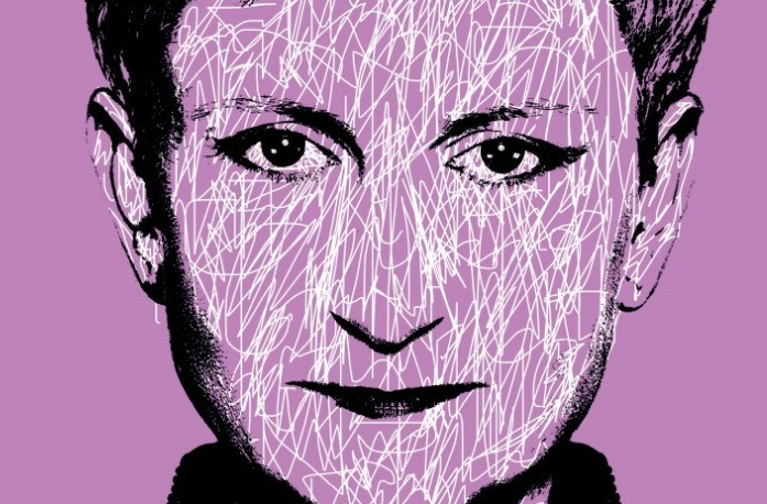

If it is true that we are living through a time in which our collective imagination is increasingly devalued and undernourished, what might be the role of story in that, and how might story be part of the remedy? There are few better people to discuss this with than Sarah Woods. Sarah is a writer across all media and her work has been produced by many companies including the RSC, Hampstead and the BBC.

Her opera ‘Wake’, composed by Giorgio Battistelli, opens in March, as does her play ‘Primary’, about the UK state education system. Alongside many other projects, she is currently writing the musical of the play she co-wrote with the late Heathcote Williams ‘The Ruff Tuff Cream Puff Estate Agency’, about squatting and DIY culture. Her play ‘Borderland’ just won the Tinniswood Award for best radio drama script of 2017.

Sarah is a Wales Green Hero, and her work is about, as she told me, “story wherever it’s most useful, across the board”. I started by asking her the question I always ask in these interviews, but never as the first question. If you had been elected as the Prime Minister at the next election and you had run on a programme of ‘Make Britain Imaginative Again’, what might be some of the things that you would announce in your first 100 days?

I would want for everybody to start looking at society and their lives as systems, which is about three things isn’t it? Elements and interconnections and then the things that come out of that. I suppose at the moment I feel that we’ve got a problem with the way that we’re relating to each other. There’s a lot of division so that we’re in little boxes.

We’re not able to see outside of those little boxes very often, and actually those interconnections between us are the ways in which we start to engage our imaginations beyond ourselves, and start to see things more systemically rather than as single issues. Single issues aren’t really going to solve the problem.

I would use systems theory, which is essentially about using our imaginations because it’s relational, to start to resolve a lot of the problems that we’ve got. In doing that obviously I would use story to do that. I would use story and I guess in a lot of the work I do I look at systems theory and story and how they’re sort of the same thing. Stories are little systems.

So how would you evaluate the state of health of our collective imagination in 2018?

Well, it’s interesting. I guess there’s a number of things happening on different strata. There are really serious dominant narratives that we’ve bought into. We’ve bought into them for a number of reasons, not least because we’ve been reducing and reducing the sorts of ways we tell story.

If you look at what’s been happening on television and in film, there was all this idea of, you know, ‘there are only eight stories in the world’, ‘there are only three stories in the world’, maybe there’s only one story… We’ve gone down this very reductive pathway, which is partly to do with capitalism trying to turn things into commodities and find the answers to making money out of things.

Story has really suffered. You know how things hop across, like viruses do. If you look at what’s happened in film and television, although we’re starting to move out of that a little bit now, you could say that’s also affected our media in lots of ways. Alongside that we’ve had an explosion of the sorts of ways in which we receive information. One of the effects that’s had, one of the negative effects, is that it’s made us focus perhaps on things more superficially, and not think as deeply as we might, often, and reflectively about things.

Those two things together have meant that we can end up in quite small spaces in terms of not only the stories we’re telling ourselves about who we are, in the world, but the stories that we’re receiving. There’s a whole sort of topography of story, which is about what we carry inside us and what’s coming at us in various ways, from the media, from friends and family, and also from the past and future.

We’re at a turning point now, it feels to me, because lots of people are starting to talk about the story. People talking about story more is an indication that people are wanting to imaginatively engage more. We’re in unhelpful boxes that are dividing us from the possibility of the plurality of story and essentially from each other.

