This week we continue our Dark Kitchen exploration of food and eating in times of collapse. For our final course this month, food campaigners Olga Bloemen and Bella Crowe tell the story of how a cafe and two refugee Syrian cooks brought warmth and imagination (and falafels) to a small market town in Aberdeenshire.

There is a story about a soup made of stones that is told in many languages across Europe. In all versions, one or more travellers – tramps, pilgrims, monks or soldiers – arrive in a strange village, hungry, only equipped with an empty soup pot. They ask locals for some food to share but everyone refuses: they barely have enough to feed themselves, they say, their food stores are running empty. Disappointed, the travellers go to the stream, fill their pot with water, put a stone in it and place it over a fire.

One of the villagers can’t resist and ventures out of her house to ask what they are cooking up. We are making the famous and delicious ‘Stone Soup’, the travellers say, if only we had a little more veg, that would make it taste even better! The villager doesn’t mind parting with some of her carrots which are added to the pot. Another villager comes by, curious, and is told about the Stone Soup. If only this soup had a bit of seasoning, the travellers lament, and, of course, the villager brings them some. And so it goes on, with each villager who passes, enticed by the delicious smell and rumours of a feast, adding more ingredients. Then, the travellers (secretly) take out the stone and the hearty soup is shared by everyone, during a feast that lasts long into the night.

Food speaks to us, to our hearts and our guts. Food can reel us into a distant past or conjure up a person or place in our minds. Food can be artwork, crunchy salads bursting with colour and texture, hot soups with such intricate blends of flavours. And we speak through food. Cooking a special meal might be a message of love for friends or family. But what about at a societal level, what are we saying? When the response to poverty is food banks; when cauliflowers are more expensive than doughnuts, when companies advertise unhealthy food to children who grow up addicted to sugar, when farmers are paid less for their milk than it costs to produce it, are we valuing the bodies, lives and dignity of people?

Hayat Shahoud and her family fled from their home in Homs, Syria and spent five years in refugee camps in Turkey before being ‘resettled’ in Aberdeenshire, Scotland. One of the few things Hayat managed to bring with her is her stainless steel falafel press – even, finally, across the UK border controls. Wherever they were, the shape of the falafels that fed them was exactly like at home.

When you don’t speak the language of a place, food speaks even more loudly. We can only imagine what messages Hayat and her family received when they arrived in Scotland, a place where not many folk would think of kitchen utensils as prized possessions, where Mars bars are fried instead of falafels. A nation afflicted by diet-related ill health, where growing and preparing food are not inscribed into modern life.

Still, there are other food stories which are being told, more quietly, of hospitality and conviviality. In projects across the UK, people are growing, preparing and sharing food together. In this time marked by unpalatable narratives of us and them and who deserves to be where, food can create a common ground on which to meet. In Granton, Edinburgh, neighbours have begun to dug up the street corners to create growing spaces and Scottish, Nepali and Kenyan families, as well as others, are now sharing skills and crops and stories. Granton’s home-grown kale is turned into irresistible pakoras at their weekly community meals, and last year they harvested their first quinoa crop. In Glasgow, the High Rise Bakers meet twice a week in a borrowed kitchen in one of the local flat blocks to make nutritious, affordable bread for the community. The bakers, many of whom are refugees and migrants, enjoy Tanzanian chai breaks with cardamom, cinnamon and ginger tea while waiting for the loaves to rise.

