We have two reviews of The Minimalist Gardener by Patrick Whitefield, written by members. We think both offer valuable insights and reflections so have published them both together! You can buy the Minimalist Gardener at a special price direct from the publisher.

We have two reviews of The Minimalist Gardener by Patrick Whitefield, written by members. We think both offer valuable insights and reflections so have published them both together! You can buy the Minimalist Gardener at a special price direct from the publisher.

Review by Trish Whitham

The Minimalist Gardener brings together a series of 17 articles written by renowned grower, permaculturist and teacher, the late Patrick Whitefield and originally published in Permaculture Magazine over a period of more than twenty years. Big thanks are due to Permanent Publications for bringing these articles together into this very accessible and easy reading new reference book.

You should not sit down to read this book without a notepad to hand – you will probably need to keep a dedicated notebook for all the ideas and tips you will pick up and want to record and try out next season. I found it almost a complete practical gardening course that you can use as needed, a series of easy to follow practicals you will be itching to get out and try.

Patrick describes his minimalist ways – and the sometimes mysterious sounding permaculture principles and tactics – in simple, common sense, gardening terms. The term ‘minimalist’ refers to the amount of work put into maximising harvests and may be a more comprehensible term to draw interest from conventional gardeners.

Both novice and expert gardeners, conventional, organic and permaculturists will find new inspiration, ideas and step by step instructions – literally, on the dry stone step and path building section!

Whether dipping into individual sections of special interest or reading from start to finish it is a very engaging and motivating read destined to become a ‘go to’ reference book for the shed with mud stained, dog eared pages rather than sitting quietly on a bookshelf.

Increased yields and decreased effort – it is possible!

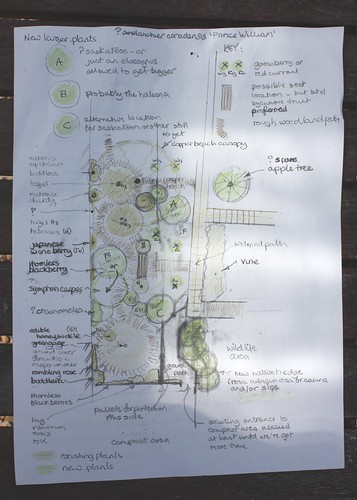

A bubble design for a garden

A bubble design for a garden

Minimalist gardening appeals to all gardeners – every grower is excited by the prospect of increased yields and decreased effort – it’s a dream for anyone trying to combine food growing with a busy life or ageing body. The Minimalist Gardener makes it all possible – we can all benefit now from the depth of experience and wisdom handed down to us by Patrick. It’s like having your own expert gardener on hand for whenever you have a ‘how could I do better, more easily, naturally, abundantly or sustainably?’ question.

Chapter one succinctly describes permaculture approaches to minimalist gardening with very clear, simple explanations that completely demystify the terms whilst gently and convincingly introducing some of the more revolutionary permaculture techniques that newbies can find a bit dubious. For example, the concepts and practice of no dig, polycultures, element placement and beneficial relationships. We are also guided on the benefits of observation, continuous evaluation and base mapping in order to come up with designs that will keep working for us into the future and can be tweaked and improved each year. This section is particularly helpful when it’s time to to start planning (or revolutionising) your plot for the next year, it’s also reassuring to conventional gardeners that they can make gains just by tweaking their existing practices and they don’t have to completely redesign from scratch.

The following 16 chapters each cover a specific aspect in detail and I found helpful wisdom and instruction in each but especially enjoyed the chapters on seeds and plants, shady gardening, slug controlling, perennial vegetables, pruning and building paths and steps.

Tried and tested perennial vegetable options

CC BY-NC 2.0 by Emma Cooper on Flickr www.flickr.com/photos/fluffymuppet/15050935806

CC BY-NC 2.0 by Emma Cooper on Flickr www.flickr.com/photos/fluffymuppet/15050935806

I went straight to the chapter on Patrick’s favourite perennial vegetables hoping to discover some new tried and tested food plants that just keep delivering without needing to be sown each year.