One of the people I interviewed was Mohsin Hamid, who wrote The Reluctant Fundamentalist. He wrote this beautiful piece where he said that writers need “a radical engagement with the future”. I wonder what your thoughts were on that, and what that might look like?

Yeah. I guess I’ve been doing quite a lot about the future in the past number of years. I feel there’s been an inability for us to engage productively, positively, with our future. My kids have grown up, and I imagine yours too, essentially surrounded by dystopias of one kind or another in a lot of the films and literature that they’ve engaged with. They’re pretty sick of it, mine, although I don’t think they fully realise the effect that it’s had on them.

I’ve actively tried to engage people, communities, with the future. What I’ve decided is that the dystopias are something that Paul Mason said, was that it’s not that we keep imagining the end of the world. What we’re rehearsing is the end of neoliberalism. It’s the end of a system that we’re working within, we operate within, and we don’t know what comes next.

I think there is a crisis of what comes next. It is part of my responsibility as an artist to engage with the future and help other people engage with it. A lot of the stuff I do is about the future and is about relationally trying to reconnect people to ideas of the future. Because everybody I talk to, lots and lots of marginalised communities, know that the future isn’t going to be the same as the present is. In really radical ways. But people don’t know how to think about it. There are no places for people to really imagine what that might be like, and to share stories about it, to create those stories.

When I was a kid people talked about the future all the time. Every comic you got was all about the future; all the TV programmes were all about the future. Nobody really talks about the future very much anymore. What happened to the future?

Things have got really, really complex. We’d sort of recreated the world, hadn’t we? Post second world war, certainly in our society, and we had big technological dreams. I feel like neoliberalism has put a stranglehold on the future. It put a stranglehold on women’s equality. Women were like, “We want choices as to whether to go to work” so then neoliberalism said, “Haha well, yes you can have the choice to go to work, and when you go to work we’ll make it so that you can’t stop going to work.” Now you need two people to work.

Then the technology that was meant to set us free in different ways again has become in service to neoliberalism. Because what neoliberalism does is always look for where’s there’s more surplus value, which is essentially, you know, Marx would say in labour really, and obviously in the means of production.

If you see technology as part of the means of production in the widest sense and then us as women, anybody has ways of creating surplus value, then you can see how everything’s channelled into that sort of neoliberal grasp really. We’re in that sort of a stranglehold. Obviously neoliberalism is faltering and in several crises, and has been for quite a long time.

It then becomes very hard for us to see beyond that. The way that economics is talked about, and has been mystified and turned into this strange science that isn’t a science, means that we feel that we don’t know how to understand it, and so we don’t know how to fix things.

Also, it is complex now, isn’t it? We’re in a systemic crisis. Because stories are not told well, and haven’t been told well by probably you and I at times, and certainly by the green movement, we’ve told some of the wrong stories, and that hasn’t helped people to engage with the biggest problems we’ve got.

A lot of the ways we’ve tried to solve things is to make people responsible as individuals. So to say you need to turn your taps off, your lights off, you’ve got to recycle. And a lot of those things can be really, really de-energising and isolating in a world that has become quite isolating. What story can do, and what imagination does, is create the relational connections that can energise us so that we can reach up and start to deal with the biggest problems we have.

You’ve written that stories offer a hugely effective way to catalyse communities to transcend the limits of our world views and rehearse new ways of being. Could you talk a little bit about that? Could you tell us a bit about your work doing story work with communities? Any experiences that stand out, and why does it matter?

I work with this layers of narrative idea. As individuals we all have our entrenched positions on all sorts of things. Things that we might get really upset and defensive about that really matter to us. I suppose I always think it’s important to start from where people are. So with all of my work – I’m doing a community opera at the moment working with 200 people from Birmingham alongside a big orchestra, and soloists – so it’s starting from where those people are.

We started with their stories and that’s where the opera began. With the anti-fracking campaign I did a couple of years ago, where we were looking with a co-operative group to create a grass roots anti-fracking campaign structure of campaigners around the country, we started in those places with those people talking about their concern about their house insurance, with earthquakes and the water quality for their grandchildren.

So you start with those individual stories and then what I do is to create a plurality of story. Get people to tell each other those stories, and to understand that there are a number of different positions, and even opposite positions. If that dialogue is really well held, and whether that’s presented in a drama or whether it’s done as a live event with people present, the idea is that you get people to realise there are a lot of different positions. You start to create a story system, and within that story system, people start to see that there are also then a number of different solutions.