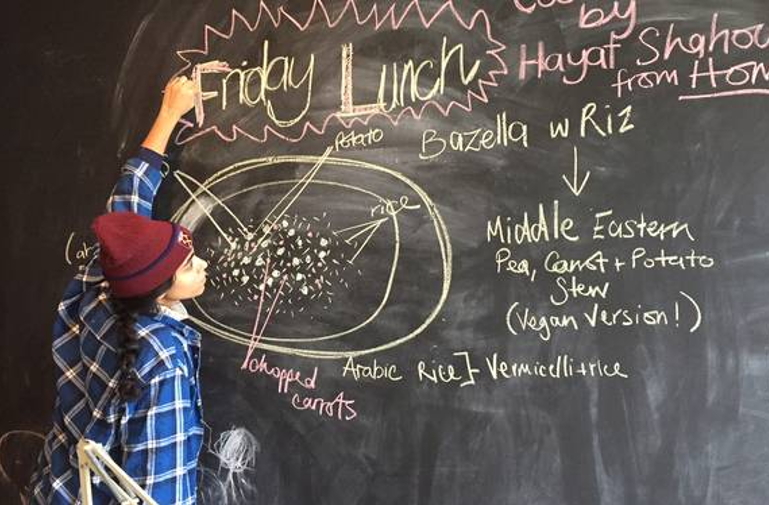

As for Hayat, together with Abeer Alhalabe (another Syrian woman new to Scotland) she now helps run No. 11: a community café in Huntly, a small, rural market town. Not many months ago, No. 11 Gordon Street was an empty shop on Huntly’s high street, now it is a home for the slow and messy work of building relationships, an initiative of Deveron Projects, which connects artists, communities and place in Huntly.

No. 11 was started as a pilot project by Marc Higgins and Aya Haidar – a British anthropologist and a Lebanese-British artist, who wanted to create a place where people are valued for the different skills and experiences they bring. The doors opened in November 2017, and since then many hot and tasty meals have served to bridge the language barrier.

It’s a brisk January Friday, and they’ve got a lunchtime event happening. Project volunteers drop off bowls, tablecloths, and chairs taken from their own houses, kids are crawling over the floor, the chatter is rumbling contentedly over cups of tea. Hayat brings in a great pot of steaming Syrian vegetable stew and rice. After she explains with few words and gestures that in Syria, people eat with their hands, people start dunking warm flatbreads in olive oil and za’tar – a delicious nutty green herb blend, combining thyme, sesame seeds, and salt. Fingers deftly scoop up the hearty flavours, so familiar to Hayat, but new to others in the room. She proudly watches while everyone digs into the food and encourages late-comers to help themselves too: ‘Eat, eat!’. We sit and talk around big tables; the food is by donation.

At No. 11, it is Syrians who are hosting the Huntly locals. Rather than be bound by the expectation of gratitude and demure behaviour, Hayat and Abeer can bring their creativity and energy, and tell their own story. They can practise their English, while locals strike up some Arabic, aided by Google Translate on their phones. And the café is a welcome addition to Huntly’s high street, which was lacking low-threshold community spaces.

Originally, Marc and Aya thought about calling it ‘Al-Nofara’ – ‘The Fountain’ in Arabic, after the oldest café in Damascus, but realised that this may exoticise the place and alienate some locals. They also don’t shout about the cuisine being Syrian, but hope that No. 11 allows Scottish people to understand from direct experience all there is to gain from refugees who are contributing their lives, skills, ideas, smiles, and culture to this country. Food is a necessity and it entices people in who wouldn’t normally get involved in ‘integration schemes’. Something different can happen when sharing a meal with others, and experiencing new flavours that taste of different lands. It is a living invitation to remember that the world beyond what is known is full of treasures and that difference can be full of wonder rather than fear.

With the growing season starting, No. 11 is looking to link up more with Deveron’s ‘The Town is the Garden’ project that encourages people to grow their own food in their gardens, allotments and public places. In this time of transience and virtual realities, it is not only refugees and migrants who have been uprooted, and even those born and bred in a town might struggle to feel a sense of belonging. Just as sharing food can help us see each other in new ways, putting hands in the soil can bring new perspectives to the place we live. Digging up street corners with neighbours, feeling gratitude for rain and sunshine on behalf of the plants, or excitement about worms and bees: we live beyond ourselves when we start growing food. While our physical surroundings, in turn, become part of our bodies.

Yet, however powerfully growing, preparing or sharing food together may speak to us and through us, these projects have an enemy lurking, fostered by negative headlines and sly politicians. It is the scarcity narrative: ‘there is not enough’. In times of imposed austerity, it breeds fear for the loss of support and demands gratitude for meagre provisions.

While this narrative looms over poor communities, telling its urgent tale of the need for frugal accountancy, the rich in society dine still more extravagantly. It is inequality that is endemic, not scarcity: here in Scotland, there are many more empty homes than homeless people – more than 37,000 were left vacant in 2017. Yet the dominant narrative. drowns out the solid facts, and the pushback is weak.

