Henry David Thoreau lived 200 years ago, but his influence continues, inspiring the likes of Tolstoy, Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., E.F. Schumacher, Wendell Berry, and Bill McKibben, to name an illustrious few.

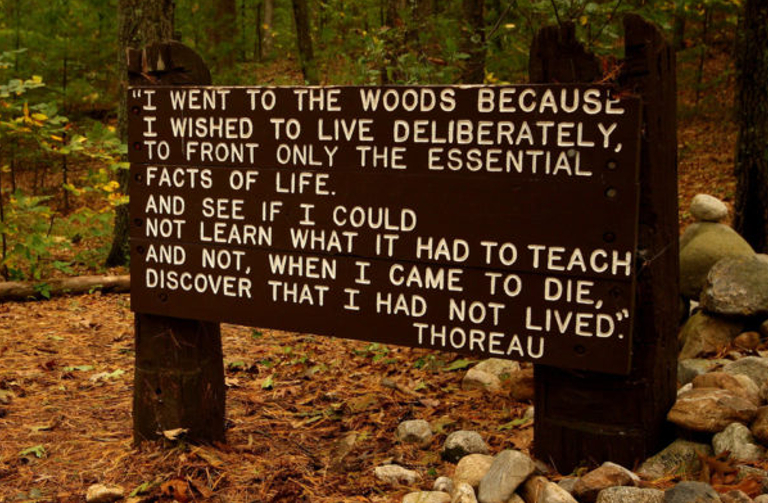

Thoreau’s Walden set the bar of thinking and doing so poetically high and yet so pragmatically down to earth that it just may be that no one will ever again get over it or under it quite as eloquently and profoundly:

“Our inventions are wont to be pretty toys, which distract our attention from serious things. They are but improved means to an unimproved end.”

“A man is rich in proportion to the number of things which he can afford to let alone.”

“There are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil to one who is striking at the root, and it may be that he who bestows the largest amount of time and money on the needy is doing the most by his mode of life to produce that misery which he strives in vain to relieve.”

We are still figuring out, today, the relationship between means and ends, between economy and culture. The dissonance between how we make money and whether it is possible to give back enough to redress the ills inherent in the way we made that money is, still, the crux of the matter.

The modern economy has created 2,043 billionaires with a combined net worth of almost $8 trillion (up 18% in 2016); the wealthiest 1% of the world’s population owns more than everyone else combined; almost three billion people around the world have come to own smart phones in a little more than a decade; 86,000 private foundations in the U.S. have over $700 billion in assets; and yet this very same momentum of wealth creation and consumerism prevents us from responding adequately to the most fundamental crises of our time.

Thoreau’s wildly prescient words in Civil Disobedience still ring true for anyone concerned about how, despite best intentions, our money finds its way to distant activities in which we do not believe:

I do not care to trace the course of my dollar, if I could, till it buys a man or a musket to shoot one with—the dollar is innocent—but I am concerned to trace the effects of my allegiance […]

I quarrel not with far-off foes, but with those who, near at home, cooperate with, and do the bidding of, those far away, and without whom the latter would be harmless […]

It is truly enough said that a corporation has no conscience; but a corporation of conscientious men is a corporation with a conscience. Law never made men a whit more just; and, by means of their respect for it, even the well-disposed are daily made the agents of injustice. A common and natural result of an undue respect for law is, that you may see a file of soldiers, colonel, captain, corporal, privates, powder-monkeys, and all, marching in admirable order over hill and dale to wars, against their wills, ay, against their common sense and consciences, which makes it very steep marching indeed, and produces a palpitation of the heart. They have no doubt that it is a damnable business in which they are concerned; they are all peaceably inclined.

Where Thoreau refers to law, I hear markets. (Reread the preceding paragraph making that substitution.)

So, I believe that the most conscientious thing I can do is bring some of my money closer to home, shortening the distance between me and that which my money supports, lessening my complicity in distant ills and increasing my connection to things that I can support directly.

In times of war, we’ve always had conscientious objectors. In times of economic and political befuddlement, can we encourage a corps of conscientious investors? It’s a bit risky bringing up conscientious objecting, here, as it suggests that only peaceniks should mobilize to invest in local food systems. I’m taking the risk of that confusion because there is something in the concept of conscientious investing that is worth reflecting upon.

Objecting and protesting are, of course, cornerstones of democracy. Perhaps we need to rethink investing in a similar light. We tend to see investing as something to be done in private, looking inward, all about personal gain. We tend not to see it as a way of protesting or supporting, but, rather, purely as a numbers game. What if we looked at investing the same way we look at protesting? As a cornerstone of democracy? As a way for us to take a stand? As a way for us to connect with others around shared concerns, looking outward, focusing on societal health?

Now, I’m not talking about turning the entire conventional idea of investing on its head. (Kind of like turning the word soil on its head… but I get ahead of myself. More on that later.) Or, should we say, I am talking about turning the idea of investing on its head—but only for a few minutes a day, so that blood can flow in a different direction.

“We need economists and climatologists and marine biologists and hydrologists and politicians and geologists and industrialists and environmentalists all at the same table,” said a speaker at a recent renewable energy conference. “We need to think in terms of whole systems. We need multi-sectoral, interdisciplinary solutions.”

While she spoke, I thought of conference upon conference, report upon report, scientific study upon economic model, flow chart upon org chart, yards of elaborate graphic facilitations taped up on workshop walls, feedback loop upon feedback loop, certification upon certification, corporate disclosure upon corporate disclosure, policy upon policy, regulation upon regulation.

And then I thought about making a loan to a local organic farmer.