In the late 1990s in Northern California, we placed a photo of Liz (my late wife) and me, taken by the renowned photographer Annie Leibovitz, onto a quilt. Friends and family members gathered around and hand-sewed keepsakes of their lives with Liz into the cloth: bits of jewelry, ribbons, and personal messages.

By the time the black and white photograph, created for a national “Be Here for the Cure” AIDS campaign could be seen in magazines and writ large on subway walls, many of the people Leibovitz photographed would be dead: the cute guy, the sparky little kid, the strong transgender woman and the straight teenage girl. Few would make it for the cure.

People died by the thousands while the government turned a blind eye. Families mourned, shrouded in secrecy. The closest friends I will ever have grieved for each other even as they, too, prepared to die.

America as a whole seemed to shake itself awake only when thousands of AIDS Names Project Quilts were laid end-to-end on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., forming a master quilt strewn with names as far as the eye could manage—a seemingly endless landscape of unspeakable loss and undeniable love. Visitors dropped to their knees, humbled by such terrible beauty.

Now in my backyard, another quilt—the Migrant Quilt Project—continues to take shape. Now on show at the Pimeria Alta Museum in the border town of Nogales, Arizona, it is inspired in large part by the AIDS Quilt. The Migrant Quilt panels are traveling across the country and the artist/activist Jody Ipsen (the quilt’s originator) and Peggy Hazard (the project’s curator), along with many volunteer makers, hope for a similar impact on hearts and minds.

Women on the border often have a different take on immigration issues: more of a ‘tend and befriend’ approach, a kind of common sense, needle-to-fabric mend. The responses of women to the Migrant Quilt exhibit define the soft heart of what it means to be human. The day we visited, we watched female visitors leaving in tears.

“Docents had to go out and buy boxes of tissues” said Ipsen, “you cannot walk away from this without being moved.”

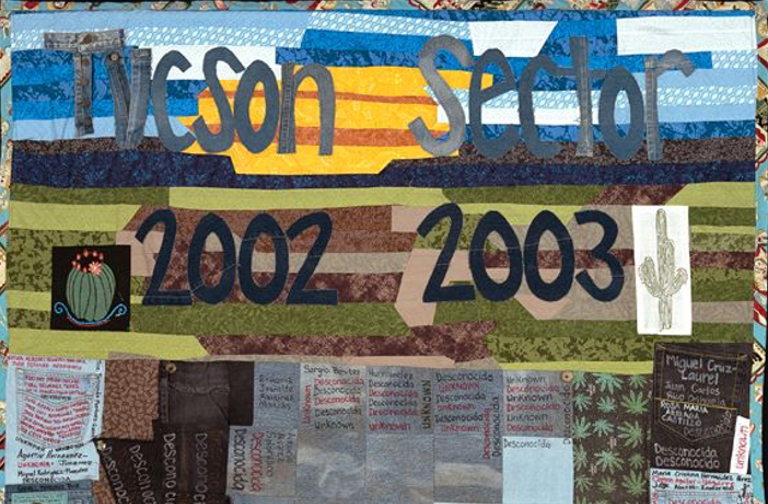

The 17 quilts in the project bear the names of people who have died each year crossing the desert in the Tucson Sector since 2000—the year the county medical examiner’s office began documenting the names of the dead, including unidentified remains. Patched together with denim, work shirts, embroidered cloth, and bandanas left behind on the desert floor, the quilts are scrappy in design and raw with truth.

Many of the bordados (embroidered cloths) stitched into the Migrant Quilts are inscribed with endearments. Contigo en la Distancia (With You Far Away) or Duerme Amor Mio (Sleep My Love) shock the viewer with familial intimacy. These personal embroideries, sometimes used as servilletas to carry food across the desert, are often blessed then sent along with a traveling family member. The embroideries have come a long way. Now they rest alongside the names of the deceased.

Each quilt represents countless lives lost on border ground, a hundred-mile strip of geography spanning two countries. The interstitial border region has morphed into a distinct culture of its own, and the quilts, with their binational contributors, fly its flag.

On the US side of the border, volunteers create each piece according to their own inspiration. Worn material migrates through the quilts and melds in the viewer’s eye. Names of the dead rise off the surface in bas-relief like rogue wildflowers pushing up through the desert floor, commanding the same kind of attention as the white crosses we see strung with wire in and around the slats of the border wall.

“Quilts have traditionally been made to memorialize loved ones who died,” said Curator Hazard, “and also, to raise consciousness.” In the Nineteenth century, women used quilts not only to raise funds for the anti-slavery movement, but to express their feelings about slavery.

Memory is the first form of resistance, and quilt-making—a primary tool of resistance and remembrance—stands the test of time. At QuiltCon 2018, the Modern Quilt Guild’s annual convention, the exhibits were honeycombed with activist quilts. The resurgence in “truth textiles” also carries on at the Social Justice Sewing Academy, which empowers youth activists for social change.

The humblest materials can communicate what cannot be said in dangerous times, can comfort the family, and can mourn the dead. Quilting, embroidery, and applique—arts of hearth and home—remain a language shared.

Two decades ago in Northern California, our fragile but fierce community took turns stitching Liz’s favorite piece of mud cloth onto a quilt. I remember the silence that day as we worked together, united in the province of memory. Craig, Liz’s long-time brother-in-arms, his large brown eyes brimming with tears, leaned over and carefully sewed a cowrie shell onto the fabric. Craig would be the next to die.

Now, on our southern border, our neighbors continue to die crossing cultures. The personal is political and the political is spiritual. Rather than ask “How do we build higher walls?” we are best served as people to ask, “How do we meet?” and “How do we mourn?”

The root of the word ‘memory’ stems from the word ‘mourn.’ The devotional art of making quilts in the service of others allows us on the US side of the border wall to touch the essence of the Other, to offer witness, and to mourn.

The Migrant Quilt Project succeeds where rhetoric fails. Pinning and stitching, working the cloth to make sure the dead are not forgotten, these quilt-makers trust that no one turns a blind eye.

This article was first published in Kosmos Journal.

The Migrant Quilts are on exhibit at the New England Quilt Museum in Lowell, Massachusetts, through July 15. After that, they will travel to Michigan and Illinois. See here for the exhibit schedule and more information.

Teaser photo credit: Migrant Quilt Project Facebook page.