I was excited to find a rare example of a perennial root vegetable popular in medieval times called skirret. These grow in clumps of long, thin, knobbly roots a bit similar to the Jerusalem artichoke and were a regular crop in Patrick’s plot. They look as though they would just need a good scrubbing to prepare and are apparently very tasty, sweet and a good source of carbs cooked or raw. I am now on the lookout for an organic tuber!

There were plenty of other suggestions to try out as well including pink purslane, sea beet, and herb patience as well as more familiar perennial kales and broccoli. I also learned that the scary sounding ‘weed’ hairy bittercress is neither hairy nor bitter! I will try that next year for salad leaves.

Next I turned to the pruning section, an area I have yet to learn and practice myself, I was not really sure why people pruned fruit trees but now I understand how pruning increases crops, reduces diseases and makes harvesting easier. I found easy to understand instructions, examples, illustrations and loads of professional guidance passed down from Patrick’s long experience. This section gave me the confidence and interest to be able to volunteer at the next pruning session in a nearby orchard and gain some hands on experience. There is also a whole section on fruit that could be a great time saver, learning from others’ experience.

Minimalist design opens up a path to abundant harvests

Building a drystone path

Building a drystone path

Food growing often has a reputation for needing lots of hard digging, double digging and more digging, weeding, watering, fertilising, pest elimination and constant attention – so understandably most people prefer to buy their fruit and veg from the labours of others. At the same time, more people are becoming aware of the destructive and toxic nature of industrial farming practice, health and environmental impacts, monopolies and questionable ethics of agrochemical and seed companies and the big land owners.

More and more people are starting to grow at least some of their own food, naturally and chemical free, many are successful but every allotment has its lonely, abandoned plots enthusiastically taken on by new gardeners who soon exhausted themselves, often in their first year. It can quickly become impossible to combine the hard labour of conventional growing practice with busy careers and family life. The Minimalist Gardener has the potential to regenerate some of these plots and re-enthuse the disillusioned as once a minimalist design is implemented that is the end of hard labour and the beginning of abundant harvesting with minimal management.

Minimalist and permaculture gardening can seem aesthetically untidy, unruly and potentially out of control and even dangerous to conventional gardeners. Especially if neighbouring growers have spent years putting huge effort into digging, clearing, weeding, eliminating undesirables and feel proud of their efforts to keep their plot one of the most exemplary for well dug neatness.

It’s only when tidy gardeners are encouraged and supported to look past current norms and gaze deeper into the tangled web of nature that they begin to see the promise, the beneficial relationships, ability to regenerate healthy soil naturally that they come to understand that it’s not lazy gardening but totally practical – many will gradually develop a preference once they have the opportunity to study permaculture practice and visit demonstration sites. This book could be a catalyst for such gardeners to explore out of their comfort zone and into the heady wilds of minimalism.

If you know a gardener who complains of backache, blistered hands and who has little leisure time in the growing seasons this book could be a life changer! Tweet this

It can be lonely being the ‘weird’ and ‘untidy’ one on an allotment and can cause bad feeling and complaints – in some sad cases councils have ploughed up long established, productive permaculture gardens because they were reported as ‘too untidy’ or ‘neglected’ and accused of being a source of weed seeds and slugs. In the last chapter Patrick takes a look at permaculture beyond our own gardens and plots and gets us thinking about how we can move toward collaboration and integration with neighbours and wider communities.

I can see a use for this book as an instigator and guide for informal workshops down at the local allotment.

Finally, I was encouraged by this quote from Patrick and the hopeful idea that we could actually begin to make a positive impact ecologically instead of just being less bad:

“Growing our own food is not only a satisfying and enjoyable thing to do, but it’s also one of the most positive actions we can take to turn our negative ecological impact into a beneficial one.”

A second review

Patrick Whitefield by Laura Gibbs

Patrick Whitefield by Laura Gibbs

Minimalism has been a hot topic in the last few years, with its bold claims to saving the world through reducing consumption levels. But there is much more to the topic than just giving away all our stuff and not buying anything new. The core of the minimalist movement is to free up time, bring meaning back into our lives and as Joshua Becker of Becoming Minimalist adeptly puts it: “to live more by owning less.”

