Part 1 of this article ended with the admonition that moderate Republicans are probably the very population cohort climate advocates should be targeting with their appeals for understanding and support. It was, I suggested, the answer to the question of why attitudinal and behavioral surveys suggesting stagnation and decline in support of efforts to combat climate change should be considered a problem by the broad community of climate advocates.

Evidence of the problem offered in Part 1 included specific references to the GMU/Yale survey responses that showed liberal/moderate Republicans in general put global warming near the bottom (21 of 23) of their policy priority lists—only 2 slots ahead of where conservatives listed it.

There was also the report of Assemblyman Mayes’ attempted evisceration by his conservative cohorts in the California Republican Party for having his picture taken with Governor Brown—well, that and having voted to extend the cap-and-trade legislation.

The situation in California was consistent with Davenport and Lipton’s characterization of the situation in Congress:

But in Republican political circles, speaking out on the issue, let alone pushing climate policy, is politically dangerous.

Through their headlines and media reports the Mason and Yale surveys, along with most others, offer more than a modicum of hope that the climate community’s combined messages are getting through to voters. Who isn’t comforted to know that despite Trump’s anti-environmental rhetoric and his administration’s efforts to rollback key protections that voter opinions are holding steady?

Since I was asked—I’m not! Already having outed myself as a glass half empty kinda guy that should come as no surprise. Part 2 continues the thought that the climate community’s message is not nearly as positively impactful as it might appear.

Cautions are in order when putting a positive spin on how in favor voters say they are of doing something to stop the world from melting like the Witch in Oz. There are underlying responses in the opinion polls suggesting otherwise.

Mark Twain wrote most people use statistics like a drunk man uses a lamppost; more for support than illumination. I realize researchers cannot control how their data is used. Advocates, however, can: control how they use information; exercise care in making statements that are not necessarily backed up in practice and/or reality; and be sensitive to how information might be received.

I remember reading two accounts of a sports competition involving the U.S. and Russia. The U.S. headline was Americans win the quarter-mile relay. The Russian read Russia comes in second in the quarter-mile relay, U.S. finishes next to last. Both were technically correct, as it was only a two-team competition. Want to manipulate the presentation a bit more?

Assume the U.S. team was the current world-record holder, then the headline might have been Russian relay team second only to the world’s fastest. There is a difference between support and illumination.

The recent spate of surveys of voter support for climate action too easily gloss over the weaknesses in the data. As regards their use in advocating pro-active clean energy and environmental policies and programs, the biggest disconnect is that constituents are not beating down the doors of their elected representatives and demanding action.

The absence of voter follow-through is particularly noticeable these days. Consider the events of the past several years. There seemingly has been a great deal more public dialogue than in the past. The science confirming global warming and its consequences has only grown stronger.

A popular president made it a core issue of his administration—particularly in his second term. Obama waxed eloquently about climate change on many occasions—occasions covered by the press. The leaders of Germany, France and the UN both before and after Trump’s election spoke often about the global warming, as have business leaders—particularly in the high-tech industry.

Pope Francis wrote an historic encyclical. The Paris Climate Accord was signed by 195 nations. It’s having been unsigned by 1 simply kept the conversation going. Hundreds of thousands of marchers carried signs in April in Capital City and throughout the country protesting Trump environmental (un)actions, i.e. undoing Obama-era regulations and executive orders.

With all of this, attitudes, according to the GMU/Yale studies and others, have not shown much appreciable change. If anything, moderate Republicans are less inclined to believe and worse—to act.

