The heat of the summer is not just a nuisance but a significant public health threat. In most years, extreme heat causes more deaths than any other type of weather-related disaster. The danger is most acute for elderly people, who are more vulnerable to the effects of heat, and for people living in low-income areas, where cost barriers and features of the built environment make it harder to stay cool in hot weather.

Urban heat islands trap heat, making neighborhoods like this one in Washington, D.C., even hotter on sizzling summer days. Photo by AgnosticPreachersKid, Wikimedia Commons.

As the mercury rises, temperatures vary substantially on the basis of proximity to trees or water, the density and nature of built structures, the heat output of air conditioners, and many other factors. Heat mapping is an innovative, data-driven method to visualize temperatures across a geographic area in order to understand why some areas get hotter than others on summer days.

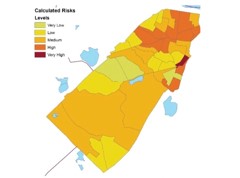

By layering temperature data with demographic and socioeconomic information, heat maps can reveal the drivers that create risk spikes within a city. Three TEX projects are using heat mapping to help cities address different types of heat challenges.

“Many cities are interested in including extreme heat mitigation in their climate adaptation plans,” says Juan Declet-Barreto of the Union of Concerned Scientists and a scientific partner for a TEX project in Washington, D.C. “Detailed information on the people and places most sensitive to extreme heat can help prioritize resources, turning scientific data into straightforward, actionable information to help.”

The nation’s capital is essentially one enormous heat island, where the built environment causes temperatures to rise several degrees compared to the more forested areas just outside the city. It’s also a place where large low-income neighborhoods create pockets of heightened vulnerability to the health risks of extreme heat.

“These public health burdens cannot be overemphasized,” says Declet-Barreto. “We now know that across the world, vulnerability to extreme heat is mediated by socioeconomic status. Small-scale mapping helps us understand these inequities.”

Many underestimate the dangers of extreme heat, which causes more deaths than any other type of extreme weather. U.S. Air Force photo by Sue Sapp.

A TEX project in Brookline, Mass., also combined information about urban heat islands with demographic data. That exercise identified the elderly as a particularly vulnerable population within the city. The collaboration informed decisions about mitigation strategies such as increasing tree cover and designing cooling centers to give elderly residents a place of refuge on the hottest days.

The threat of extreme heat even reaches into historically chillier areas, such as Missoula, Mont. In addition to acute health threats of extreme heat, rising summer temperatures can wreak economic havoc by reducing tourism and increasing residents’ energy use and costs. In a new TEX project in Missoula, Mont., scientists and community members are working together to create heat maps and address priority areas for interventions such as urban forests.

Heat maps like this one of Brookline, Mass., help city officials identify vulnerable populations and prioritize mitigation strategies.

“We are just in the beginning stages,” notes Chase Jones, City of Missoula energy conservation and climate action coordinator, “but we believe this data will inform and enhance our growth policy, building codes, infrastructure plans and urban forest management.” The project extends and enhances Missoula’s Summer Smart program, a project to prepare community members for increased heat and wildfires in summer. The challenges associated with rising temperatures may be a little different in each place, but experience shows that heat mapping is a technique that can prove useful in almost any scenario.

“If you have the opportunity to inform policy and improve your community’s quality of life with science and data, jump on the opportunity,” Jones urges. “Unprecedented heat due to climate change is not going away, and preparing our communities to survive and thrive is something that shouldn’t wait.”

Explore our projects in Washington, D.C., Brookline, Mass., and Missoula, Mont.

Teaser photo credit: Green roof of City Hall in Chicago, Illinois.. By TonyTheTiger, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5236408