Meeting the Paris Agreement’s aspirational target of limiting global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels could “substantially” reduce the risk of sea ice-free summers in the Arctic, research shows.

Two new studies find that, under 1.5C of warming, Arctic waters could experience ice-free summers around 2.5% of the time, or one in every 40 years. Under 2C, ice-free conditions could occur 19-34% of the time – or once every three to five years.

However, limiting warming to 1.5C will likely be not enough to prevent ice-free summers from occurring altogether, the researchers note.

Such dramatic loss of sea ice could drive further increases in warming and result in habitat loss for a wide range of species, including polar bears, seals and walruses, one of the authors tells Carbon Brief.

Out in the cold

The new studies, which are both published in Nature Climate Change, focus in on how efforts to curb climate change could affect summer sea ice cover in the Arctic.

After reaching its annual peak extent at the end of winter, Arctic sea ice contracts as temperatures rise through spring and summer. Sea ice then hits its yearly minimum sometime in September or early October.

Since the satellite record began in 1979, summer sea ice cover has fallen by around 13% per decade, with rising temperatures playing a large role in the decline.

With this trend expected to continue as global temperatures rise further, scientists have turned their attention to when Arctic summers could become “ice free”. The term refers to a sea ice extent of less than one million square kilometres, rather than no ice cover at all.

The new research finds that limiting warming to 1.5C rather than 2C could “substantially” reduce the risk of ice-free conditions in the coming decades, says Prof Michael Sigmond, a research scientist at the Canadian Centre for Climate Modelling and Analysis at Environment Canada and lead author of one of the new studies. He tells Carbon Brief:

“We found that under 1.5C, only one in every 40 summers is expected to be ice free in the Arctic, whereas under 2C, one in every five summers is expected to be ice free.”

A similar result was also obtained by Prof Alexandra Jahn, a climate modelling scientist from the University of Colorado Boulder and author of the second study. She tells Carbon Brief:

“I was surprised that half a degree of warming would make such a big difference. The probability of seeing any month-long ice-free conditions are strongly reduced if warming is limited to 1.5C.”

Both studies use modelling to assess the risk of an ice-free summer under a range of possible future scenarios.

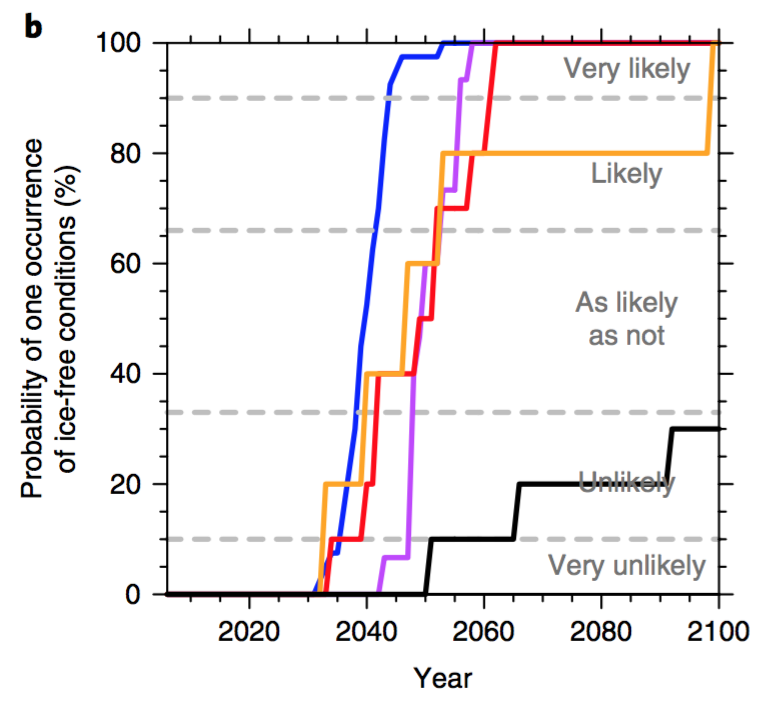

Jahn’s research uses the results from one climate model to to assess the impact of different emission scenarios on Arctic summer sea ice. The results are shown on the chart below, where the probability of an ice-free Arctic summer from 2020-2100 is estimated for each scenario.

These include a “business as usual” or high emissions scenario (RCP8.5; blue), an intermediate emissions scenario (RCP4.5; purple), a scenario where warming is limited to 2C (red), a scenario where warming is limited to 1.5C (black) and a scenario where warming is limited to 1.5C but with a temporary temperature overshoot (orange).

The probability of an ice-free Arctic summer from 2020-2100 under a range of future scenarios including 1.5C (black), 1.5C with temperature overshoot (orange), 2C (red), moderate emissions (RCP4.5; purple) and “business as usual” emissions (RCP8.5; blue). Source: Jahn. (2018)

The results suggest that, under a business-as-usual scenario, the Arctic is likely to experience an ice-free summer every year from around mid-century onwards, Jahn says.