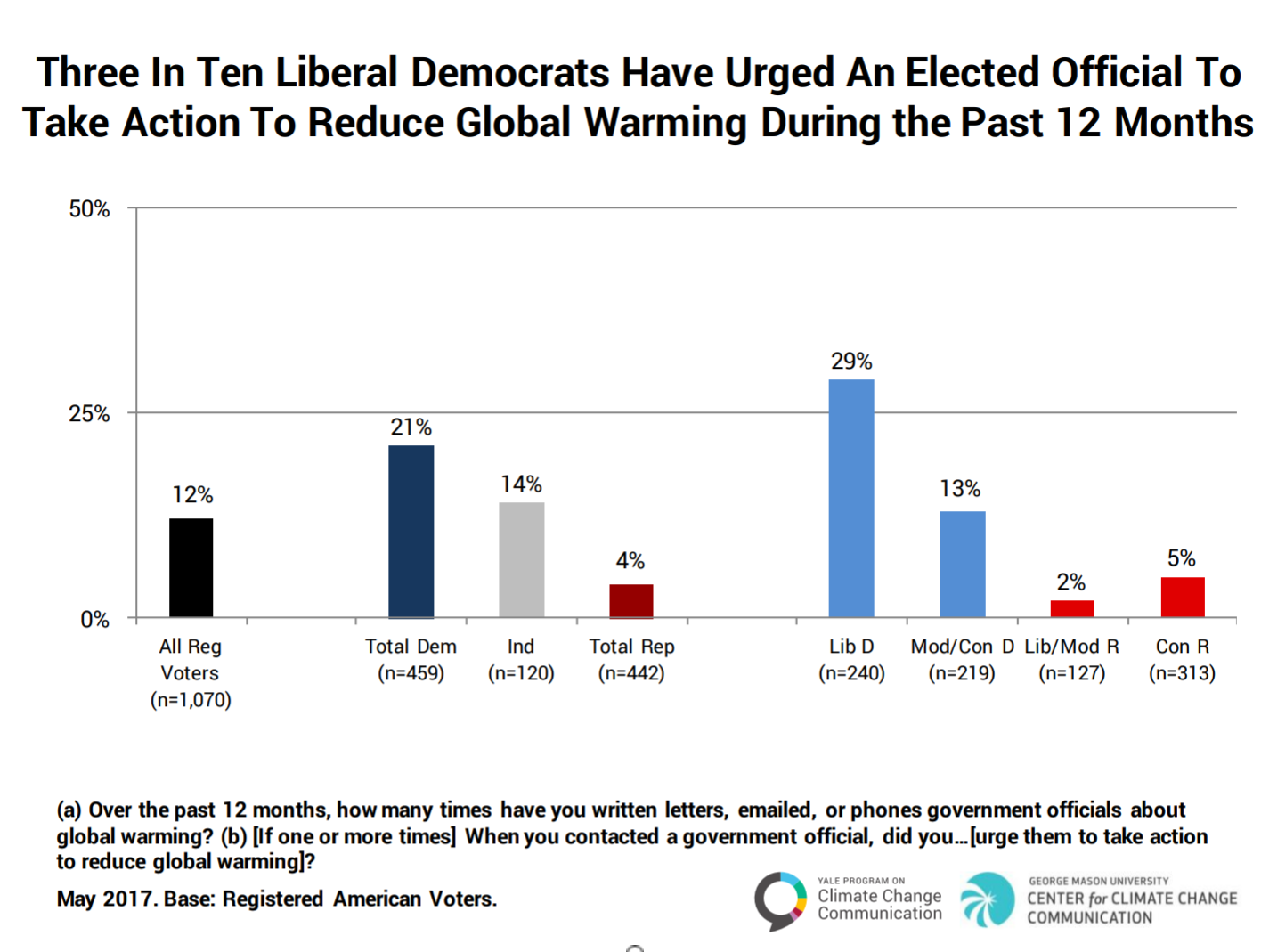

Graph 6

Most importantly, voters have not made their attitudes and demands sufficiently known to members of Congress and other elected officials. How do we know this? The same Yale/GMU surveys suggest as much.

The survey results paint a startling picture reflecting badly upon both the effectiveness of climate advocacy communications and voter attitude towards participatory government.

Only 12 percent of registered voters have urged an elected official to take action to reduce global warming in the last 12 months.

As Graph 6 shows, Democrats were much more willing, on the whole, to contact their representatives than Republicans. The number likely reflects the fact that Republicans are in control of the federal government and 32 state legislatures; Democrats, as the party out of power, are more motivated.

More willing is a relative term that in this case represents a remarkably paltry number of actual contacts–just under 3 in 10 and most of those were of the liberal variety. Only 13 percent of their more moderate/conservative Democratic cohorts bothered to weigh in with a request to do something.

Once again, the most troubling number shows up in the liberal/moderate Republican column (2%). How is it that twice as many conservative Republicans contacted their elected representatives to reduce global warming than moderates?

