In conversations with all sorts of people, on the topic of what I’m doing and why, I’m often struck by the muted response to how truly precarious our present moment in history really is. We are living at a time of severe ecological degradation and loss, in what may be the terminal decades of our global industrial civilization if we remain on the path we’re on (which at times it seems we’re singularly determined to do). And yet these astounding facts are treated almost as mundane oddities or an uncomfortable kind of fiction. But they’re not.

Admittedly, it’s not that surprising that many struggle to grasp the seriousness of the situation. A clearer understanding of the urgent and unavoidable nature of the existential threats we face is gained only through dedicated study of a broad range of fields and the complex interactions between them. This is impractical for most, and requires (improbably) that they first come to realize the need for it. Besides this, most of us are simultaneously short on time and saturated with narratives telling us that all will be well if we only buy this product, that ideology, or simply place our faith in the disembodied genius of mankind.

These narratives treat the dominant economic paradigm, or rather sanitized components of it such as innovation and entrepreneurship, with an almost mystical reverence. The champions of progress have been selling a careful story, echoing (or bastardizing?) Voltaire, Marx, Keynes and other utopian thinkers of the 19th and 20th centuries. We are told that what awaits us is a technological paradise; a gleaming post-scarcity society. The details change as trends come and go. The galaxy will be ours, if only we trust in Musk to get us there. Work will be obsolete, if we can tame our own creations. We can step out of the darkness and realize our ultimate potential.

When we as a community raise our voices, and insist that the economy is a subset of the natural world, they nod in agreement. When we reach further and claim that, within the bounds of a finite biosphere, those of us who live in the developed world may have to make sacrifices to allow the less fortunate to extract themselves from poverty, they shrug, and continue living the only lives they’ve ever known. And if we’re honest, so do we. Such is the nature of the comfortable but fleeting impasse we find ourselves in. So far, the hard realities of a finite world haven’t really begun to visibly shape our daily experience. The machine is still humming.

The most telling thing is that there’s no clear, concise, widely-recognized term for this field of research. Ecological economics, sustainability science, degrowth, decolonization, environmental justice and so on are all labels which hint at distinct aspects of the overall problem. But behind these labels lies a global economic system which has grown far too large, far too rapacious and is very ‘efficiently’ extracting the irreplaceable value from nature and concentrating symbolic representations of it in the hands of the few, while giving little more than empty promises, misery and environmental desolation to the rest. It’s not even as simple as saying that we’re anti-this, because it’s much easier to agree on what’s wrong than on what we should aspire to.

All of this is to say, it is easy to feel small when standing up against the destructive momentum of late-stage extractive capitalism. And this is particularly true when all of us are deeply dependent on the very system we are fighting against. I’ve found that myself and more than a few others working in related fields oscillate between enthusiasm and excitement in what we’re working on and a deep, insistent suspicion that it’s just not enough. Exuberant one minute, defeated the next. And all this is on top of the normal stresses of graduate school, life and the seemingly fading employment prospects in a faltering, full-world global economy. We’re faced with the impossible choice of working towards a livelihood post-graduation, or the contrarian path of embracing the world as we know it to be.

—

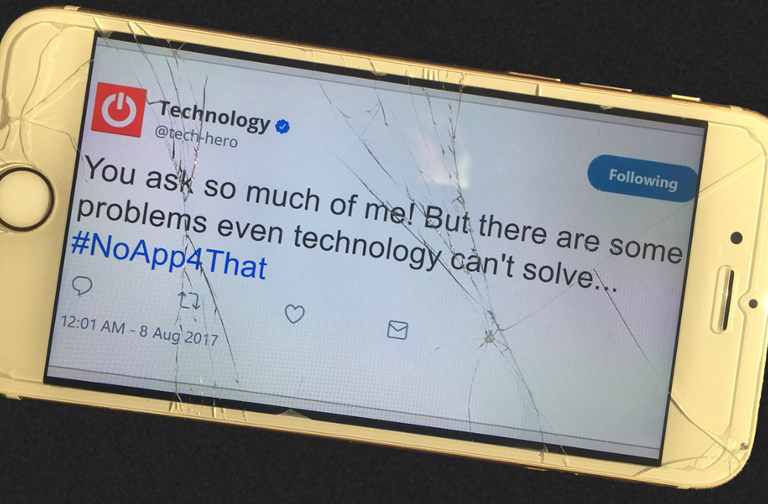

This summer I carried out an internship with the Post Carbon Institute, an NGO I’ve admired for years. PCI focuses on producing essential, solid analysis of the energy trends shaping the sustainability debate. Notably, they don’t buy into the hype around ‘Saudi America’ or any of the other misinformation out there detracting from the very real need to question how we use energy, for what, and how we intend to keep doing that in the future. Recently, PCI have also branched out into broader commentary regarding other aspects of modern society, including our troubling relationship with technology. This is where I came in – to assist with the preparation of a manifesto entitled There’s No App For That: Technology and Morality in the Age of Climate Change, Overpopulation and Biodiversity Loss (find it online here).

My contribution was primarily to explore several case studies and side topics to support the arguments made in the main text. These topics ranged from the dark side of smart devices and social media in our lives to the absurdity of feeding a global population of over nine billion by 2050 without changing our self-defeating approach to food. This involved a lot of research, including some topics I had very little background in, and a lot of work with the lead author and other contributors to craft a careful, cohesive story throughout the report. This story draws attention to our perilous tendency to appeal to technology as an alternative to dealing with the real, pressing moral questions implied by ecological limits. I was surprised and pleased with how much overlap there was with ecological economics, the focus of my PhD program, and how far these disparate voices can be aligned in practice.

Most of all, this experience taught me that although it is very easy to feel isolated in this fight, we have many unseen allies coming from different angles and conceptual backgrounds, but ultimately with the same fundamental objectives. All we lack is a language and identity to bring us together. The words are there but the relationships behind them haven’t really caught up yet.

At the wider level the conversation is slowly beginning to change. Stories critical of the future of capitalism in its current form (or at least acknowledging that neoliberalism is on the defensive) are now appearing in mainstream outlets such as the New York Times, The Economist and even the Wall Street Journal. Crucially, an alternative is becoming more and more conceivable, however far away it may be. This shift is long overdue, there’s still a long way to go, and there’s no guarantee that this is a sign of change sufficient to arrest the worst impacts of our devastating ecological legacy, but hope is a powerful thing.

We are witnessing an expansion of the discourse to include previously unmentionable moral considerations, beyond a vague, Brundtland-esque responsibility to future generations paid as easily in financial compensation as in functional ecosystems. There is a growing realization that despite what the champions of progress tell us, we can’t just grow and invent our way to plenty, and we can’t continue to ignore the disasters we’re inflicting on those who already suffer the most from our unrelenting demands on nature. And maybe this is not enough, but it is enough to keep trying.