Instead of retreating into urban eco-sanctuaries and buying industrial fare in hygienic and eco-friendly packaging, people need to grow, tend to animals, muck, dig, cook and bake. Only then can we expect people to become ecologically literate and realise that we are part of nature.

After the discovery of ”germs” and their role in disease, humans initiated a war on bacteria for two centuries. It is just the last decades that we start to realize that we are totally dependent on them. There are so many of them inside our body and on our skin that one could almost claim that we are an agglomeration of germs. While we still know that there are the bad ones we should avoid we are also aware of that some dirt is beneficial. Something similar need to happen with efficiency.

The realization that there are fairly hard physical limits to our civilization, sometimes called Planetary Boundaries, has made efficient the buzzword of the day. Of course this is hardly nothing new, scarcity was the rule for most of human existence and efficient use of resources was part of the daily struggle. When fossil fuels were systematically put into our service there followed a period of assumed limitless growth and limitless waste.

For a long period, efficiency was defined mainly in relation to the use of labour and the silver bullet of enterprise was to substitute natural resources with labour. Which meant more use of energy, more use of minerals, water, rocks and sand; more everything – but labour.

Now, there are growing insights that natural resources are not as abundant and limitless as we believed and that there are also limits in the receiving end. We can’t just pump our waste into the natural pools be it the oceans or the atmosphere. It is therefore quite natural, and good, that we look for more efficient ways of using resources. But in my view the solutions are often misguided.