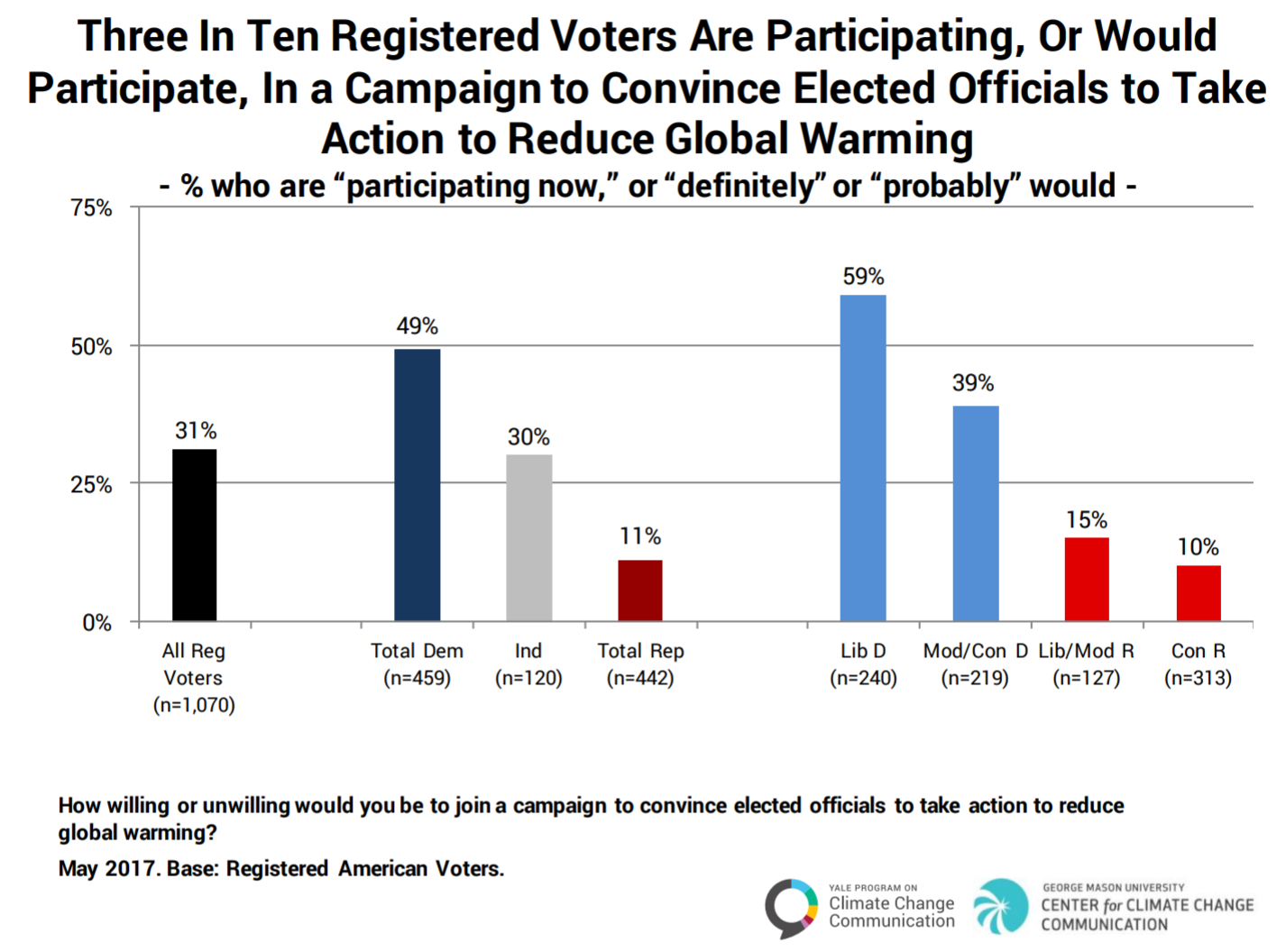

Graph 7

The pool of registered voters who are or appear willing to participate in a campaign to convince elected officials to act to reduce global warming amounted to only 31 percent of polled respondents. (Graph 7).

