Media savant Marshall McLuhan coined the term “global village” in 1962 in his book The Gutenberg Galaxy. Today, we take the concept of an electronically connected global population with instant access to practically every plugged-in person on the planet as a fact of life.

We often see our global village as a force for good, creating understanding and binding people across cultures regardless of distance. McLuhan saw the downside as well. In his book he notes:

Instead of tending towards a vast Alexandrian library the world has become a computer, an electronic brain, exactly as an infantile piece of science fiction. And as our senses have gone outside us, Big Brother goes inside. So, unless aware of this dynamic, we shall at once move into a phase of panic terrors, exactly befitting a small world of tribal drums, total interdependence, and superimposed co-existence.

It turns out that the global village has many key similarities to an actual village or small town. Fellow villagers and small town neighbors are much more likely to know about each other’s personal lives (often including many of the intimate details) than those who live in a large city. The anonymity and privacy today which so many prize and enjoy in the big city is quickly being eroded in the new surveillance economy. Living in the global village can now subject us to the same kind of scrutiny which those in small towns and villages have long been accustomed.

I say “economy” because the information collected on humans in the 21st century involves not just “Big Brother,” a term invented by writer George Orwell for an all-seeing authoritarian government, but also commercial enterprises which collect details on our lives—details available from our commercial dealings and publicly recorded acts (land sales and voting, for example) and other details which we voluntarily surrender to such sites as Facebook and LinkedIn.

We are now having a surprisingly involved public discussion about what personal information we want to be publicly available and about what control each of us should have over that information. We often use the term “personal data” because our information goes into vast databases constructed by commercial and governmental entities.

Part of the problem is that the data thus catalogued doesn’t give a nuanced picture of who each of us is. In an actual small town or village, the banker, for example, may know us personally and be able to judge our character as a factor in granting or not granting a loan. Today, the banker may be an automaton, a lending website relying on a credit score and some other information in databases that say little about who we are.

The example brings up precisely the conundrum we face: In order to have the convenience and speed we want in accessing the goods and services we seek, we make personal data available to a wide variety of entities. We do this in part because those entities cannot otherwise make a judgement about our needs or our trustworthiness. Regular personal encounters are not part of the equation. The global village turns out to be a very incomplete replica of an actual village.

We cannot, however, become aware of products and services that might interest us if the sellers do not reach us with their marketing campaigns. And as a mass society, we communicate with government about a host of issues via email and other electronic communications. In fact, we now have our first president who conducts policy announcements—sometimes to the surprise of his staff—via Twitter.

The global village increasingly has its consequences for public officials and corporate managers who have previously escaped the kind of scrutiny that a combination of leakers, hackers and the Internet can now bring. Wikileaks is but the most visible example. Edward Snowden, the famous National Security Agency whistleblower, carried a vast trove of electronic secrets out of the agency on a small flash drive before making them available to reporters for worldwide distribution.

But then there is just excellent investigative work aided by the Internet. The exposure of Exxon’s research on climate change, most of which was publicly available in archives, only came to the surface with an Internet search that connected reporters to the right people.

You might call this an invasion of Exxon’s privacy. But most people call it good journalism that holds corporations accountable.

We do monitoring of another type every day and think little of it. We monitor machines in workplaces that make the products we use. We monitor pipelines that carry oil and natural gas to refineries and natural gas to homes. We monitor developments around the planet such as temperatures on the North and South Poles, the acidity of the ocean and the carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere to study climate change.

Our industrial monitoring is done for reasons of safety and efficiency. Our monitoring of the planet is done for discovery and to inform policy. All of this is another type of surveillance. It’s no good to say that this monitoring is only of nonhuman objects. First, our industrial infrastructure is run by people and those people are called to account when something that’s not supposed to happen does. Second, monitoring the atmosphere is indirectly monitoring the activities of human beings since human activity is the main cause of climate change.

We live in an age of surveillance because without it we could not effectively and efficiency run the complex systems we have built; and, we would not be able to monitor effectively the wildly complex worldwide climate system in order to ascertain its true state and the reasons behind the changes we are witnessing. Even the sky itself must feel that the global village has arrived.

Our incessant desire for data is a function of the complex systems we now rely on for the smooth functioning of our technical society. We will find it increasingly difficult to separate our private lives from our public ones as they merge under the pressures of the global village.

To escape such pressures the individual would have to give up some of the functionality available from modern communications technology. There are people who could afford cellphones but refuse to use them. I know a couple who refuse to use email. They have a lively set of friends from all over the world without it. But they must forego the instantaneous written exchange of the email for the more languorous pleasures of the letter.

Governments, of course, take advantage of the electronic ecosystem that has grown up around our enhanced communications capability. They want to know what’s going on to prevent terrorism or criminal fraud or tax evasion. Somewhere in all that data supposedly is the key to keeping the nation and its people safe. But the potential of all that personal information to cast any of us in an unfavorable light—especially when that information is taken out of context—has been and will continue to be too tempting for leaders intent on destroying their political opponents and controlling their people.

The price of our ubiquitous information society is that we must now consider whether each private action which leaves an electronic trace could embarrass or even ruin us if it becomes public. We are more and more forced to contemplate the obliteration of our private lives. This is the true meaning of the global village which Marshall McLuhan foresaw.

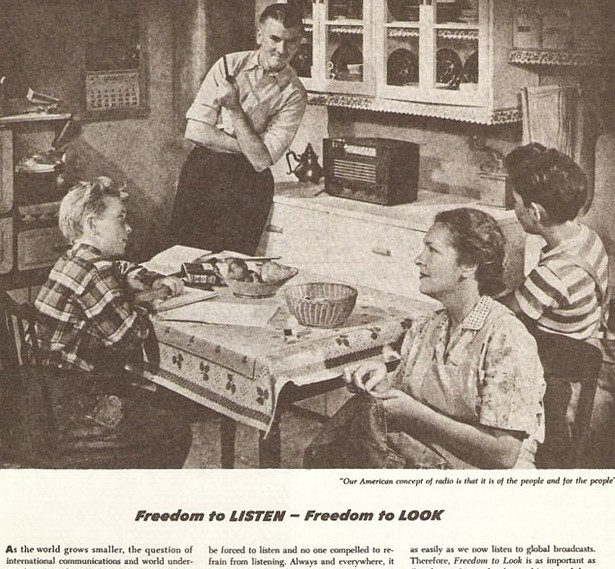

Image: Magazine advertisment for Radio Corporation of America: “Freedom to Listen, Freedom to Look” Family in the kitchen, mother knitting, man smoking pipe, listening to radio, David Sarnoff, UNESCO. Appeared in “The Mechanical Bride” by Marshall McCluhan (1951). Via Wimiedia Commons.