Seven months after Juan and Jonathan Leija were forced to evacuate their flooded homes during Hurricane Harvey, the cousins face challenges that go beyond just recovering their lives. Building back isn’t easy for anybody, but the Leijas are doing it as looming policy decisions threaten to uproot them again.

Juan and Jonathan are Dreamers — young adults who qualified for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, the Obama-era policy that granted clemency to undocumented immigrants who arrived in the United States as children. In September, President Donald Trump announced he was canceling the program, leaving it up to Congress to pass legislation on the issue — which it hasn’t been able to agree on.

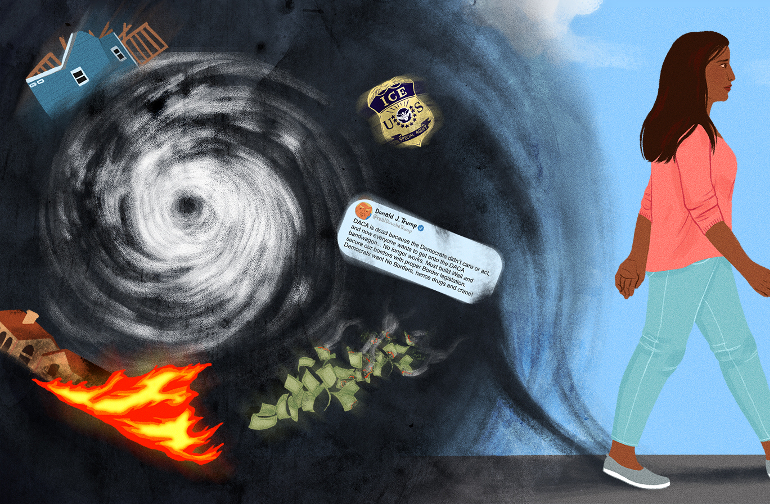

Undocumented immigrants were hit especially hard by last year’s devastating hurricanes and wildfires. Immigrant populations were already struggling with higher rates of poverty and less access to medical care. Then storms, fires, and mudslides wiped out homes and disrupted industries like agriculture that employ a largely immigrant labor force. Despite the dire need for relief, undocumented immigrants are ineligible for federal disaster aid. Some were afraid to even go to emergency shelters or reach out for help out of fear of exposing their own or a relative’s immigration status. Post-disaster, many immigrants have turned to jobs in construction and face injury and exploitation rebuilding communities that were leveled.

“Yesterday was the first time since Harvey that it rained really hard,” Juan told Grist in March. “It definitely brought flashbacks and it triggered a little bit in me. And just to add onto it, tomorrow a year from now my DACA expires.”

While undocumented immigrants like Juan work to pick up the pieces after disaster, the Trump administration is placing targets on their backs. In addition to ending DACA, Trump has revoked Temporary Protected Status for countries at a faster pace than any other president and has intensified immigration raids, even in sanctuary cities, over the past year. For some immigrant Americans, it’s political insult to climate change-induced injury — and suggests that it may be a while before they find a measure of stability in the U.S. again.

When Hurricane Harvey struck the Houston area, it brought with it a year’s worth of rainfall over in less than a week. The storm affected 13 million people across Texas and Louisiana, killing 88. Causing $125 billion in damage, Harvey was the second costliest storm (behind Hurricane Katrina) to hit the U.S. since 1900.

Ten days after Harvey made landfall in Texas, President Trump announced an end date for DACA the following March.

“I was angry. I was confused. I was sad. I was anxious,” Juan Leija recalls. “I thought it was really heartless for him to do that after a national travesty.”

Harvey hit Juan’s family’s home hard. The Houston house they rent flooded up to his thighs. Juan is 6’1’’ and says the water level was probably above his mom’s waist. The family evacuated. They waded through water for two miles before reaching a friend’s home. For the next four months, Juan, his two siblings, his mother, and her boyfriend squeezed into a one-bedroom apartment.

The Leijas joined hundreds of Texas families struggling to rebuild after the storm. While Harvey swamped all of Houston, its impacts were not felt equally.

“In terms of the extent of hardship or suffering, we definitely found disparities across racial, ethnic lines, and across income lines,” said Shao-Chee Sim, a researcher at the Texas-based advocacy group Episcopal Health Foundation, who helped lead a study of adults living in Harvey-damaged counties.

The survey found that, after Harvey, 64 percent of immigrants suffered unemployment and income losses compared to 39 percent of their U.S.-born neighbors. Immigrants were also more likely to have fallen behind on their rent as a result of the storm and were more than twice as likely to have had to borrow money from a family member or payday lender in order to make ends meet.

When Juan’s cousin Jonathan’s mobile home flooded, it was a huge setback. “Basically, we had to remodel everything,” he said. “That was going to cost money that we didn’t have.”

Undocumented immigrants — including Dreamers — are ineligible for aid provided in the wake of natural disasters by the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Families with mixed immigration status, however, do qualify because parents can apply for relief on behalf of their U.S. citizen children. Even so, many eligible families avoided applying due to worries over providing personal information in an aid application. FEMA is, after all, an agency housed within the Department of Homeland Security, which also oversees Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

“In an immigrant community there is a huge concern about asking for aid because there is a fear — and a legitimate one — about, ‘will this come back to hurt my chances of gaining status at some point in the future?’” Kate Vickery, executive director of Houston Immigration Legal Services Collaborative, said. “The answer has always been complicated, but under the Trump administration, it is pretty grim.”