Consider the question wasn’t limited to voters who are participating. The question included intention. Given poll respondents are notorious for telling surveyors what they think they would want to hear–aka alternative intentions–the actual potential participation rate is likely lower.

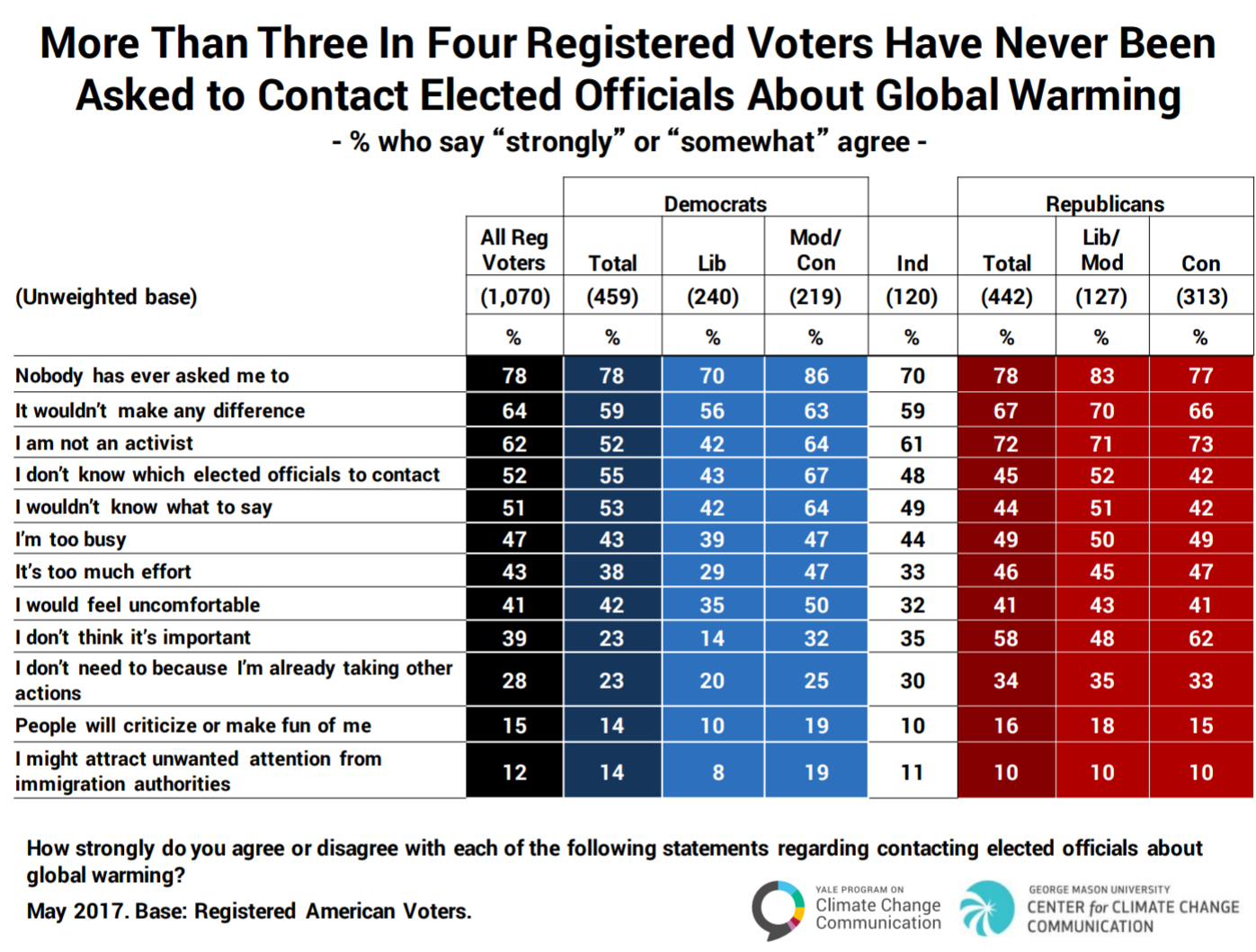

There are, of course, multiple reasons why people don’t act on their attitudes and beliefs. According to the GMU/Yale survey two of the more likely causes listed in the Table below are:

- Two in three registered voters have never been contacted by an organization working to reduce global warming. This is true across the political spectrum: 65% of Democrats, 60% of Independents, and 71% of Republicans have never been contacted.