It is this mixed-up context that makes spaces like No. 11 essential, but also means that most of the people who are dropping in are Huntly’s more affluent residents, who don’t feel any threat to their vital support. It is easy to connect over plenty. In contrast, Ruth Lamb from Govan Community Project in Glasgow (who gave a presentation during the Friday lunch) described how it is their food distribution service which brought ‘locals’ and ‘new Scots’ into the same room. People are thrown together by the common and stressful experience of scarcity. While collectively we do have enough and everyone could experience abundance; across Scotland, there are kitchens with empty cupboards, and people who do not have a kitchen at all. With mouths to feed and no money to do it with, projects like this one in Govan are providing essential basic nourishment. But in the desperate space of hunger, and under the weight of stigma, there is little room for warm conversation or curiosity.

Despite its neat outward appearance, Huntly is a town where many people are struggling, poverty is rife and the austerity agenda has debilitated public services. People are enduring benefit cuts and waking each morning with a fresh struggle, another form to fill in, another ultimatum. The stakes are high, with hunger and homelessness constants on the horizon. This demolishing of public support for people in poverty can create bitterness towards newcomers, with the thin allocation of resources stretched over ever more human beings.

Last year, Inverurie, the nearby town where most of the refugees in Aberdeenshire are resettled, was hit by floods. As water gushed through the fields and the streets, people were forced to leave their houses. The culprits for this destruction are many: from climate change, to poor rural planning, yet it was refugees who received some of the fury. There was a vocal backlash against the council for providing housing to refugees when so many local people were struggling.

However just as in the story there always was enough to go around, and there is more than enough today. Yet our wealth is disastrously distributed and our narratives close doors. Many of us have forgotten how to host – or be hosted. The art of connecting with people we do not know is getting lost in ‘meals for one’. Individuals face real, hard scarcity while society shivers in a false perception of it. Perhaps, one piece of the puzzle are projects like No. 11 that work a bit like the Soup Stone, that create – as if by magic – shared spaces and a sense of abundance. Places where people, wherever they come from, can bring skills, stories and resources, where the community is much more than the sum of its parts.

However just as in the story there always was enough to go around, and there is more than enough today. Yet our wealth is disastrously distributed and our narratives close doors. Many of us have forgotten how to host – or be hosted. The art of connecting with people we do not know is getting lost in ‘meals for one’. Individuals face real, hard scarcity while society shivers in a false perception of it. Perhaps, one piece of the puzzle are projects like No. 11 that work a bit like the Soup Stone, that create – as if by magic – shared spaces and a sense of abundance. Places where people, wherever they come from, can bring skills, stories and resources, where the community is much more than the sum of its parts.

Hayat’s Falafel Recipe

INGREDIENTS

1 kilo of dried chickpeas, soaked overnight in plenty of cold water

1 large onion

5 cloves of garlic

1 tbsp of cumin

Pinch of chilli flakes

Sunflower oil for deep-frying

Makes enough to feed Hayat’s husband and three (hungry) boys.

Drain the chickpeas well and add to food processor/or mincer together with the onion (roughly chopped), garlic and spices. Blitz into rough paste and move to a bowl. Leave for an hour or two out of the fridge. Heat oil in a pan until hot enough (about 180C). If you don’t have a falafel scoop, use wet hands to shape a palmful of the mix into a ball and the flatten slightly. Drop carefully into the oil – if they disintegrate, add a bit of gram flour to the mix. They’ll be ready in about 3 minutes. They should be a dark, golden brown – the colour of falafel is known as baked bread.

Serve with warm flatbread, hummous or tahini, and sliced tomato and chopped parsley.

—

Next course:

This is the last course in our Dark Kitchen February feast. Dark Kitchen will continue as an occasional series when the new-look Dark Mountain website is launched in April. If you would like to contribute in the future, do get in touch with a short description of your piece to series editor Charlotte Du Cann ([email protected]) Thanks all and bon appetit!

Images: Aya writes up the menu on No.11’s blackboard; drawing from ‘Walking without Walls’; open space at No 11 (all from Deveron Projects); outside window of No.11 (photo; Joss Allen)