It’s very energising for people to work together and talk together, and from that you can start to create action, and when people are feeling energised and positive, you can also get them to see how it links to the biggest problems that we’ve got. That rough structure I use in lots and lots of different ways. Either to create works of art that I then will write and put on, or to do more live campaigning events. I think it works, and it works because it’s systemic, because it creates a whole for people to feel safe in, but also then to experiment in.

What do you see happen in people when you bring them into a space where their imagination is invoked, or respected, or nurtured?

It’s a deeply human experience, because actually we all tell ourselves stories all the time, and people don’t necessarily realise it, because it’s something we do innately. So we hold stories that we tell ourselves about ourselves, about the people around us, and we tell stories whether it’s on social media, or in real life, about our experiences all the time.

People tend to think that doing something that’s about the imagination is a bit scary and maybe not for them. There can be a little bit of nervousness around it. But if you almost bypass that, and just get people to start telling stories and they find themselves in it, what people realise is that we all belong in that place, and we all know that place.

And yes, I’m working with my imagination every day, so I’ve got really hardwired sense of that in my brain, but it’s there in everybody in all sorts of different little ways. I suppose I work a lot of with values, and values are obviously about people’s emotional response to things as well. What you start to see is greater empathy.

I certainly see people become more open and when you become more open you’re more open to relationships with others. You’re more open to other peoples’ perspectives. There’s often a shifting out of an entrenched point of view into something that’s much more open to change, I suppose. Using your imagination, and if you think of the rules of improvisation which are the freest way of working imaginatively – and again, which we do every day in conversation, most of us – it’s about, within confines, being entirely free.

If you set people’s safe confines, and enable them to be free, it’s a hugely releasing experience. I almost don’t tell people that that’s what we’re doing. We just do it because it is all so innate. If you start to fall in love with someone and you spend time with them, people are playful, and open, and the same as we are often with our kids, as long as they’re not winding us up. But it’s there in all of us. It’s deeply human and deeply natural. By giving it names sometimes we estrange people from it.

As a creative person yourself, how do you sustain that? What’s your process? Are there times when it feels embattled, or under pressure, or is it just an endless spring of inspiration and flow?

It’s a fairly endless spring I would say. I only do things I really, really believe in. My little sort of Pollyanna style mantra is, “Is this the most useful thing I can do?” If I say, “Yes it is” then I do it and I know I’m doing what’s useful.

I know if I’m not doing things that I feel are useful, that’s where I start to have some existential crisis fairly quickly. So as long as I stay really true to my values, what excites and inspires and energises me is then relationships with other people and with ideas, obviously. I just keep making myself go out into the world. I also take on projects that are massively challenging. Stupidly challenging.

I find that helps energise me, for the most part. And, you know, if you’ve got strong collaborators, you know someone’s always got your back. I’m part of the New Weather Institute, and Andrew Simms and I absolutely hold each other’s back and make sure the other’s okay. Having somebody there who you know is looking after you, and who also knows you, deeply creatively, then that’s always a great thing.

There’s a lot of talk right now about the impacts of digital technologies on attention. How do you see the impact of those technologies in the work that you do?

Interesting isn’t it? There is a tendency for people not to give themselves the space to think deeply, and reflectively, as much perhaps. I see that a bit in my kids to a degree. I feel like people recognise a good story. I feel in the stories that I’ve told, I don’t find it difficult to engage with people.

But I feel I need to be absolutely clear about making big efforts to make the journey to people and not expecting people to come to me. Maybe that’s the difference. Maybe we used to expect that we would set up our great stories and people would come to them. Now I certainly feel I’ve got to do the work of going out to people and really strongly engaging with them. And using all the same old things to do that: comedy, disruption, shifting people out of entrenched positions and positions of comfort.

People want to be engaged, and in all the work that I do – whether it’s with homeless people, refugees, Sikh women who meet to knit things – whoever those people are, they all understand, deeply, that we’re in a crisis and we need to do something about it. My experience has been that if you go and genuinely open heartedly engage with people, people have a huge amount to say on all of that.

It’s really encouraging what people do say. It’s just that often people feel disregarded, and separated, and isolated, and that what they have to say isn’t particularly of interest. People are ready to be engaged actually, it’s just about how we do it.

If in our public lives we’ve run out of, or we don’t encounter, many stories about the future as positive thing, if we want to start engaging people in stories about the future as something really desirable and wonderful, and trying to overturn those dystopias, how do we do that? How do we create those hooks?

