modified countless times over history).

One could visualise a scenario whereby central bankers (or some of them, at least) acknowledged privately among themselves that a change to debt-free money issuance would be a good idea. But it’s extremely unlikely that they would come out and say so in public, or at least, that they would use those words. One could even argue that in the current circumstances it would be irresponsible on their part to do so, as it could rapidly trigger a financial panic.

However, it’s noteworthy that the Swiss central bank (called the Swiss National Bank) has now fallen into line with recent shifts in language that have also been adopted by the Bank of England and other leading financial institutions including the Bundesbank. In contrast to an earlier emphasis on the ‘financial intermediary’ function of banks, these institutions all now state clearly that private banks create money on a basis of debt[4].

This basic agreement on the fundamental facts is vital. Back when I did a masters thesis on central banking and sustainability in 2006, there was very little official recognition on the part of any government or central bank that private banks are directly responsible for money creation – although the Swedish central banker I interviewed for my research acknowledged it immediately when it came up, and if you looked hard enough you could already find references to it elsewhere too.

Although some might suspect a conspiracy behind such a widespread past misrepresentation of the function of private banks, I’d tend to just put it down to the fact that economists often downplay the importance of money, probably simply because they themselves are generally comfortably off[5]. Money’s role in the economy may be blindingly obvious to those who are less fortunate, but such people have tended to have far less influence on economic policy.

What central banks can do

Central bankers, whose remit is to maximise financial stability – and who would probably rather prefer for their grandchildren to be able to survive on a habitable planet than not – would have a much greater chance of actually achieving their goals if the way that money is issued was altered so as to relieve the pressure on the global economy to expand recklessly and hit against hard physical limits. They could bring about this alteration in a manner that lessens the risk of triggering a financial system panic by continuing to state publicly that the current system is viable and that they are only making minor adjustments to it.

They would need to use measured and highly technical language to describe the changes that they’re making. Happily, this is precisely the kind of language that they have so painstakingly developed in the course of the past four centuries.

I’m not being sarcastic or facetious in that last sentence (or not entirely, anyway). Nor am I suggesting that central bankers lie. Whether the proposed changes are to be considered radical or not depends very much on which angle you perceive them from. Yes, the replacement of debt-backed, privately-issued money with sovereign money would result in a considerable alteration in the private banks’ role in the economy. As argued in the IMF working group paper, it would probably lessen the frequency and magnitude of bank runs. It would probably also impede aggregate economic growth – but as we’ve seen, impeded (indeed, negative) aggregate growth is exactly what we need right now. It would not interfere with people’s ability to make day-to-day payments and to simply get on with their lives.

It would also help to prevent far more unquestionably radical – and extremely undesirable – changes in our environment.

To reiterate: central bankers don’t need to say publicly that they agree with the Vollgeld and other debt-free-money campaigns’ suggested reforms. In fact, it would probably be better if they didn’t do so.

And in turn, financial reform campaigners shouldn’t despair or let themselves become infuriated when they’re confronted with apparent intransigence from central bankers and other policymakers. They should bear in mind the surreal, through-the-looking-glass situation that the central bankers are in – and keep patiently plodding on regardless, making their case, with no expectation of any public acknowledgement of their point of view by officials.

I won’t embarrass myself by trying to suggest the sort of terminology central bankers and other financial policymakers might use when introducing reforms to money issuance – for obvious reasons, it’s better to leave that to others. Suffice to say that the sorts of minds that came up with the buzzwords listed on the Investopedia website can surely conjure up a diplomatic phrase or two.

(I also won’t discuss in detail here another, equally pressing need – the need to reduce the grotesquely disproportionate global power that is currently wielded by financial speculators – but will just mention that a shift to resource-based taxation, including site value tax, would make it much harder to transfer dodgy money to the Cayman Islands, and that the Attac movement’s proposed tax on financial speculation should help too.)

————

Eliminating the carcinogens from the economy’s financial bloodstream will not resolve our ecological crises all by itself. The hard physical limits will remain, meaning that we will still need to radically reform virtually all other sectors of the economy, particularly those that make intensive use of energy.

But changing our system of money issuance will remove a major obstacle that has been preventing the global economy from embarking on the detox that will be vital in order for deeper ecosystem healing to be able to kick in. As we’ve seen, the detox will need to include a considerable amount of aggregate economic contraction, but if well managed, this need not adversely affect the money supply and it could also – just possibly – eventually result in a stabler and fairer economy.

Eliminating physical toxins (and adapting our economy to other hard physical constraints) will become more feasible once we have got rid of the mental toxins that are blocking us from fully recognising and confronting the dangers we’re facing.

Endnotes

1. We’d probably all agree that some growth is necessary to some people. Clearly, justice and simple human decency require that deprived populations, particularly in low-income countries, should be able to expand their consumption to a point where they can live dignified lives. To balance this expansion out, the bloated economies of the industrialised countries will therefore need to contract somewhat more than they would otherwise. But provided there are enough resources available for our basic survival (no matter where we live), there’s plenty of evidence that growth does not automatically contribute to human wellbeing, and that aggregate growth is definitely not necessary for wellbeing. See for example here, here, here and here.

2. This wouldn’t so much be a step into the unknown as the reintroduction, in a modernised form, of money-issuance regulations that used to exist in various places and at various points in history before so much of our money became electronic in nature.

3. Positive Money campaigners have researched the relationship between money and growth dependency but they focus on the link between growth and the need to service debt, rather than on the link between the money supply’s very existence and growth, so their angle is a little different (but complementary to that of this article).

4. Like some other institutions, the Swiss National Bank puts the word ‘create’ in inverted commas. This strikes me as unnecessarily confusing. There’s no doubt that money is, in fact, created by private banks.

5. See Credo by Brian Davey, chapter 2

Featured image: Alice enters the looking glass, by Sir John Tenniel. Source