- More than three in four registered voters (78%) say nobody has ever asked them to contact elected officials about global warming. This is true across the political spectrum: 78% of Democrats, 70% of Independents, and 78% of Republicans have never been asked

Graph 8

My personal experience is somewhat different than the survey results, as my email in-box daily fills with requests to write my Congressional representatives to encourage them to vote for or to oppose or to initiate some action or another. As a regular subscriber to various clean energy and environmental newsletters and a member of several such organizations, I doubt my experience is typical to that of the average registered voter.

Nevertheless, I am surprised by the numbers, particularly by the 78% who have never been asked. I would have assumed it was the more likely group to have voters on organizational mailing lists. Teaches me to assume. I would urge any readers affiliated with an advocacy organization in the clean energy and climate fields to review their communications programs.

Of all respondent answers the ones I find most disturbing–both from a professional and personal perspective–are the ones reflecting voter impotence and futility.

- Most registered voters say that contacting elected officials about global warming wouldn’t make any difference (64%). Only one in five registered voters (22%) think people can affect what the government does about global warming (27% of Democrats, 23% of Independents, and 17% of Republicans).

- Most registered voters say they don’t contact elected officials because they’re not an activist (62%), they don’t know which elected officials to contact (52%), or they wouldn’t know what to say (51%).

I would add to these two bullets a third:

- A majority (48%) of Americans think humans can reduce global warming, but few are optimistic that they will. Only 7% say humans can and will successfully reduce global warming. Nearly one in four (24%) say we won’t because people are unwilling to change their behavior. Only 12% of Americans say humans can’t reduce global warming, even if it is happening.

When did Americans become so defeatist? And, why? Was this a partial cause of the overwhelming expression of voter anger with established politicians exhibited in the 2016 national elections and that clearly led to the election of Donald John Trump?

If these findings are accurate, then all that can be said is the future of our nation is in a world of hurt. I don’t remember a time ever–in my life or that of the nation’s–when Americans felt hope had left the building along with Elvis.

More to the point, these sentiments are not particularly true. First, the nation has come a long way in having the tools and the knowledge to effectively reduce harmful emissions and transition to a sustainable economy.

Despite a president and members of Congress–who persist in denying the reality of the Earth’s warming and seem Hell-bent on rolling back existing protections and refusing to initiate new actions–progress continues to be made.