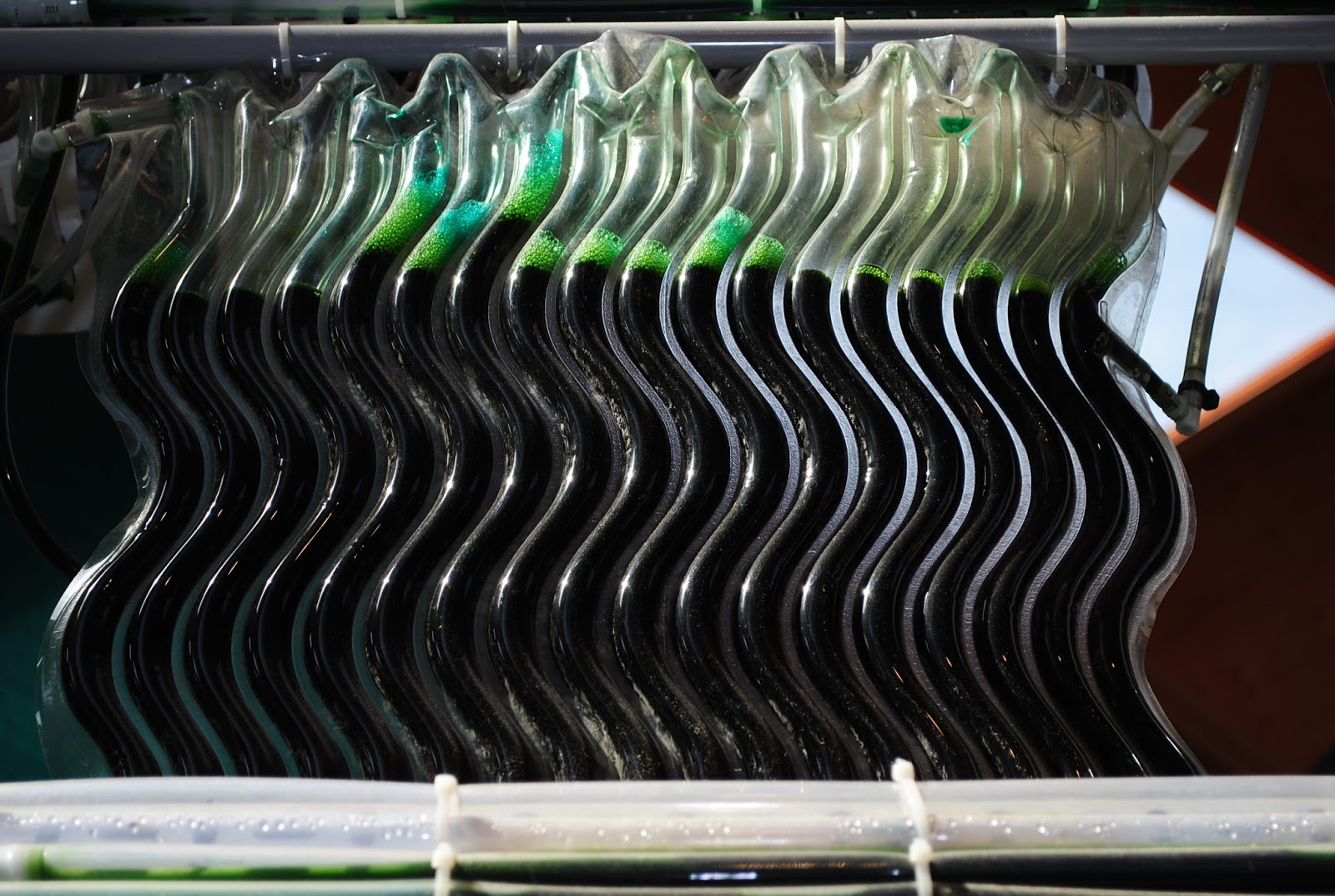

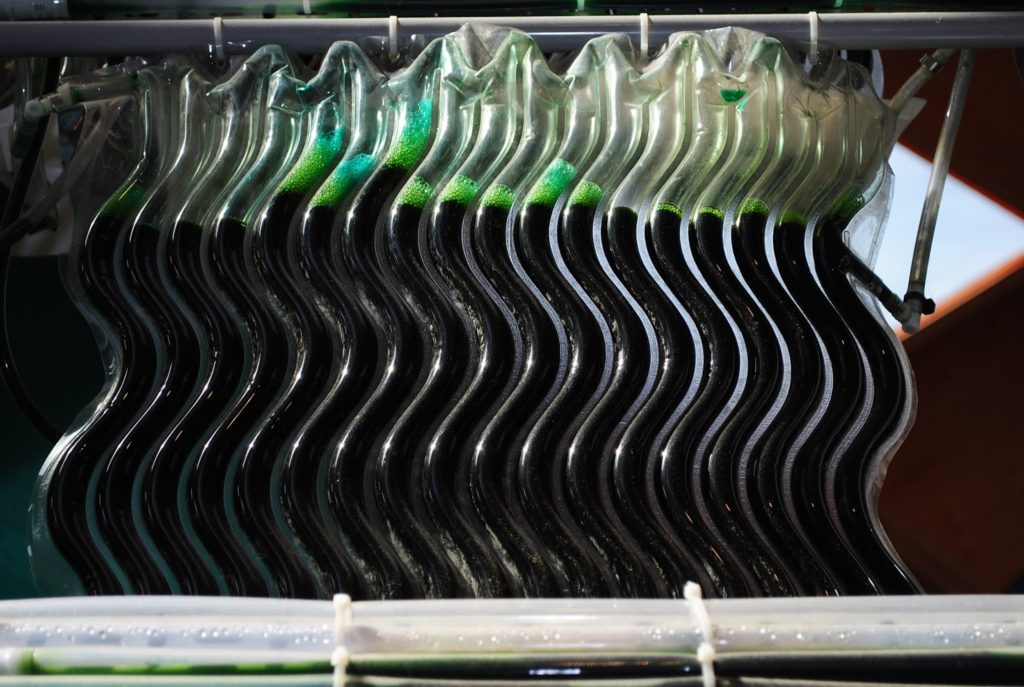

Farming is perhaps the best examples of this. Nowadays we are told that we should grow plants or fish indoor with artificial light to save water and land. And the most used argument in favour of a vegan lifestyle is that there I less need for land to grow plants than to grow animals. Lab meats are said to solve our craving for meat in a better way. Efficient use of land is also a major argument for the use of chemical fertilizers, pesticides and GMOs.

Most urban dwellers have no idea of how food is grown and how animals and plants interact in natural systems and they therefore easily buy into a narrative that goes like this:

“Humans are squeezing out other species, razing the rainforest to feed cattle or for palm oil and cutting down mangroves to grow shrimp. Agriculture destroys the water and the atmosphere, pesticides kills, it even destroys its own foundation, the soil. Most agricultural land is used to feed cattle which also are most harmful for the climate.”

While there is some merit in all this (with the exception for the blame on grazing cattle) the solution which has gained traction is to withdraw humanity into sustainable cities where the food is grown within city walls. In this way we can leave the rest of nature to all the other creatures in God’s garden.

Overall, the alleged efficiency of most of these systems is an illusion because land and resources are mostly used to the same extent as earlier – but somewhere else. See example further down.

What worries me a lot more than the miscalculations, however, is the view of our relationship with nature that is reflected in this narrative. The idea that we can save both ourselves and nature by retracting from nature, limit our interaction with nature to watching Animal Planet and going whale watching or gorilla spotting on eco-touristic trips.

For sure, those creatures need all those nature reserves that we have created and we need to expand those in parts of the world, in particular to coastal areas. But, as with germs I am afraid we draw this too far. Many advocate artificial production systems in a similar way as sterility was promoted as an ideal for hygiene. But distancing people more from germs mostly make them much less able to strike a balanced view on the merits of washing their hands or throwing away leftovers.

In a similar way, I think that instead of withdrawing into urban eco-sanctuaries people need to immerse themselves in nature and dirt. They need to grow, tend to animals, muck, dig, cook and bake rather than buying industrial fare in hygienic eco-friendly packaging. Only then can we expect people to appreciate the real work, the resources needed, the interaction between humans, animals and plants. Only then can we expect people to become ecologically literate and realise that we are part of nature.

The saving resources myth

The most flagrant myth is that vertical indoor farms powered by LED lights saves space. When you point out that they require a lot of energy, you are told that that energy can come from solar panels, fully renewable and benign. We can leave the discussion about exactly how benign solar panels are when it comes to resources. We can also leave the discussion how to store solar energy over the seasons in the Northern parts of the globe, and just focus on the area used. Do indoor farms really save space?

Let’s envision a house with a vertical farm in the basement and let us put solar panels on top of the building. The roof is hit by sunlight with an intensity of some 1000 W per square meter. Our solar panels are very efficient and convert 15 % to electricity that will give us 150 W per square meter. The basement is powered by efficient LED lights. If we want to grow lettuce we will need about 250 W per square meter for 12 hours per day. Assuming very small losses in transmission and for the light we can grow 0.6 square meters of lettuce for each square meter of roof area. Each layer of plants in the vertical farm thus needs a much bigger area of solar panels to produce the electricity needed. And this is only growing lettuce. If we were to grow tomatoes, grain, potatoes or cabbage we would need much higher light intensity.

These calculations are in reality extremely optimistic. Of course, in the winter where I live there is almost no solar energy produced at all. To produce food in winter we would need solar panel areas perhaps 25 times as big as each layer in our indoor farm! So for a farm with 10 layers we would need 250 times the area somewhere else, outside of the sustainable city’s walls.

These are back-of-the-envelope calculations, an art which seems long forgotten. You can read more here.