This essay is available in the latest edition of Red Pepper Magazine.

Subscribe now for the latest in news, views and cutting-edge analysis.

In 1792, pioneering British feminist and social justice activist Mary Wollstonecroft wrote in her seminal book The Rights of Women, ‘It is justice, not charity, that is wanting in the world.’ Two centuries later, the shadow international development minister, Kate Osamor, a black feminist with a background in social justice activism, has anchored that fundamental truth in Labour’s vision for international development, ‘A World For the Many, Not The Few’. In doing so, she has committed the Labour Party to putting social justice at the heart of its international agenda and listening to the voices of those facing the greatest injustices: women in the global south.

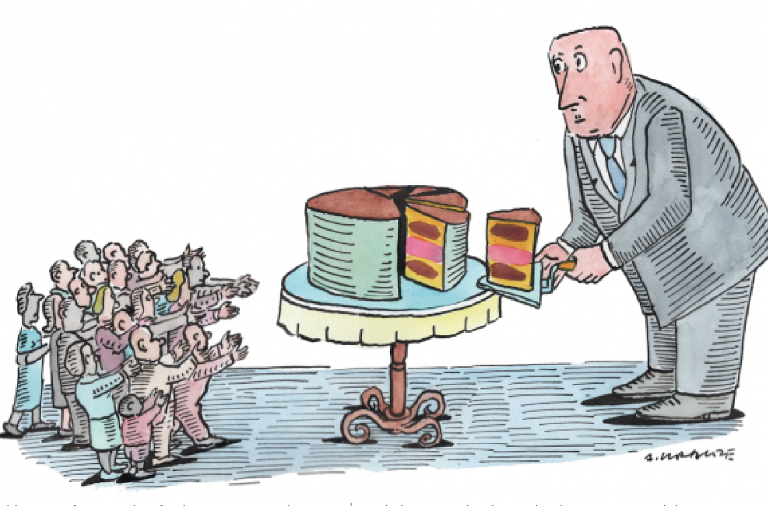

For too long, politicians and, to their shame, many in the development sector have ignored the key driver of global poverty: neoliberal capitalism, a failed economic system whose rules are stacked in favour of corporate elites. They have stayed silent on the culpability of Britain in promoting unfair trade rules, creating new debt burdens, forcing privatisations and entrenching oppressive neo-colonial power dynamics on the international stage.

The new colonialism

The idea of ‘international development’ was constructed in the post-war era to cover up the deliberate ‘underdevelopment’ of the global south. During colonialism, Britain and the other industrial powerhouses had enriched themselves by extracting resources and slave labour from their colonies. They deliberately impoverished the south and, in the process, killed countless millions across Latin America, Africa and Asia. It is estimated that the UK extracted £600 trillion during its colonisation of India alone, reducing India’s pre-colonial share of the global economy from 27 per cent to just 3 per cent by the time the British left.

This system financed the industrial revolution and two world wars. But colonial power was severely weakened by the costs of the second world war and faced the existential threat of powerful liberation movements, which were demanding economic justice, democracy and human rights – and were prepared to fight for them.

Decolonisation and the rise of independent political movements across the global south replaced the old colonial relations with a new framework. Between 1950 and 1970, southern governments began to promote their own independent, state-led development agendas to build and protect their economies, to redistribute wealth and invest in public spending on health and education. They adopted policies that started to see poverty fall and the gap between rich and poorer countries begin to close. Western corporations would no longer be allowed to enrich themselves by exploiting the former colonies, looting their resources or profiting from cheap labour.

With their economic interests threatened, western governments began a new era of imperialism marked by violence against the global south, overthrowing democratically-elected governments from Mossadegh in Iran and Arbenz in Guatemala to the bloody assassination of Patrice Lumumba of Congo, his body chopped up and burnt on the orders of the USA and Belgium. The US-backed coup against Sukarno in Indonesia led to close to a million of his supporters being killed under the military dictatorship of Suharto. Brutal dictators were installed across the south, propped up by aid to facilitate the continuing looting by the west.

The rise of neoliberalism in the 1970s saw a shift towards more extreme free-market thinking. The basic idea was that by enriching corporations and the already wealthy, economic benefits would ‘trickle down’ to the poorest and ultimately eradicate poverty. This provided the justification for forcing so-called structural adjustment programmes onto the former colonies – policies that forced open economies, cut social spending and continued to enrich former colonial powers. Neoliberal states, the UK and US first among them, were able to use ‘foreign aid’ to fund privatisation and expand their corporations’ control over resources.

Colonialism had allowed western powers to enrich themselves by directly and violently extracting resources and slave labour from their colonies. Under neo-colonialism, wealth was extracted through financial flows made possible by a network of tax havens; exploitative lending and debt repayments; repatriation of profits from multinational companies; the creeping privatisation of public services and infrastructure; and the unbridled extraction of natural resources, the environmental impact of which contributes to the very ‘natural’ disasters western NGOs are sent in to relieve. The US-based Global Financial Integrity (GFI) non-profit research group estimates that since 1980, $26.5 trillion flowed out of the global south to enrich the west – dwarfing the aid being offered by those same western governments.

