One swallow doesn’t make a spring, and nor does one scientific paper change a whole body of evidence. But you could be mistaken for thinking so after the poor media coverage last week of a new piece of climate research.

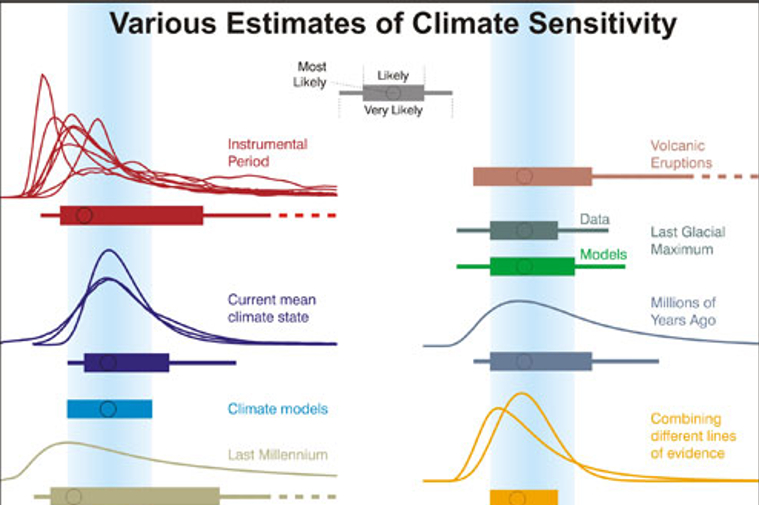

A study published last week in Nature (“Emergent constraint on equilibrium climate sensitivity from global temperature variability”) claims to tighten the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), range for (short-term) Estimated Climate Sensitivity (ECS), the amount of warming to be expected from a doubling of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere.

The study puts its best guess at 2.8C, which is pretty squarely in the middle of what scientists have thought all along. It also affirms that the best-case scenario of little-to-no warming, which deniers point to as justification for inaction, is unlikely, as are the worst-case, “black swan” scenarios.

The study puts its best guess at 2.8C, which is pretty squarely in the middle of what scientists have thought all along. It also affirms that the best-case scenario of little-to-no warming, which deniers point to as justification for inaction, is unlikely, as are the worst-case, “black swan” scenarios.

But because the AFP write-up was framed around the worst-case scenarios being “not credible,” deniers are celebrating the study as some sort of win.

Now this study, and particularly AFP’s coverage, isn’t particularly helpful from either a scientific or a communications standpoint. For one thing, it’s based on recent short-term variation, not thousands of years of temperature data, like other paleo-climate based ECS studies. Plus, it uses a brand new modeling methodology–not exactly a tried-and-true approach. But apparently those who rail against climate models as hopelessly inaccurate will eagerly believe model outputs if they think it supports their denial.

Then there’s the whole “single-study-syndrome” issue, so we should take the findings with a grain of salt, especially given other recent studies putting ECS at the higher end of what’s likely. This new modeling exercise doesn’t take tipping points into account, meaning that – oops – those worst-case scenarios are still very much on the table if steady warming triggers rapid changes in glacier melt or ocean circulations or any other unexpected surprises.

[For more on climate sensitivity and long-term feedbacks, see here or check out pp 12-13 or our recent report on the scientific understatment of climate risks, What Lies Beneath.

And as we discussed last week, two significant pieces of work released towards the end of 2017 suggest that warming is likely to be greater than the projections of the IPCC, on which climate policy-making and carbon budgets are generally based. This is because ECS, an estimate of how much the planet will warm for a doubling in the level of greenhouse gases, is higher than the median of the IPCC’s modelling analysis:

- In “Greater future global warming inferred from Earth’s recent energy budget” published in Nature in December 2017, Brown and Caldeira compared the performance of a wide range of climate models (raw model projections) with recent observations (especially on the balance of incoming and outgoing top-of-the-atmosphere radiation that ultimately determines the Earth’s temperature), in order to assess which models perform best. The models that best capture current conditions (the “observationally-informed” models) produce 15% more warming by 2100 than the IPCC suggests, hence reducing the “carbon budget” by around 15% for the 2C target.

- In “Well below 2C: Mitigation strategies for avoiding dangerous to catastrophic climate changes”, published in September 2017, Xu and Ramanathan look at what are called the “fat tail” risks. These are the low-probability, high-impact (LPHI) consequences (“fat tails”) of future emission scenarios; that is, events with a 5% probability at the top end of the range of possible outcomes. These “top end” risks are more likely to occur than we think. When these are taken into account, the researchers find that the ECS is more than 40% higher than the IPCC mid-figure, at 4.5-4.7°C. And this is without taking into account carbon cycle feedbacks (such as melting permafrost and the declining efficiency of forests carbon sinks), and increase methane emissions from wetlands, which together could add another 1°C to warming be 2100.

Now those two papers don’t change the whole body of evidence about climate sensitivity. but they amongst an increasing number that conclude that ECS may be at the higher end of the IPCC range, especially when the so-called “longer-term” feedbacks (which are actually kicking in in relatively short time frames) are taken into account.

With thanks to Climate Central