A visit to Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary shines light on the benefits of safeguarding oceans for everyone.

October 3, 2017 — Much of what lay beneath the ship was a mystery. The edge of the continental shelf plummets more than 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) somewhere in the vicinity of oceanographer Robert Ballard’s Exploration Vessel (E/V) Nautilus, which was making its way to Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary, about 60 miles (97 kilometers) northwest of San Francisco.

They say there are better maps of the moon and Mars than of Earth — some 70 percent of this planet’s surface is under water, and water disrupts radar signals needed to generate high-resolution maps. Most maps of the ocean floor have a resolution of 5 kilometers (3.1 miles), meaning only objects with about that diameter or larger are discernible.

The 211-foot (64-meter) ship left port at 9 a.m. on August 6 on a nine-day mapping and exploration expedition with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to help resolve some of that mystery by sending remotely operated vehicles, or ROVs, down to identify new habitat areas and ocean floor topography. I joined the team as a science communication fellow funded by Ocean Exploration Trust, which owns and operates the E/V Nautilus.

We lingered on the outer decks, in spite of the strong winds and chilly air, eager to be underway. Within two hours our first wildlife sightings — humpback whales, common murres, black-footed albatross — hinted at the abundance of life unseen below the surface. The sanctuary’s boundary is 6 miles (9.6 kilometers) off the coast, where the presence of shipping lanes through and around the sanctuary and near-constant 15- to 20-foot (5- to 6-meter) waves make it difficult to visit for fishing and wildlife spotting. Those barriers act as a buffer, making the sanctuary favorable for scientific study.

“It’s often really rough waters; that might be one of the built-in protections that makes it such a special place — it’s really limited human activity out there,” says Jennifer Stock, education and outreach coordinator for the sanctuary. Since the sanctuary is entirely offshore it is also protected from some of the impacts seen near shore areas next to densely populated regions, such as agricultural and pollutant run off, according to Danielle Lipski, research coordinator for Cordell Bank and lead scientist for the expedition.

In spite of the sanctuary’s inaccessibility, Stock explains, the public was outspoken in its support for establishing it in 1989, and then expanding it in 2015 from 529 to 1,286 square miles (851 to 2,069 square kilometers), because sanctuary status protects an area from oil and gas extraction.

Earth’s Nurseries

The U.S. National Marine Sanctuary System was established in 1972 to protect specific areas with “conservation, recreational, ecological, historical, scientific, cultural, archeological, educational or esthetic qualities.” It was three years after a massive oil spill dumped 3 million gallons (1 million liters) of crude oil off the coast of Santa Barbara, kick-starting an environmental movement that helped contribute to the establishment of marine sanctuaries and key pieces of environmental legislation, including the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act and the National Environmental Policy Act.

Today the system’s more than 600,000 square miles (1.5 million square kilometers) of marine and Great Lake waters include two marine national monuments, Rose Atoll and Papahānaumokuākea, and 13 national marine sanctuaries.

Executive Order 13795, issued by President Donald Trump in April 2017, opened a review process on newly expanded territories within marine sanctuaries, meaning that areas expanded by previous administrations could be opened up for resource extraction. A period of public comment on this review closed in early August; no decisions have been announced and there is no indication that Cordell Bank has been targeted, but the action serves as a reminder that protected areas could face future threats.

The sanctuaries are valuable in many ways. They are considered sentinel sites for monitoring changing conditions, educating the public and, perhaps, serving as early warning mechanisms for ocean acidification, harmful algal blooms and other impacts human activity has on the ocean — which we are just beginning to understand. And, if the ocean is our planet’s life support system, then national marine sanctuaries are its nurseries — supporting myriad species, some of which we have yet to discover and many of which most humans will never see with their own eyes.

A Different Way to Think

This is in part what this trip is all about: Stock spends much of her time working to help people value a place they can’t see or visit in person. “From invertebrates to blue whales to deep-sea corals and everything in between, to have such an incredible diversity of life in such a small area is really a special treasure. It’s really worth celebrating and protecting,” she says.

