Ed. note: originally published in the Spring 2017 issue of BC BookWorld (Vol 31., Number 1)

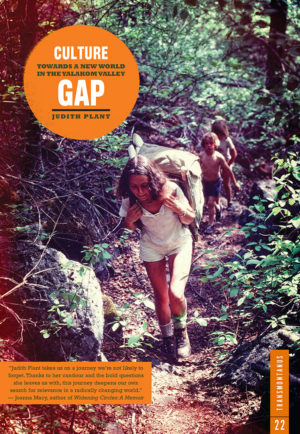

Culture Gap: Towards a New World in the Yalakom Valley

112 pages, 6×9 inches

Price: $19 CAD

ISBN: 9781554201334

Date published: 2017-05-25

Once upon a time within living memory, a lot of folks in B.C. wanted to try living in communes. Judith Plant was one of them.

As a single mother of three, she had gravitated from Fort McMurray (Fort McMud) to the West Coast where she was wooed and pursued at Simon Fraser University by a kind, handsome, English-born journalist and fellow Communications student, Chris ‘Kip’ Plant.

He had just spent seven years in the South Pacific helping Melanesian islanders liberate their small nations from the claws of colonialism, both French and English. “Add to this the misery of the diabolic, American nuclear testing in Moruroa and the Kwajalein Islands,” she writes in her memoir, Culture Gap: Towards a New World in the Yalakom Valley, “and Kip was near-to-seething with rage by the time we met.”

The soon-to-be romantic pair enrolled in Fred Brown’s 400-level Communications course on Community and Society and it changed their lives. An idealist who had bizarrely accepted Fidel Castro’s personal invitation to serve as head a new philosophy department in Havana after the Cuban Revolution, Fred Brown and his partner Susan also hosted lively Wednesday discussion groups at their “Clark House” residence in East Vancouver. Fred Brown’s wandering, intimidating intellect kept returning to one obsession: “What is community?”

Kip and Judith married in May of 1979. “Kip and I both agreed that the nuclear family is just too thin-on-the-ground,” she writes, “too fragile to support our children and ourselves.” Kip was fed up with political solutions and Marxist theorists. Their combined idealism and estrangement from conventional society led Judith to accept a job with Northwest Community College in Terrace as the first adult educator in New Aiyansh, a Nisga’a village in the Nass Valley.

As a couple, with three kids in tow, they left behind the concrete of SFU to live in a renovated trapper’s shack, in a cedar and spruce forest, on the banks of the Tseax River. Meanwhile Fred, Susan and some cohorts, most notably Van Andruss and his partner Eleanor and their baby girl, had similarly moved “back to the land” to a 160-acre quarter section in the Yalakom Valley, 30 kilometres from Lillooet, known locally as Camelsfoot.

Fred Brown wrote to them, quoting the idealistic “back to the land” character Miles Cloverdale from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novel, The Blithedale Romance, “…our courage did not quail. We would not allow ourselves to be depressed by the snowdrift trailing past the window…”

After Judith and Kip had taken their family to visit Camelsfoot in the spring of 1982, they learned their rented trapper’s cabin would be sold. They had to vacate in August. They decided to join Fred Brown’s commune in July.

Judith Plant’s memoir Culture Gap is concerned with describing how that isolated commune of sixteen people—more or less—survived and often thrived in the Bridge River Valley. Given that there are few too few books on the counter-culture, back-to-the-land movement of B.C. in the Sixties, Seventies and Eighties, hers is a very necessary and fascinating document.

Every commune—as they were ubiquitously called in those days—was very different; and all were also the same. In fifty fascinating pages Plant describes how the intellectually-driven but prudently practical Camelsfoot enclave learned how to milk goats, kill pigs and make head cheese while simultaneously engaging in heady, philosophical banter.

Her family slept in fire pit-heated tipis with the temperature dipping to minus twenty. Her kids learned how to use an adz and a log peeler. Everyone helped with the ambitious hydro-electric project. They made their own music. It was one for all, all for one, but she questioned the division of labour.

“While I sometimes thought I knew why I was at Camelsfoot and other times I was much less certain,” she writes, “I could only guess what motivated others and even that guesswork would probably end up being superficial.”

Feeding the firebox. Feeding the chickens. Feeding twenty people (there were often visitors) pancakes or porridge. Debating if cows were better than goats. Canning 85 quarts of applesauce, pears, cherries, peaches, apricots, tomatoes and plums. Escaping to the Reynolds Hotel in Lillooet for a clubhouse sandwich and fries. Getting horses. Getting lost on a solo hike up Independence Ridge. Tolerating the triple-seater outhouse. Shooting a deer. Vowing to never shoot another one. Having your ex-husband try to take your kids away.

It was all exhilarating and… exhausting.

Then Fred Brown, the patriarch, died. The gradual dissolution was painful. This, too, is universal for communes. As the commune began to unravel, outsiders could say, I told you so. “We couldn’t defend our beautiful dream of community to anyone,” she writes, “most importantly not even to ourselves. We were crushed. I started to cry, and I cried every day for a long time. Kip and I almost split up.”

A year after Fred Brown’s death, the Plants left the commune, buying a little cabin at the foot of the Camelsfoot trail, in close proximity, but independent.

The idealism of that shared Yalakom Valley experiment endures. Van Andruss has written an in-depth biography of Fred Brown, A Compass and a Chart: The Life of Fred Brown, Philosopher and Mountaineer (Lillooet: Lived Experience Press 2012) and he continues to live with his partner in the Lillooet area where he publishes his journal of non-fiction and poetry, Lived Experience.

*

Even though getting into Camelsfoot from Lillooet usually required a grueling hike—a description of which opens Plant’s memoir as she attends a recent Camelsfoot reunion—the Plants became involved in the Fed Up food co-op that was first funded by a $20,000 grant from the NDP government in 1972. Twice a year Fed Up published a broadsheet called The Catalist. In 1985, the Plants were inspired to publish their own periodical, The New Catalyst, which they published from Bridge River Valley for four years. There, Judith also edited a groundbreaking book on sustainability, Healing the Wounds: The Promise of Ecofeminism, published by New Society Publishers in Philadelphia in 1989. Fascinated with a new movement called Bio-Regionalism, the couple was well ahead of the curve and had already organized the third-continent-wide North American Bioregional Congress in 1986. By 1990 they were operating a Canadian adjunct of New Society Publishers.

In 1996, with the help of a silent partner, they eventually bought the bankrupt, Quaker-led publishing imprint based in Philadelphia, New Society Books, and soon moved their publishing headquarters to Gabriola Island as New Society Publishers. By 2005, they became the first publisher in North America to become carbon neutral, pioneering the use of recycled paper for books. Kip Plant died in Nanaimo on June 26, 2015 after courageously living with Progressive Supranuclear Palsy and Multiple System Atrophy for nine years. But the New Society imprint continues to serve as one of the most progressive and influential, hey-let’s-hurry-up-and-save-this-planet publishing companies in North America.