The story of the Club of Rome starts with the issue of natural resources. In the 1960s, it had become clear to the Club’s founder, Aurelio Peccei, that the world’s resources were finite and to ask the question of how that was to affect humankind. It was the origin of the first and the best-known report to the Club of Rome, “The Limits to Growth,” published in 1972.

The 1972 report already provided answers to the question of depletion. It turned out that resource scarcity would limit the growth of the world’s economy and, eventually, lead it to decline. This conclusion was often misunderstood as meaning that humankind would soon “run out” of oil, gas, or some other resource; but that was never stated in the report and it never was the point.

The 1972 report already provided answers to the question of depletion. It turned out that resource scarcity would limit the growth of the world’s economy and, eventually, lead it to decline. This conclusion was often misunderstood as meaning that humankind would soon “run out” of oil, gas, or some other resource; but that was never stated in the report and it never was the point.

In 2014, the Club of Rome produced another report titled “Extracted” in English and “Der Geplunderte Planete” in German that reiterated the earlier conclusions. The author of the report, Ugo Bardi, a researcher at the University of Florence, Italy, concluded that the problem of mineral depletion was real and that it was progressively getting worse.

Yet, these conclusions are far from being generally accepted. Depletion, it seems, is still considered a non-problem, especially in the extractive industry. “If depletion is really a problem,” industry representatives often say, “how come that we are still producing mineral commodities at the highest rates ever seen in history? Besides, we observe that our production costs are not significantly increased when we use lower grade ores.”

So, is mineral depletion an existential threat to human civilization? Or is it just a marginal problem that can be fixed by some technological improvements? This is truly a fundamental question for the future of humankind. An answer is provided by the latest report to the Club of Rome that was published in 2017, “The Seneca Effect.”

So, is mineral depletion an existential threat to human civilization? Or is it just a marginal problem that can be fixed by some technological improvements? This is truly a fundamental question for the future of humankind. An answer is provided by the latest report to the Club of Rome that was published in 2017, “The Seneca Effect.”

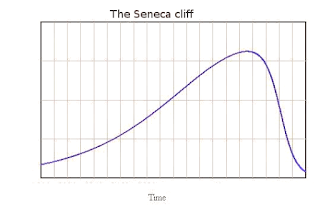

Taking inspiration from something that the ancient Roman philosopher Seneca said, the author of the study, Ugo Bardi, examines the trajectory of an economic system subjected to the dual strain of mineral depletion and pollution. The result is the “Seneca Curve”, a graphical depiction of Seneca’s statement that “Increases are of sluggish growth, but the way to ruin is rapid.” It is something well known in everyday life, but the study could confirm it using mathematical models. Here is the curve as calculated by simulations.

The “Seneca Effect” or the “Seneca Paradox” explains why mineral depletion is a problem but, at present, we are not feeling its effects. We haven’t yet reached the summit of the curve and we are not seeing the cliff awaiting us. So far, the extractive industry has been able to mask the effects of depletion by means of economies of scale. That has been possible as long as production keeps increasing, which has been the case up to now for most mineral commodities. The problem is that this strategy cannot last forever: mineral resources are not infinite.

A good example of this effect can be found in the oil industry. At present, all fears of “running out” of oil seem to have been dispelled by the low market prices and by the still increasing production. Both factors give the impression of an abundance of cheap oil that could last for a long time – if not forever. But this is exactly the result of the shape of the Seneca Curve. As long as we don’t reach the start of the cliff, we don’t see it.