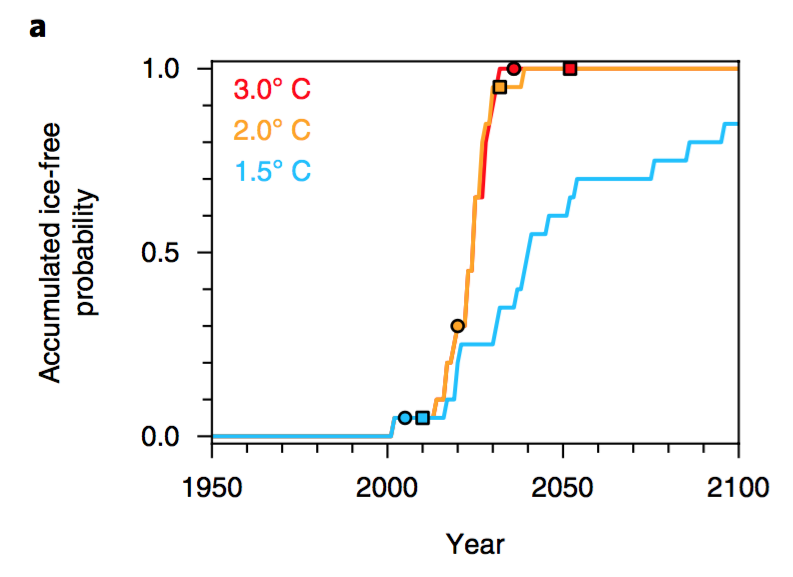

The second study uses a different climate model to simulate Arctic summer ice cover under a range of scenarios.

However, this research focuses on three scenarios where global temperatures become stable at 1.5C, 2C and 3C. Assessing stabilised temperatures – rather the point at which the limits are first reached – gives a clearer understanding of how mitigation could affect sea ice, Sigmond says:

“An important finding of our study is that the probability of ever reaching ice-free conditions continues to evolve after temperature stabilisation. Warming stabilization simulations are thus needed to properly assess the benefits of the Paris Agreement for Arctic sea ice.”

The results are shown on the chart below, where ice-free probability is shown from present day until 2100 for each scenario, including 1.5C (blue), 2C (orange) and 3C (red). The ice-free probability is defined as the proportion of model simulations that reach ice-free conditions in each year.

The lines are cumulative, so they keep going up until all the simulations produce an ice-free summer, or until 2100 is reached. So, for example, under 2C or 3C, all models see an ice-free summer before 2040, whereas under 1.5C, only around 80% do by 2100.

The probability of an ice-free Arctic summer from present day to 2100 under warming of 1.5C (blue), 2C (orange) and 3C (red). Circles correspond to years when the warming threshold is first exceeded and squares correspond to years when the global mean temperature has stabilised. Source: Sigmond et al. (2018)

The results suggest that the projected frequency of ice-free conditions at 2C of warming is around eight times higher than 1.5C.

And, if the world were to warm by 3C, the Arctic could experience an ice-free summer more often than every other year by the end of the century.

Growing loss

Both studies find that, even if warming is limited to 1.5C, the risk of an ice-free Arctic is likely to grow larger over time.

This is because in addition to the long-term downward trend, there is also year-to-year natural variability in Arctic sea ice cover, explains Prof James Screen, a climate scientist from the University of Exeter who published a Nature News & Views article to accompany the new research.

He explains that, as time goes on, the chances of an episode of natural climate variability that leads to extremely low sea ice gets higher and higher. This, in turn, increases the probability of an ice-free Arctic, he writes:

“Consider the analogy of the probability of rolling a six with a standard six-sided die. For each roll of the die, the chance of rolling a six is 1-in-6 (17%) and the chance of not rolling a six is 5-in-6 (83%).

“The more rolls of the die, the greater the chance of rolling a six at least once…There is a 30% chance of rolling a six at least once in two throws and a 60% chance in five throws. By twenty-five throws, the odds of rolling a six at least once are 99%.”

Paying the price

Ice-free summers could cause trouble for a range of wildlife, as well as people living and work in the Arctic region, Sigmond says:

“Loss of habitat directly impacts polar bears, seals and walruses, which use the ice for foraging, reproduction and resting, and for also for people who use ice for hunting, travel and other activities.”

The disappearance of sea ice could also contribute to global warming by causing more heat to be absorbed by the ocean rather than reflected back into space by ice, he says:

“Ice loss also increases warming and can influence ocean circulation and weather – all of which can have impacts on people and ecosystems outside of the Arctic.”

The two new studies add to the growing consensus that achieving the Paris target of 1.5C could “substantially” reduce the risk of ice-free summers, Screen says:

“There is therefore agreement across climate models that the probability of an ice-free Arctic in September would be substantially reduced by achieving the 1.5C target of the Paris Agreement.”

Both studies make an “important contribution” to our understanding of how climate change is likely to affect Arctic sea ice, says Dr Amber Leeson, a lecturer in glaciology and environmental data science from the University of Lancaster, who was not involved in the research. She tells Carbon Brief:

“Each study uses a different climate model to come up with broadly the same conclusions – that if warming at 2C above pre-industrial temperatures is reached, and sustained, then we are locked in to an ice-free Arctic at least once before the end of the century.”

However, each study bases its results on a single climate model and so cannot account for potential differences between models, she says:

“Given the importance of these findings for climate change policy however, repeating this work in the context of a multi-model analysis – for example CMIP6 – is now a pressing concern.”

Jahn, A. (2018) Reduce probability of ice-free summers for 1.5C compared to 2C warming, Nature Climate Change, http://nature.com/articles/doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0127-8

Sigmond, M. et al. (2018) Ice-free Arctic projections under the Paris Agreement, Nature Climate Change, http://nature.com/articles/doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0124-y