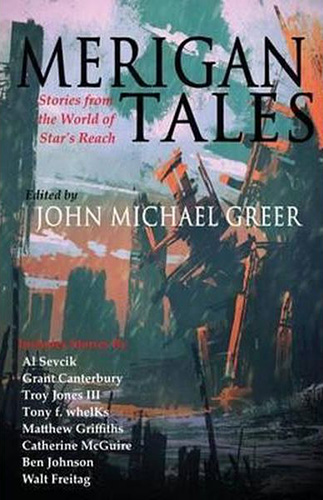

Merigan Tales

Stories from the World of Star’s Reach

Edited by John Michael Greer

(Founders House Publishing, December 2016, 289 pages, $16.99)

The stories that fill this extraordinary volume depict a far-future world that defies most people’s expectations about the future. In it, America and the other developed nations have reverted to a preindustrial state of existence as a consequence of having exhausted the Earth’s economically recoverable fossil fuels as well as rendered immense regions of the planet humanly uninhabitable in the process. Throughout the formerly industrialized world, people have had to invent new modes of living, ones that can be sustained with renewable resources. The result has been a wild profusion of diverse human societies whose attitudes and everyday experiences differ starkly from ours.

The speculative future outlined above was first brought to life in John Michael Greer’s 2014 novel Star’s Reach. Greer’s tale takes place some 400 years from now in what today is the American South, and concerns a quest to uncover one of the 21st century’s darkest, most enduring secrets. The main characters journey to a faraway, long-abandoned research station where scientists from the 2050s are rumored to have contacted alien life in a last-ditch bid to save the crumbling industrial age by way of extraterrestrial intervention. Along the way we’re given a fascinating tour of one particular corner of 25th-century America—or “Meriga,” as it’s now known.

A shared-world anthology, Merigan Tales presents eight new stories by authors inspired enough by Star’s Reach to incorporate its milieu into their own fiction. None of these pieces can really be considered a sequel or prequel to Greer’s novel, though a couple do allude fleetingly to its events. Some take place before Star’s Reach, others concurrently with it and still others afterward. Greer, who edited this collection, chose to order the stories more or less chronologically, a move that helps ease us into the radically altered world that they present.

Among the more poignant themes of this book is the profound influence that today’s technologies, though long gone, continue to exert on people’s thinking and behavior. Some people despise the machines of old, while others pray for their return. Whatever one’s particular feelings about industrial-age technology, however, the one constant seems to be that everyone spends a great deal of time thinking about it and the time in our history that it represents. The places where it’s least well regarded tend, justifiably, to be those that have been most ravaged by climate change and other ecological calamities. In such regions, those suspected of trying to bring back the old ways often face draconian punishments. (While this isn’t referenced anywhere in Merigan Tales, we learned in Star’s Reach that there are communities where the penalty for drilling for oil is live burial.)

Among the more poignant themes of this book is the profound influence that today’s technologies, though long gone, continue to exert on people’s thinking and behavior. Some people despise the machines of old, while others pray for their return. Whatever one’s particular feelings about industrial-age technology, however, the one constant seems to be that everyone spends a great deal of time thinking about it and the time in our history that it represents. The places where it’s least well regarded tend, justifiably, to be those that have been most ravaged by climate change and other ecological calamities. In such regions, those suspected of trying to bring back the old ways often face draconian punishments. (While this isn’t referenced anywhere in Merigan Tales, we learned in Star’s Reach that there are communities where the penalty for drilling for oil is live burial.)

In places where the technology of our time is sorely missed, people are desperate to believe in anyone who purports to be able to bring back the machines. The main character in Al Sevcik’s “The Second Coming” is one such person. Everywhere he goes, he’s seen as a messiah figure—until, that is, he proves incapable of delivering on his promises, at which point he finds himself unceremoniously run out of town. He’s a challenging protagonist because, while he doesn’t set out to deceive people, he’s clearly a disturbed individual. He hears imaginary voices imploring him to confront the leader of what’s left of the United States and demand the machines’ return. He lashes out at anyone who opposes him. The pressure he feels to carry out the commands in his head distresses him greatly. As he tearfully explains to Nora, his one friend in the world, “I want them to leave me alone. I’m not smart enough to do what they want, Nora.”