Any hope of progressive reforms was systematically blocked by the neo-colonial system. From land and agricultural reforms and public investment to deciding their own finance, trade and labour policies, the most significant decisions facing the newly sovereign states were snatched away by the colonial powers who had just ‘granted’ them their independence. And the west made the choices that would preserve its dominance into the new age, wielding the power of IMF, the World Bank and the WTO to impose its will as it desired.

Looked at in the context of neo-colonial globalisation, it becomes clear how polluted mainstream ideas about development really are. The very notion of ‘charity’ erases a global history of slavery and oppression, reinforcing racist and patriarchal ideas and depriving people across the global south of any agency – instead promoting the idea that poverty was a natural state and not one deliberately engineered by the west. At its heart it upholds rather than challenges the old dynamic of the global north as teacher, leader and disciplinarian, and the global south as a child, subject and deviant, who should be grateful for any help it gets. The charity-development approach has peddled little more than poverty porn and free-market dogma for the past half century. At best, it promotes the myth that charity can address the political and economic systems that preserve poverty in the 21st century; at worst, it’s just a polite way of casting white saviours as the heroes of a story in which Black Lives Don’t Matter and Neither Do Black Ideas.

Change in the landscape

After decades in which the only thing that’s changed has been the language, The World for the Many, Not the Few represents a change in the landscape. This new policy presents a radically different vision for how the UK should approach international development. It pinpoints the greatest challenges to a just and sustainable approach: enduring poverty and soaring inequality; public services under siege; a climate crisis threatening lives and livelihoods and forcing mass migration; and everywhere, women bearing the brunt of the burden.

These challenges are not new. War on Want has been campaigning on these issues since its foundation. In 1952, it launched with a leaflet that said: ‘Transcending all our immediate problems, this gap between the rich and the poor of the earth is the supreme challenge of the next 50 years.’ It was often one of the few organisations willing to tackle the root causes of poverty and inequality around the world: colonialism, imperialism and, later, neoliberalism. Now, after just over 60 years, not only has the IMF been forced to admit the significance of global inequality, we’re in with a chance of a British government that understands this reality – and is prepared to act on it.

About time too, because successive UK governments, both Labour and Conservative, have been among the chief architects of neo-colonialism. From the 1970s both aid and export credits were tied to the procurement of British goods and services. The 1997 Labour government did reduce the amount of aid tied in this way, and the International Development Act 2002 clarified the purpose of aid spending as poverty reduction, but this led to limited change in practice.

The neoliberal dogma championed by the UK’s Department for International Development (DfID) prohibited any questioning of the systemic causes of poverty. That way, the UK could continue promoting its policies of globalisation, unjust trade rules, forced privatisation, deregulation and tokenistic charity, while simultaneously appearing to be eradicating global poverty.

UK aid money helped force privatisation onto fragile states. Rendered economically dependent by a global system designed to keep them that way, they were in no position to refuse the poisonous medicine being offered. One by one, countries lost their energy, water, healthcare and education systems to a private market dominated by their former colonisers.

For example, DfID has spent hundreds of millions of pounds of taxpayers’ money to expand corporate control over agriculture in Africa. This has continued for years, unknown to the public, primarily because most charities and NGOs won’t discuss it. War on Want’s 2012 report, The Hunger Games, exposed how vast tracts of farmland were handed over to private investors. DfID sought to bring millions of African farmers under the control of the world’s largest agribusiness companies by rendering them dependent on corporate-controlled seeds and chemicals. The result? Rising debt, hunger and poverty among rural communities and a far more fragile food system, increasingly vulnerable to fluctuations in the market and climate.

This ‘food security’ agenda argues that the world’s food production is safest in the hands of a few megalithic agribusiness corporations. It is kept alive by a revolving door of self-interested appointments and personal connections that ensure DfID remains close to the corporations that benefit from its assistance. It’s a familiar pattern across all areas of international development.

While enforcing a pro-corporate development model abroad, the UK simultaneously created a hostile environment at home for any organisation that dared question it. The Charity Commission is tasked with disciplining the sector, so, in the words of one of its board members, NGOs focused on ‘knitting jumpers and organising jumble sales’ rather than public campaigning. This, combined with the Lobbying Act and anti-advocacy clauses for those receiving public money, cowed most charities into silence.

Vision and ambition

What is new and potentially groundbreaking is the vision and ambition of Labour’s new policy paper, A World for the Many, Not the Few. The paper’s most important proposals include: making inequality reduction a binding commitment for the DfID; democratising global financial institutions dominated overwhelmingly by the wealthiest states; tackling climate change by promoting energy democracy; and reversing the privatisation of aid spending and public services.

