Where did things go wrong on the way to modern life, and what should we do instead? This question always seems to lurk in the background of our fascination with many indigenous cultures. The modern world of global commerce, technologies and countless things has not delivered on the leisure and personal satisfaction once promised. Which may be why we moderns continue to look with fascination at those cultures that have persisted over millennia, who thrive on a different sense of time, connection with the Earth, and social relatedness.

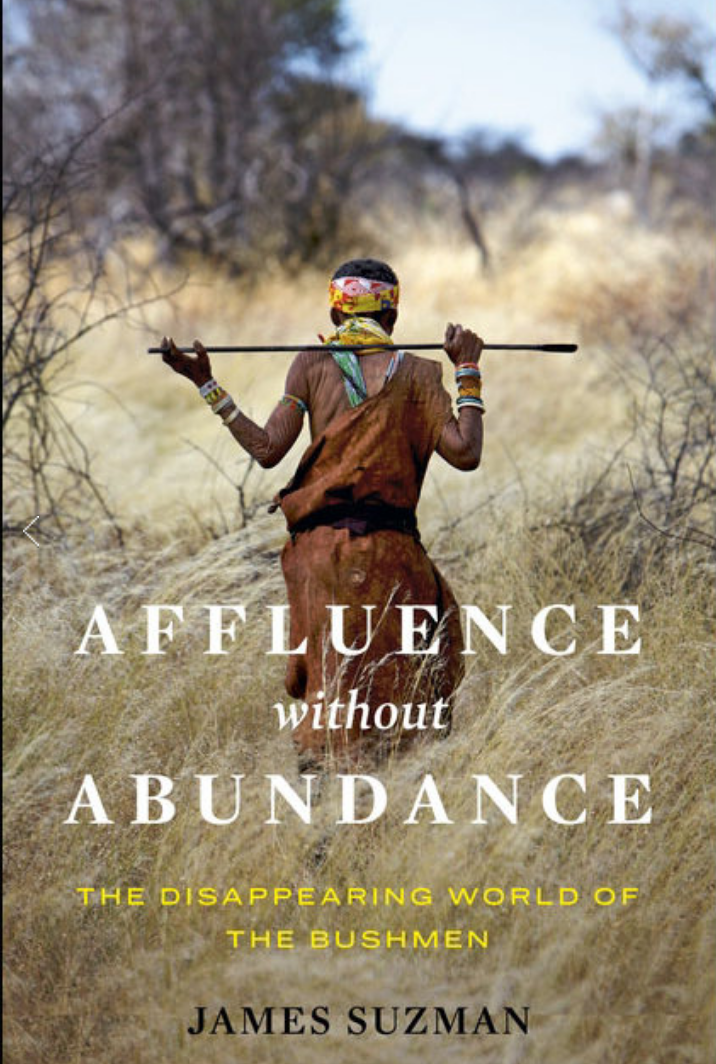

Such curiosity led me to a wonderful new book by anthropologist James Suzman, Affluence without Abundance: The Disappearing World of the Bushmen. The title speaks to a timely concern: Can the history of Bushmen culture offer insights into how we of the Anthropocene might build a more sustainable, satisfying life in harmony with nature?

Writing with the emotional insight and subtlety of a novelist, Suzman indirectly explores this theme by telling the history and contemporary lives of the San – the Bushmen – of the Kalahari Desert in Africa. The history is not told as a didactic lesson, but merely as a fascinating account of how humans have organized their lives in different, more stable, and arguably happier, ways. The book is serious anthropology blended with memoir, political history, and storytelling.

After spending 25 years studying every major Bushman group, Suzman has plenty of firsthand experiences and friendships among the San to draw upon. In the process, he also makes many astute observations about anthropology’s fraught relationship to the San. Anthropologists have often imported their colonial prejudices and modern alienation in writing about the San, sometimes projecting romanticized visions of “primitive affluence.”

Even with these caveats, it seems important to study the San and learn from them because, as Suzman puts it, “The story of southern Africa’s Bushmen encapsulates the history of modern Homo sapiens from our species’ first emergence in sub-Saharan Africa through to the agricultural revolution and beyond.” Reconstructing the San’s 200,000-year history, Suzman explains the logic and social dynamics of the hunter-gatherer way of life — and the complications that ensued when agriculture was discovered, and more recently, from the massive disruptions that modern imperialists and market culture have inflicted.

The fate of one band of San, the Ju/’hoansi, is remarkable, writes Suzman, because the speed of their transformation “from an isolated group of closely related hunting and gathering bands to a marginalized minority struggling to survive in a rapidly changing polyglot modern state is almost without parallel in modern history.” As European settlers seized their land, forced them to give up hunting, forced them to become wage-laborers on farms, and introduced them to electricity, cars and cell phones, the Ju/’hoansi acquired “a special, if ephemeral, double perspective on the modern world – one that comes from being in one world but of another; from being part of a modern nation-state yet simultaneously excluded from full participation in it; and from having to engage with modernity with the hands and hearts of hunter-gatherers.”

In learning more about the San, then, one can learn more about the strange, unexamined norms of modern, technological society that most of us live in. It is fascinating to see the social protocols of sharing meat and food; the conspicuous modesty of successful hunters (because in the end their success is part of a collaboration); and the “demand sharing” initiated by kin and friends to ensure a more equal distribution of meat and satisfaction of basic needs.

The inner lives of the Ju/’hoansi suggests their very different view of the world. “For them,” writes Suzman, “empathy with animals was not a question of focusing on an animal’s humanlike characteristics but on assuming the whole perspective of the animal.” The performance of the hunt engenders a kind of empathy for the prey, as well as a broader understanding that the cosmos ordains certain sacred roles for all of us – as prey, hunters, and food. Hunting and eating in the Kalahari connects a person with the cosmos in quite visceral ways – something that no supermarket can begin to approach.

I’m not ready to hunt my own food, but is there some way that I can see my bodily nourishment reconnected with the Earth and my peers, and not just to packaged commodities? For now, my CSA is a good start.

The most poignant part of Affluence without Abundance is the final chapter, which describes how many San – deprived of their lands, ancestral traditions, and cultural identities – now live out dislocated lives in apartheid-founded townships that Suzman characterizes as having a “curious mix of authoritarian order and dystopian energy.” There is deep resentment among the San about the plentitude of food even as people go hungry, and anger about the inequality of wealth and concentration of political power. Most frightening of all may be the pervasive feelings of impermance and insecurity. History barely matters, and the future is defined by market-based aspirations — a job, a car, a home. The modern world has few places to carry on meaningful traditions and sacred relationships.

I was pleased to see that James Suzman has founded a group, Anthropos, to “apply anthropological methods to solving contemporary social economic and development problems.” A timely and important mission.