For the most part, those who desire a revival of the previous age have an incomplete understanding of why it went away and why it can’t be brought back. The central character in Sevcik’s story believes that the machines were probably taken away for some legitimate reason—but that, whatever this reason, it has surely become moot at this point, so all that’s needed is to persuade the elites who hid the machines that it’s now safe to make them available again. Only a few people seem to know anything of the laws of physics that stand in the way of such an endeavor, no matter how much people at any level of society may want to undertake it. In one of the crowds that gather around Sevcik’s hero, we hear one such man lucidly explain, “I was told the machines needed energy, more than we can get from the sun and the wind.” Yet clearly this well-informed person is an outlier.

In Troy Jones III’s exciting mystery “Tiny’s Legacy,” we meet a cabal of shady characters who will stop at nothing to learn the location of the fabled research facility we were introduced to in Star’s Reach, which they’re convinced holds the key to restoring the old world. The story’s lead character, Danna, is an impetuous, physically imposing young woman who can hold her own against most men in a fight. Employed as a “burner”—or one charged with incinerating the deceased and then safely disposing of their ashes—she one day happens upon the corpse of a suspicious out-of-towner. As she attempts to gather clues as to the man’s identity and the reason he turned up dead in her community, she becomes involved in a high-stakes clandestine operation. The result is a taut, intelligent thriller told from the viewpoint of a wonderfully fierce heroine.

Catherine McGuire’s “Elwus has Left the Building” supplies excitement of a different sort, in this case an archeologist’s thrill at making a momentous find. Though archeology no longer exists as a profession, important discoveries about the past continue to be made by connoisseurs of ancient artifacts. It’s common for such people to be employed as “ruinmen,” or those who demolish old buildings for their scrap. Indeed, one of the main characters in McGuire’s piece is a young ruinman’s assistant. She plays a key role in figuring out the true location of the famous Graceland mansion where Elvis Presley (now reverently called “King Elwus”) lived out his final years. Our other chief character is a young “elwus” (i.e., Elvis impersonator) who is enrolled in a sort of elwus boot camp. McGuire’s story is great fun and replete with delightful Easter eggs for those familiar with Elvis’ actual life and times.

“Silent Key” by Tony f. whelKs is another story about the adventure of discovery. An avid amateur radio operator, whelKs has long seen the potential of small-scale, amateur radio to maintain communications in the event of disasters that take out conventional channels. (Just recently, this potential was on sharp display when, following Hurricane Maria, volunteer ham operators enabled Puerto Ricans to reconnect with family and friends on the U.S. mainland.) “Silent Key” is set at a time when amateur radio is not merely a backup form of communication pursued mostly by hobbyists but the dominant mode by which communities stay in touch. The story’s main character is an Australian “radioman” who stumbles on a transmission from Meriga—and in so doing finds the first evidence of transatlantic radio propagation that anyone has encountered in more than 200 years.

The story described above isn’t the only one that curiously takes place far away from Meriga; there’s also Matthew Griffiths’ “Journey to the North.” This one is set in China, a country to which Griffiths, a New Zealander, has devoted much study, according to his contributor bio. Griffiths accomplishes an impressive feat here, conjuring up a richly realized setting that feels at once futuristic and ancient. Central to the story’s plot is a project to construct the largest stone Buddha in China—no mean task, given the absence of modern-day machines.

The remaining three stories cover a wealth of thematic ground and take place across the world’s northern reaches. “Eight Stars of Gold” by Grant Canterbury depicts life aboard a whaling boat at a time when the Arctic is navigable year round and Greenlun (i.e., Greenland) is an ice-free island chain. In Ben Johnson’s “Over the Top of the World,” a naval fleet sails north from the coast of Nuwinga (a new nation consisting of what is now New England) to defeat a band of pirates in the Balteka (i.e., Baltic Sea). Lastly, “The Heart of Winter” by Walt Freitag is about a man who rescues a hypothermic woman he encounters in the midst of a mountain blizzard. The two turn out to hold diametrically opposed belief systems—one founded on seeking the blessings of a deity, the other on abiding by one’s own moral compass—and as the woman awakens in the shelter set up for her recovery, they have a fruitful discussion about their disparate worldviews.

It would be easy for a book like this to feel unbearably oppressive, and to take glee in its bleakness. Yet this isn’t the way that Merigan Tales comes across. In so many ways, our contemporary experience is already indistinguishable from dystopian fiction; all that the stories in this volume do is take current trends to their logical conclusions. In their shared future, as in our present world, there is much to dread as well as to be thankful for, and people see just as much reason to live and have hope for the future as people today generally do. As Greer beautifully puts it in his foreword, here is “a future in which individuals and societies have had to come to terms with the hard limits of a finite planet, and gone on to live their lives anyway.”