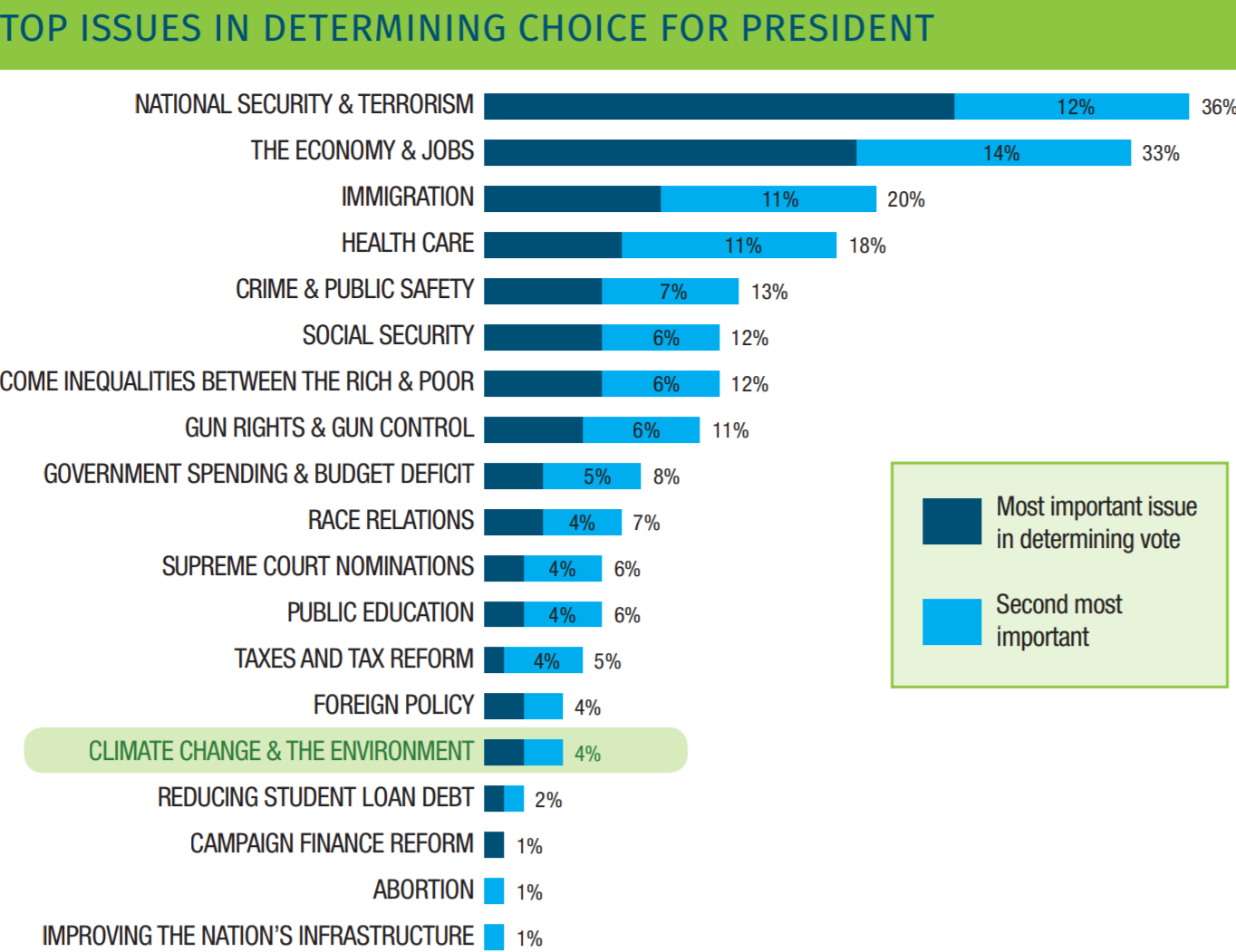

Table 2

The private sector, many state and local governments and consumers are heeding the signs and respecting the science of climate change. Unlike Trump and company, they are doing something about the problem. Is it enough? Not on its own, perhaps, but that doesn’t change having the potential to do more—much more.

As the Congress Foundation concluded:

Citizens Have More Power Than They Realize. Most of the staff surveyed said constituent visits to the Washington office (97%) and to the district/state office (94%) have ‘some’ or ‘a lot’ of influence on an undecided Member, more than any other influence group or strategy. When asked about strategies directed to their offices back home, staffers said questions at town hall meetings (87%) and letters to the editor (80%) have ‘some’ or ‘a lot’ of influence.

There were nearly 16 million environmentalists who DID NOT vote in the last presidential election, according to the Environmental Voter Project (EVP). The organization’s research found a participation rate of only 50 percent of eligible environmental voters the 2016; a dismal turnout number even by U.S. standards.

Overall 55.7 percent of eligible voters cast ballots last November. Think what the 16 million no-show avowed environmentalists would have meant. EVP also lists climate change and the environment far down the list of 2016 voter priorities (see Table 2 above) . The finding supports the results of the GMU/Yale reports.

Even a committed card-carrying curmudgeon has hope that the future will be brighter than the past or the present. More than hope, I have confidence. After all, it’s not that I see an empty glass.

Success is not a matter of wishing, however—if it were, beggars would be kings and I would be handsome and rich. Experience and the findings of attitudinal and behavioral research suggests increasing active voter participation requires a better understanding of how people receive, consider and interpret information.

Click into the next installment of this series, when I examine the growing body of evidence suggesting people no longer relate to experts and their data as they have done in the past. It would help to explain the rising accusations of FAKE NEWS and the growing willingness of voters to believe ALTERNATIVE FACTS.

It is the consequence, according to Isaac Asimov, of a thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means…my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge.

I guess we’ll just have to see about that won’t we?

Source : Table 2 Top Issues In Determining Choice For President/Environmental Voter Project

Teaser photo credit from People’s Climate March: https://peoplesclimate.org