It’s tricky. I do a lot of work for BBC Radio and always when you’re selling a story, they want to know what’s at stake, what’s the conflict? So dystopias actually, in story terms, work really, really well. Stories of difficulty and conflict and disaster are much, much more easy to tell in that sort of American film story structure that has really become quite dominant over here, alongside soap operas and stuff that thrive on conflict and difficulty. It’s really, really hard.

I’ve found it really, really hard to tell positive stories, in the same way that that newscaster messed up his career by talking about having more good news on the news. He now works for Positive News actually, and it’s really, really difficult to do that. I mean I find ways of doing it, but that’s the challenge. It’s not that people don’t want positive visions of the future, and not that they’re not ready to engage with those visions, but our story forms don’t really work in our favour to do that.

What other elements of a good story? Huge question.

I do bang on about systems a lot. The way I teach playwriting and story is encouraging people to think about a system. A good story has in it characters, structure, story plot. It has those basic elements and really, how you create a story is how you interconnect those things. They’re all connected to each other really, really strongly and the better connected they are, the more satisfying the story is.

You define your set of ingredients and then you work with it. You don’t bring in too many extra things from outside. Systems are a great way to understand how we live and a great way to tell stories, and there’s a lot to be learnt from that way of thinking. That’s how I teach them and that’s what makes a good story, is something that’s deeply and well connected.

You talk about different narrative levels, of super-narrative, and personal, and communal. Can you just talk a little bit about that?

Essentially we have all these really big stories that we try to engage people with, but they’re distant from us perhaps in space and time. We’ve got more pressing things in our lives. It’s very hard to make that sort of stuff stick unless you can connect it to people’s lives and to where people are.

So, start from the individual, start from the personal, and look at what are our connections, as individuals and communities, to those bigger picture? Then as a group of people, how can we connect with it and actually take action? That works really well, because people do want to create change, but these things are so massive that they disable us continually, don’t they?

Even as creatives and campaigners working with all that stuff, it is disabling. I’ve found there’s times when I’ve moved away from working on climate change a bit, and then back into again, because it’s just felt too exhausting. We all experience that. So yeah, finding ways to engage individuals with that bigger story, or any of those big stories, is the only way to genuinely energise and create action. It’s the same thing.

It’s the idea of systemically linking one thing to another. I’ve done that over the course of an evening, or you can do that in longer projects with people, and it’s a good way of maintaining energy and ensuring people feel well connected to each other. All of these things, all of it, is about how do we as individuals create relationships between ourselves and between important ideas in the world that are sustainable? I guess for me that’s what it all comes back to, and our imaginations are a really, really key part of that.

Any last thoughts on imagination that I haven’t asked you the right question to get you going on?

I’ve probably said most of my usual stuff, and I suppose the only thing just to reiterate is that… I did this piece called My Last Car, which was talking to people about all their favourite things that had happened to them in their cars, with the idea that maybe the car they had now was their last car and they wouldn’t have another car. We did piles of interviews with people. A lot of them we did at Coventry Transport museum. So talking to car enthusiasts, people whose lives were their car, and I said to everybody at the end of the interview, “Do you think in another ten years you’ll still be driving around in the same ways as you are now, in your car?” And they said, “No. No, no, I won’t.” And I said, “So what will you be doing instead?” And they said, “I don’t know.” So people understand that we’re at a point of change, and would like to imaginatively engage with what comes next, but at the moment there’s a real disconnect. I see a lot of my job as trying to build those connections, and we just need lots of us to do it, so that people get used to making that journey. It’s a little bit like when you’re training a dog. Not that I’m saying the general population of the country are like dogs, but you know, in the way that you’ve got to do the same thing over and over again. We all have to do that, don’t we, to develop new habits? I suppose I see it as trying to create a new habit and that we just have to keep doing it over and over again.

Like building new neural pathways.

Exactly, the little sheep trotting across a field sort of thing.

So it’s like creating what if spaces, those kinds of spaces where people can ask, “What if this was your last car?” So really what we need to be doing is design as many of those into daily life, in as many unexpected or expected places as possible, just to start training those kind of pathways?

Yeah. I guess what I’ve done to achieve that, which I think works – which you’ve done in different ways with all your work – is to catalyse people. Start from where people are and catalyse them. Then you move them into a more open space and then, yes, actually to get people to create that stuff themselves, because we tend to go around telling people about stuff.

Saying, “Look there’s a crisis, we’re going to tell you about it.” Rather than saying actually, “We know you know where’s a crisis, and what we need to do now is find spaces where we can come together and really explore what the stories are that are going to enable us to deal with it.” So absolutely sharing the means of production and getting out there, and having ‘imaginariums’.