Jonathan Leija’s younger siblings are U.S. citizens, and the family decided to apply for FEMA assistance. The officer who came to inspect their home canceled four separate appointments before finally showing up.

Jonathan, who is studying construction management at Lone Star Community College, north of Houston, missed class twice in order to be home for appointments that never happened. Before Harvey hit, Jonathan had to withdraw from school for a semester to save up money for tuition. Dreamers don’t receive federal financial aid, so he took up jobs roofing and working at a tire shop so that he could get back to class. The storm posed more delays and after all the missed appointments, his family’s FEMA application was denied.

Still, Jonathan counts himself lucky. A grassroots organization that defends workers’ rights, Fe y Justicia Worker Center, sent contractors to his home to repair the damage. That kind of help can be a godsend for undocumented immigrants who work in industries hit hard by flooding and fires. Immigrant-rights advocates are anticipating that those who lost employment because of last year’s disasters might seek out construction work as part of the rebuilding efforts.

Vickery, with Houston Immigration Legal Services Collaborative, warns that undocumented immigrants are disproportionately part of what she calls the “second responder wave.” “They are the labor force doing the cleanup,” she explained.

The rebuilding booms that follow disasters come with their own threats. More than a third of day laborers informally employed in construction in the first few weeks after Harvey said they were injured on the job, according to a study conducted by the University of Illinois at Chicago. Two-thirds of the respondents said that their workplace was unsafe. Eighty-five percent of day laborers who worked in hurricane-affected areas reported not receiving any training for the worksites they entered, and nearly two-thirds did not even have a hard hat to wear. Aside from all the safety risks, the study also found that more than a quarter of workers had experienced wage theft.

“The vulnerability of being a worker in a disaster recovery area if you don’t have status is a huge issue,” Vickery said.

Advocates in California are also concerned about the risks workers are facing after the state’s massive fires last year.

“A lot of people going into that labor might not have worked in construction. Those people need training,” said Christy Lubin with the Graton Day Labor Center.

Months after the blazes, many immigrants employed in affected industries — including agriculture, hospitality, and domestic work — have lost their homes and their jobs.

“A lot of people see wildfires in the hillsides of California or mudslides in affluent communities like Montecito as largely affecting wealthy homeowners,” said Lucas Zucker with the grassroots organization Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy (CAUSE). “The reality is those wealthy homeowners employ domestic workers who are largely undocumented. They get no attention and really have nowhere to turn.”

In Santa Paula, an hour and a half northwest of Los Angeles, Marisol, a mother of three, and her family are still recovering from the Thomas Fire, which burned down their home in December. Marisol’s husband had worked on a horse ranch and wasn’t allowed time off to help his family after the wildfire. He lost his job as a result. Fearful of applying for aid that would require them to disclose their undocumented status, Marisol (whose name has been changed to protect her identity) and her husband are trying to get back on their feet with fewer resources available to them — and while U.S. immigration enforcement efforts intensify.

Like the Leija cousins, Marisol came to the U.S. from Mexico as a child — but she didn’t qualify for DACA because she doesn’t have a high school diploma, something she’s still working toward now. Her children, however, were born in the U.S. and are citizens.

“I don’t like to think about the consequences if me and my husband aren’t here,” Marisol told Grist through an interpreter as she fought back tears.

Undocumented folks and immigrant-rights groups have felt overwhelmed by the barrage of executive actions and policies targeting immigrants since Trump came into office. Deportations were already high under the Obama administration, but they jumped in the first year of Trump’s presidency. The number of people living in the United States who were deported rose nearly 25 percent, from roughly 65,000 in 2016 to more than 81,000 people in 2017.

For some migrants who received Temporary Protected Status because of a natural disaster that affected their home country, the experience of disaster and displacement is becoming a cycle — especially as climate change exacerbates extreme weather events. TPS is the only U.S. policy offering sanctuary to people displaced by environmental calamity, and Trump has been chipping away at the program by removing five countries designated for TPS, including Haiti and El Salvador, within the past year. More than 320,000 people could become undocumented as a result.

“We’ve kind of been in perpetual crisis mode for the last year as we’ve dealt with the disaster of the Trump administration on our communities to the literal disaster of wildfires and mudslides,” says CAUSE’s Zucker. “Immigrant families are basically caught in the middle of being under siege by the government and in desperate need of the government basically unwilling to provide that assistance.”

Marisol and her family in California got some much-needed financial help from an “UndocuFund” created by CAUSE and other groups, which provides grants to families affected by the raging wildfires and mudslides in California last year. But needs are still outpacing donations, and there are more than 800 disaster survivors awaiting assistance.

Meanwhile, back in Texas, Juan and Jonathan Leija are determined to keep moving forward. If Jonathan’s DACA status expires before Congress passes measures to replace the program, he’ll likely lose his job at the tire shop where he currently works. That will mean he will have to find another way to pay his way through school.

“Whatever happens, happens,” he said. “I’m still going to find a way to go to school, to finish it.”

Without DACA, Juan may be unable to find lawful employment even after graduating — but he doesn’t hesitate to speak out. Since before DACA was implemented, one of the Dreamers’ rallying calls has been “Undocumented and Unafraid.” He still wants to replace fear with hope.

“I don’t want Dreamers to feel like they have to get back to the shadows.”