One of the most unique and vital museums in the Smithsonian network can be found in the heart of Washington, D.C.’s Anacostia neighborhood, a place long-neglected by government funds and all but forgotten by the city’s tourist crowds. Since its founding 50 years ago — when it became both the first Smithsonian museum located off the National Mall and the first federally-funded community museum in the country — the Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum has served as an interactive space, engaging local residents in the power of neighborhood storytelling.

In April, the museum launched a landmark exhibit called “A Right to the City,” which uses artifacts, photographs and oral histories to explore the history of activism and community organizing in six Washington, D.C. neighborhoods. The exhibit, which will be on display for the next two years, is a testament to the ways in which D.C. residents have fought to influence the forces shaping their city, particularly in a context of displacement and dispossession.

On my first visit to the exhibit, I was surprised to hear a security guard tell me, “I have lived in this neighborhood all my life and never knew all this happened.” But responses like that are precisely why chief curator Samir Meghelli worked on putting the exhibit together. I recently spoke with Meghelli to find out more about the exhibit’s impact on the community and the city as a whole. In the process, he told me about the little-known stories uncovered throughout the exhibit and the lessons these stories offer residents still fighting for their right to the city.

What inspired you to spend three years conducting research to create this exhibit?

The issues of neighborhood change and gentrification were very much a part of my own experience growing up. One of the focuses of this exhibition is the federal policy of urban renewal, which started in the 1950s [and continued] into the 1970s and 80s, and really led to the redevelopment — and ultimately the destruction of — a lot of cities across the country. I grew up in the city of New Haven, Connecticut, the city that received more urban renewal dollars per capita than any other city in the country. So I had a sense — both as a historian and as someone who grew up in a city shaped by these forces — of some of the broader structural issues that have shaped this city. To be able to document stories of Washingtonians who have spent their lives shaping the city, to tell this history from the perspective of folks who live here, was a transformative experience.

Why is the Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum the right place for this history to be told?

As we were looking toward our 50th anniversary, we wanted to develop an exhibition in the tradition of the museum’s work. Our work has always broached urgent social issues, and it has always been about developing exhibitions collaboratively with the communities whose history we’re sharing. There is probably no issue that has been as urgent and on peoples’ minds as neighborhood change and gentrification in Washington, D.C. So we started to explore how and why neighborhoods change and are transformed, but also how communities have mobilized in the face of that change to try to shape their neighborhoods in ways that best serve their needs and interests.

We wanted to feature neighborhoods from across the city that each tell different stories about change, but also about organizing and activism. We wanted to connect the much larger history of organizing to the contemporary moment — so people can draw lessons from the successes and failures of redevelopment policies, as well as organizing tactics.

The title of the exhibition, “A Right to the City,” is really raising a question: Do people have a right to the city? [Do they have a] right to exercise influence over the change that’s happening to their city? And do they have a right to access the resources and opportunities that a city provides?

What I think is distinctive at this museum is that our approach to building exhibitions is deeply collaborative. The history we’re telling in the exhibition is told from the perspective of the people who’ve lived in these neighborhoods and shaped these neighborhoods for years. We interviewed nearly 200 people from across the city — longtime residents, activists, organizers, architects, planners — to better document that history and share it in a way that is from a first-person perspective.

What are some stories from your research that can serve as inspiration to groups of organizers or activists still fighting for their right to the city today?

There are many largely untold stories throughout the city of really powerful and impactful organizing. In Anacostia, there are two groups that grew out of the organizing work of the Southeast Neighborhood House, which was founded in 1929 as a community center providing social services to displaced and low-income residents in Southwest. One group, called Rebels With A Cause, was an outgrowth of their work with young people east of the river. The Rebels got the city government to build more recreational facilities and to renovate older recreational facilities, including getting several Olympic-sized swimming pools built here. They had streetlights installed where there were pedestrian accidents. They had an after-school program and a police relations committee. They served as an important model for cities across the country who did similar work.

[The other group, called] the Band of Angels, was made up of the women residents of Barry Farm dwellings — which is public housing here in Anacostia. They were self-proclaimed “welfare mothers” who did organizing work around getting the city to repair and better maintain Barry Farm dwellings. A couple of the women also became some of the early founders of the city-wide Welfare Alliance and ultimately the National Welfare Rights Organization, which advocated locally and nationally around things like a guaranteed minimum income. [The Band of Angels pushed for] better and more public assistance, but also for things like dignity and justice for those receiving public assistance. So they ended up being really important, both locally and nationally.

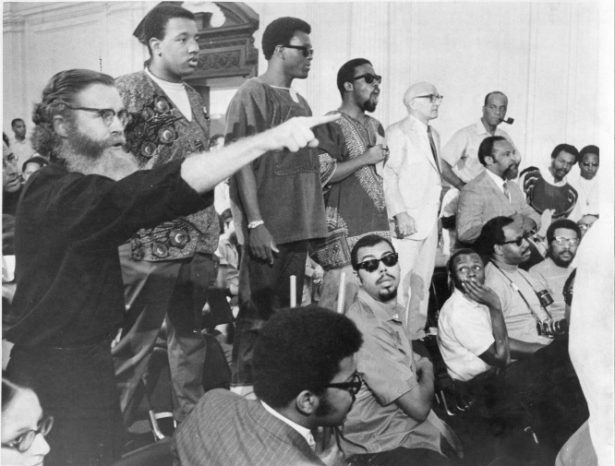

The Emergency Committee on the Transportation Crisis, centered in Brookland, standing up for the anti-freeway cause at a D.C. City Council meeting in 1969. (DC Public Library/Washington Post)