The paper also puts feminist principles where they belong, at the heart of international development strategy. This is of profound importance not only because women are the hardest hit by poverty but because they are the most powerful agents of change and real empowerment for women has proven to be one of the most effective tools for fighting poverty as a whole.

Beneath all this lies a commitment to social justice that promises to take international development away from the charitable model and towards one that could transform the rules of a global system rigged to benefit the rich.

This would have some profound implications. For decades, overseas aid spending has been used to promote neoliberalism in and control over the global south. After powerful movements across the south liberated themselves from direct military and colonial control, economic control through a neo-colonial development model preserved the dynamic of domination by the north. Since the rise of neoliberalism in the 1970s, this system has held back human rights and living standards in the former colonies while preserving the rights of a global elite to exploit land, labour and resources in poorer countries.

Labour’s exciting step forwards hasn’t come from nowhere. The policy is so ambitious only because it has emerged from dialogue, not just with a panel of academic experts but those with decades of experience working with social movements and grassroots groups on the frontlines of social justice struggle.

For example, when I was invited to a seat at the table of Kate Osamor’s taskforce, I brought with me the experience and principles of my long-time partners La Via Campesina, the world’s largest peasant movement and most powerful opponent of corporate agriculture, uniting farmers across 70 countries. These are the keepers of and fighters for a powerful and inspiring alternative, based on agro-ecology and food sovereignty. By centring voices from the global south and being sensitive to the connections between gender, race, class and other forms of discrimination that conspire to marginalise and oppress, Kate Osamor ensured that taskforce members with roots in these movements could feed their thinking into the policy.

The echoes of radical voices can be heard throughout the proposals, not least in the assertion that any genuine commitment towards eradicating poverty and contributing to a more equal and peaceful world will need all government departments to join the effort. It’s no good having the Department for International Development advocating for human rights or peace-making efforts while the Foreign Office is fuelling a global arms trade and the Home Office is calling for taller walls around Fortress Europe for those of us who wear ‘our passports on our faces’. That is why the policy paper is calling for coherence across government and strategic initiatives on key issues such as trade, taxation and international debt as well as the arms trade.

One step on the road

Of course, this is just one step on a much longer road. One notable omission is the policy’s failure to address the role of the Commonwealth Development Corporation (CDC). No critique of neoliberal development policy is complete without reference to DfID’s private-sector counterpart. The CDC has long been using public money to fund high-risk investments and profit from poverty in the global south. Its use of tax havens and its connection to labour and land rights abuses has been well documented by War on Want and others. As a private equity firm concerned first with returns on investments, it is a travesty that the CDC is tasked with carrying out overseas development to alleviate poverty.

Another glaring omission is any reference to reparations. The policy does reiterate Labour’s commitment to the Paris Agreement, which calls on the north, which is disproportionately responsible for global warming, to invest in the south’s transition from fossil fuels and mitigate associated economic costs. However, it makes no reference to the reparations owed by right to the south for centuries of slavery and colonialism, or the climate debt owed by western nations for causing the climate crisis. Moving from a discourse based on aid, and articulated through ‘poverty porn’ that reinforces racialised and gendered stereotypes, to one rooted in responsibility and justice for this past, remains the next step Labour has yet to take.

By calling for a reduced emphasis on economic growth as the sole measure of success for development projects, however, this ambitious new policy strives to redefine development. As it stands, the proposals face a multitude of formidable obstacles: a battle for hearts and minds in the face of rising poverty at home, a divisive right-wing media and politicians who dream of constituting a new Empire 2.0; a global development model built along neo-colonial and neoliberal lines of infinite growth on a finite planet; and a ferocious backlash against feminist principles, particularly when articulated by women of colour.

Beyond all this, we are right to question what might happen when the idealism of ‘a world for the many’ collides with the interests of the City of London and UK multinationals with everything to lose. But for the first time in a long time, we have a development secretary waiting in the wings with real answers to questions on international development that many in the global south had long given up even bothering to ask us. Kate Osamor believes we can do more than loaning British money to mop up a fraction of the damage done by British bombs. And she should be applauded for asserting that women are not just the hardest hit by poverty but also the most powerful agents of change.

Frantz Fanon once said, ‘The wealth of the imperialist nations is also our wealth. Europe is literally the creation of the Third World. The riches which are choking it are those plundered from the underdeveloped peoples. So we will not accept aid for the underdeveloped countries as “charity”. Such aid must be considered the final stage of a dual consciousness – the consciousness of the colonised that it is their due, and the consciousness of the capitalist powers that effectively they must pay up.’

For the first time in a long time, a step forward has been taken in Westminster to make real Fanon’s demand for a new consciousness. But to turn those policy proposals into more than just words requires a movement of people in the UK willing to promote a new internationalism, refusing to locate its politics only domestically, dedicated to realising the right of all people to a dignified life, and accountable to those on the frontline of struggle – a genuinely intersectional movement for global justice.

Teaser photo credit: Illustration by Andrzej Krauze