Each summer, ocean wind and currents bring nutrient-rich water from the deep ocean to the surface in a process called upwelling. Thanks to this California current ecosystem, leatherback turtles have been lured from Indonesia, an amazing 8,670 miles (13,953 kilometers) to travel for a meal of brown sea nettles. Blue and humpback whales journey from South America and Mexico to gorge on krill. And seabirds, such as pink-footed shearwaters, soar above the blue waters of the Pacific Ocean dining lavishly on fish, crustaceans and squid.

“This whole area is this incredible food web hot spot — extremely abundant with life,” says Stock.

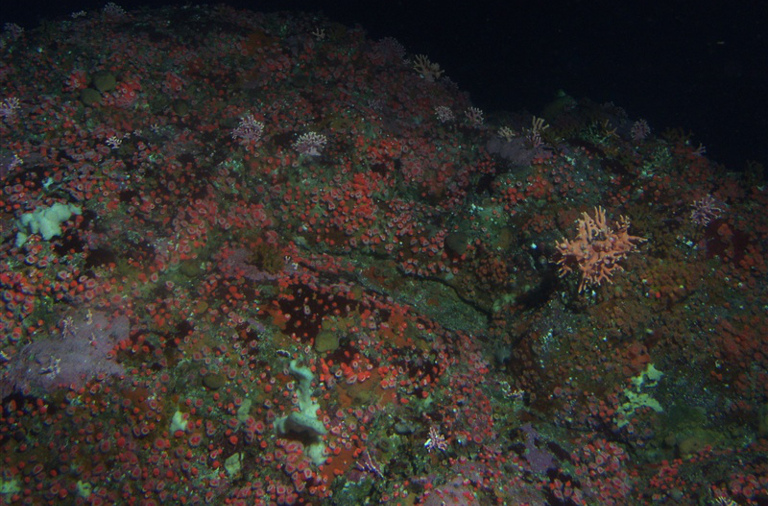

Meanwhile, rocky habitats provide something for marine invertebrates to cling to on the ocean floor. One key feature of the sanctuary is Cordell Bank, a granitic rocky underwater island. It offers rich habitat for corals, sponges and a host of marine organisms.

“This makes it an attractive place for other animals to come to, like rockfish and mobile invertebrates like sea stars and crabs and giant octopus,” explains Stock. “It becomes this little city in the middle of nowhere.”

Armed with ROVs outfitted with high-definition cameras and tools for collecting samples in a deep water environment, the team of scientists and engineers from NOAA and E/V Nautilus set out to discover what else they could find within the sanctuary. They were not disappointed. In cold, dark waters, more than 8,000 feet (2,438 meters) deep, the ocean floors of Bodega Canyon and a neighboring unnamed box canyon were teeming with life. To Lipski, it was incredible to see these hot spots, and particularly some deep sea corals that had never been observed in the sanctuary before.

The team conducted over 92 hours of ROV dives, recorded volumes of video footage and collected hundreds of samples, which were shipped to universities and research partners around the country so they could study the biology, chemistry and geology of the region. Meanwhile, I answered questions from viewers who tuned in from all over the world to see what we were seeing while scientists conferred about what samples to collect and the navigator and ROV pilots moved from spot to spot along a predetermined path. Collective exuberance at catshark, octopus and skate sightings punctuated the quiet moments during our watches.

Until this trip, Lipski and her team’s understanding of what might be on the ocean floor were based on expeditions in similar, shallower locations in the region. Characterizing these deep-water habitats will strengthen their capacity to manage this resource, which is important scientifically as well as economically. According to NOAA, the national sanctuary system contributes about US$8 billion to local economies through tourism, fishing and research — contributions that emphasize the potential impact of our efforts on this voyage.

Lipski says the expedition offered a different way to think about the sanctuary. Now they have sense of what is out there, which will help them to better communicate with constituents and to educate the public about this resource. And they are armed with information to guide future research and exploration.

“It was kind of a blank slate,” she says. “Now we think, wow, we’ve really got to get back out there.” ![]()

Teaser photo credit: Jodi Pirtle/NOAA/CBNMS