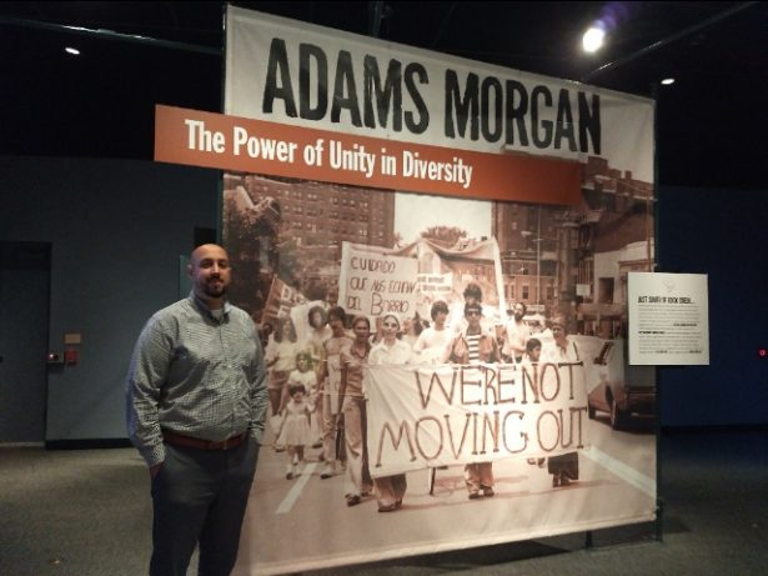

There are a lot of stories like that, where people living in these neighborhoods were able to do things that, at the time, seemed nearly impossible — things like defeating the North Central Freeway, which was going to cut through the entire city, until residents from [the neighborhood of] Brookland organized to fight its construction. There’s also the story of the Adams Morgan Organization, which created a literal neighborhood government at the time when the city had no elected city council or mayor. When the city did finally get home rule in the 1970s, what are today called the Advisory Neighborhood Commissions were in part modeled after the neighborhood government that the Adams Morgan Organization had set up. So there’s lots of stories like that that are too little known and reveal a rich history of organizing in this city.

One of the central features in this exhibit is previously unseen footage of a speech by Martin Luther King, Jr. during a 1967 visit to Washington, D.C. Could you tell us more about the significance of his visit and the message he gave to residents?

[The video is a] powerful window into this moment in the late 1960s, just a year before Dr. King’s assassination. He’s lending his support to what he calls one of the most important efforts happening anywhere in the country, led by residents in the neighborhood to devise a plan for the renewal of their neighborhood.

[King’s visit came about through his connection to] Reverend Walter Fontroy, who was born and raised in the Shaw neighborhood of Washington D.C. [Rev. Fontroy] saw what had happened in Southwest D.C. with [the federal policy of] “Urban Renewal,” and how it had resulted in the large-scale demolition and clearance of much of the neighborhood. It became clear to him that Shaw was another potential victim of that kind of urban renewal, so he helped create an organization called the Model Inner City Community Organization, or MICO, whose mission was to create a resident-led, small business owner-led redevelopment plan for the neighborhood. Part of their idea was to have urban renewal “with the people, by the people, for the people,” in contrast to the top-down federally-informed renewal that had destroyed much of Southwest.

Reverend Walter Fauntroy (right) reviews redevelopment plans for a block destroyed during the 1968 civil disturbances. (DC Public Library/Washington Post)

Rev. Fontroy had also served as the D.C. representative of Dr. King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference and helped organize the March on Washington in 1963. He invited Dr. King to come to Shaw to lead a parade from Dunbar High School to Cardozo High School, and to give a speech in support of MICO’s efforts to involve the residents in its redevelopment efforts.

In March of 1967, Dr. King led the parade through that neighborhood, which drew people of all ages. There were marching bands, beauty queens, all kinds of people involved in that parade. And in the speech that he gave at Cardozo High School, he had this refrain where he said, “Prepare to participate. Tell it in the pool rooms, tell it in the market, tell it in the town square. Prepare to participate.” He was really encouraging [the idea that] if this resident-led redevelopment plan is going to be successful, it would require the participation of the residents of the neighborhood. That idea is one we wanted to echo throughout this exhibition, and we wanted people to carry it with them when they left.

How do you hope this exhibit will impact the communities it features?

The idea of sharing these stories is really to inform people about a history that is too little known in a moment when that history is crucially needed. People three blocks away who have lived here all their lives can come and see their neighborhoods’ history recognized and celebrated, maybe even learn something. As part of the exhibition, we created a storytelling hotline that anyone can access by calling (202) 335-7288. We interviewed 200 people for the exhibition, and we wanted to share those stories, but also to let people record and share their own stories about their neighborhoods [for others to hear].

[The exhibit can also serve to educate] young people who are coming to D.C. for the first time to learn this city’s history, so they can start asking difficult questions about how it parallels to their own home communities. The questions we wrestle with in this exhibition are not just about the past, but about the present and about [creating] a more equitable and just future for our communities. Our ultimate hope is that people will leave better informed and inspired to engage more with these issues.