Minimalism complements permaculture because both disciplines ask us to look at our lives, the systems behind things and to think beyond the current global narrative that’s leading us toward ecological collapse. It is quite fitting that this latest release focuses on minimalism in the garden, but perhaps the title is a little misleading. The book isn’t focused on creating a beautiful, clean, zen-like ‘minimalist garden’ as the title might conjure up. Rather the book focuses on minimising time and energy spent gardening while maximising yield and improving our ecological footprint by growing our own food right in our gardens.

The Minimalist Gardener is a collection of articles by Patrick Whitefield first published in Permaculture Magazine, aimed at sharing his experience and encouraging us to grow even a little of our own food. Patrick was an early pioneer of permaculture, adapting much of Bill Mollison’s teachings to the cooler British climate.

As well as many years working in agriculture, Whitefield was also a permaculture teacher (even developing the first online Permaculture Design Course), and a prolific writer. His books include: Permaculture in a Nutshell (1993), How to Make a Forest Garden (1996), Tipi Living (2000), The Living Landscape (2009), How To Read the Landscape (2014) and the renowned Earth Care Manual (2004), an authoritative resource on practical, tested, cool temperate permaculture. Patrick was also a consulting editor to Permaculture Magazine since its launch in 1992 until his death in 2015.

It is obvious from his writing that Patrick loved nature and held a deep concern for the earth and its people. In The Minimalist Gardener Patrick’s belief that gardening would connect us to nature and also tackle the environmental costs of today’s food production systems is evident in every chapter. He offers advice, hints and tips, as well as a chapter applying permaculture principles beyond the garden.

CC BY-NC 2.0 by margoc on Flickr www.flickr.com/photos/margoconnell/5893385425

CC BY-NC 2.0 by margoc on Flickr www.flickr.com/photos/margoconnell/5893385425

Despite being made up of separate articles written over a number of years, The Minimalist Gardener has a sense of flow and ease to it, taking the reader step by step through the concept of minimal gardening. The writing is clear and eloquent and yet it is dense with decades of knowledge and experience.

From dry beds and garden paths to seeds, plants and perennials, each chapter has incredibly valuable information for both novice and experienced gardeners. Patrick has also taken the time to think out each plant recommendation, based on its energy, food offerings and time demands. For example, he favours self seeders and ‘cut and come again’ plants over single harvests, and takes care to explain the importance for planning for continuity so the garden is producing food all year round. The true minimalist garden would have fast growing crops to increase the overall yield of produce. Purple sprouting broccoli then would be out as it needs to stay in the ground for long periods of time. However, if you wanted to grow it you could interplant the broccoli with fast growing crops like lettuce to maximise space usage.

Getting an incredible amount of food from a small space

Cristina Crossingham’s recycled urban garden

Cristina Crossingham’s recycled urban garden

Throughout the book, Patrick provides a guide to getting an incredible amount of food from a small space. The combinations mean ‘minimalist’ gardeners have more plants per square metre than in a monoculture. The ground is covered more completely and quicker, so weeds get less of a look-in, again meaning less work.

Accidently, or perhaps this was Patrick’s grand vision, the articles and subsequent book, The Minimalist Gardener, have created a blueprint for any gardener to follow for an incredibly nutrient dense, high yield garden. It is clear from each chapter that Patrick Whitefield embodied the essence of permaculture in everything he did.

Going beyond the garden, the last chapter links the ethics of earth care, people care and fair shares to our lives. He offers ideas on how we can learn from ecology and reduce our impact while getting our needs met and living a joyful life.

Regardless of the reader’s knowledge of permaculture, The Minimalist Gardener has the ability to change any sized British garden into a food forest and for this alone, I recommend The Minimalist Gardener to anyone looking to start a kitchen garden, minimalist backyard or allotment. It seems that to Patrick Whitefield, being a minimalist gardener doesn’t mean a garden of less, but rather a garden of plenty, especially when compared to the time put into the initial space.